Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowOlives and His Mother Were the Only Things He Loved

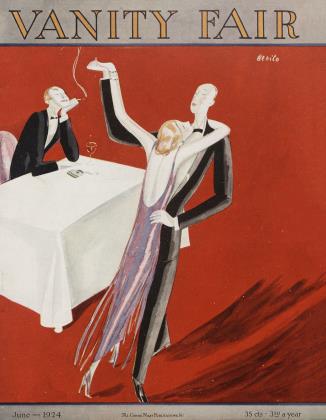

A Little Glimpse of Life in the More Rarefied Regions of New York Society

CHARLES G. SHAW

MR. BERTRAM WINSTON CARBURY was one of those youthful and exquisite ornaments who grace the uppermost reaches of society in New York. His discreet Sunday afternoon cocktail gatherings, his exquisitely-served suppers in his Park Avenue apartment, and his enticing luncheons at the Piping Rock Club conspired to make him an object of singular favour along the more fashionable stretches of Fifth Avenue.

It resulted, inevitably, that Mr. Carbury was besieged with invitations to dinner—invitations which he pondered—and accepted. Moreover, being (legally) unattached, he accepted all of them. Where, when, or why made not the slightest difference to him: he invariably R. S. V. P'd. in the affirmative, but subsequently crawled out of the less attractive ones by wire. Indeed, young Carbury was famous for the deftness of these last-minute retreats; and hostesses had been known, for months afterward, to cherish fondly his charmingly worded telegrams of withdrawal.

Thus, on a certain hazy evening, during the middle of the season, he discovered, with some consternation, that he had made three different engagements for dinner. Cursed oversight! He had completely forgotten to chuck two of them I Three different dinners for a single evening! What was he to do? In his entire social career, he had never been known to disappoint a hostess—except, of course, by wire—and he swore by all the Corona Coronas he might ever hope to smoke that he would cause none of his hostesses the slightest embarrassment or chagrin. His reputation as a modern Chesterfield was at stake.

MRS. STUYVESANT HARBOROUGH-S dinner was the first of the lot—a half-pastseven event—and Mrs. Harborough so disliked having her guests arrive late. "Not that it matters about the food," she would murmur plaintively, "but the cocktails get so dreadfully warm." Carbury had accepted her invitations for the past five years; but, in all that time, had successfully avoided dancing with Estelle, her soul-blighting daughter.

The next feature on the program was the Tankersmythes'—the Ogden Lennox Tankersmythes'. This function was scheduled for eight o'clock, but some one was always late at the Tankersmythes'—usually one of those terrible Stevenson girls, whose excuses were about as transparent as a Palm Beach bathing suit. Finally, and fortunately, at eight-thirty, came the John Saltonstall Featheringays', certain to be the choicest dinner of the three, from the point of view of company, cuisine, and champagne. "Of course,.there's far too much drinking in these days of Prohibition," Grace Featheringay had so often said, "but who can have the slightest respect for the type of man that is invariably blind sober? My own experience", she would add, "has taught me that the biggest bore in the world is invariably the reformed drunkard."

The three hostesses, Bertie Carbury suddenly recalled, all lived within a few blocks of each other—which simplified matters enormously— andalookof Machiavellian cunning,overspread the young man's usually placid countenance.

As he whistled a popular catch, he gave the finishing touch to his tie—the fifth of his attempts at perfection—and turned away from the mirror. To feel out-of-sorts, he reflected, was an injury to one's self. To look out-ofsorts, an insult to one's friends. Then, glancing at Catchpole, his valet, he misquoted W. S. Gilbert, somewhat enigmatically: "For olives and his mother were the only things he loved". The other, thoroughly accustomed to the idiosyncrasies of his "gentleman", stared impassively at his retreating and sprightly back.

There was a tinkling, metallic click, as a diminutive Louis Seize clock in the Harborough mauve drawing room sounded the half-hour. At precisely the same moment, Carbury, smiling pleasantly, was ushered in and bowed profoundly to the statuesque and rather frigid Mrs. Harborough—nee Bonnie La Salle, of Oil City.

"I'm afraid I'm a trifle early," he apologized, "but, you see, 1 walked instead of taking a taxi."

The other guests soon began to arrive; and, after a delightful conversation about the Gordon Joscelyns' divorce, every one trooped in to dinner. "The number of divorces, nowadays," explained Freddie Spottsford, a plump, floridfaced youth, "is entirely due to the number of marriages."

"Do you know, Mr. Carbury," confided the ecstatic and blonde young lady on his left with the heavily-reinforced eyelashes, who was quite as beautiful as a sunset and twice as obvious, "I see you almost everywhere I go." Then she added nervously, choosing from her conversational repertoire at random, "What do you think of the oil scandal ?"

Carbury smiled at her reassuringly and helped himself to an olive.

"The really amazing thing about the politicians, both in Washington and abroad," he was oracularly telling his fair neighbour, "is that neither the party in power, nor—"

But he got no further, for an acute fit of coughing suddenly overcame him, and he clutched at his throat in agony. He must see Dr. Foster—Dr. Sackville Foster—at once! He must leave Mrs. Harborough's: he had swallowed an olive! He was extremely sorry, but surely his hostess would understand. Then, frantically waving away the gracious offer of a motor, the young man left the house.

Just around the comer, he hailed a passing cab and directed the driver to proceed to the Park Avenue entrance of the Ogden Tankersmythes', recently remodeled by the most fashionable and impersonal of French decorators. The cool night air had a tang of Cordon Rouge in it, and the young fellow drank it down in great, refreshing gulps. The spice of adventure coursed through his veins.

"TT'S awfully nice seeing you again, Mr. Carbury. You haven't changed a bit, except that you look so much better." And the radiant Mrs. Tankersmythe smiled ever so sweetly. Mrs. Tankersmythe had formerly lived in Jersey City, but since her marriage to the richest ofthe Tankersmythes had, with the aid of Vogue's Book of Etiquette> partially succeeded in concealing the fact.

"Do have a cocktail or two", she beamed, "before we go to dinner."

Once at the table, Carbury found himself seated getween a pale young woman with shingled hair and an over-rouged brunette with an Egyptian coiffure. He sniffed suspiciously. Both used Caresse d'Amour. Of the two, he chose the brunette. He also chose an olive.

"I wish you could tell me, Mr. Carbury," the brunette implored, "why I never seem to win at Mah Jong."

"You do not win at Mah Jong", replied Carbury, with the poise and assurance of a professor of the new psychology, "for the reason that, as Matthew Arnold once observed, 'Your nature, though timorous, yet leaps at—' "

But the rest of the quotation was lost, for again the young man choked and coughed and clutched at his throat.

"Poor Mr. Carbury! You have swallowed an olive! How horrible! Of course you must see the doctor about it. I do so hope it isn't serious."

Mrs. Tankersmythe was such a sympathetic woman.

CARBURY reached the Featheringays' on the stroke of eight-thirty. The cocktails, he rejoiced to note, contained just the proper amount of absinthe. Moreover, they arrived in three rounds.

"You're at the other end, sir." And Quinlan, the butler (imported from England—Heaven only knows why), consulted an elaboratelyembellished diagram which indicated the seating arrangements of the dinner. Everything the Featheringays did was thoroughly elaborate, from the platinum-lined swimming pool in their house at Roslyn to the electrical jazzorchestra in their little palace in the Adirondacks. Furthermore, they were always up-tothe-minute in their tastes, implicitly believing in the celebrated adage, "Nothing grows passe so quickly as modernity."

It was a party of twenty, and every one seemed in excellent spirits. They had not seen one another since the night before; and, brightest news of all, Mr. Featheringay, the host (one of those red. noisy men, who had often been reported for sleeping on the billiard table at the Links Club), had failed to return from Aiken, whither he had ostensibly gone to improve his game of bridge, but really to put a razor edge on his thirst. All in all, the evening looked distinctly promising.

Continued on page 96

Continued from page 40

Carbury sighed a well-bred sigh of contentment. At last, his cares for the evening were over. His strategy had worked to perfection. He felt singularly on the crest—a condition to which the cocktails had certainly contributed their share. How he glowed at the prospect of the delicacies in store for lnm! Caviar d'Astrakhan, he detected on the gilt menu, and filet of pompano a la Reine. Then, there was a ruddy duck, and a mousse with marrons glaces, and a savory a la Sevigne!

THE divinity on his left seemed to him the most enchanting creature he had beheld in ever so many seasons —the quintessence of mystery and charm, and bedecked in one of Vionnet's flimsiest creations, dripping with little things from Cartier's. Her eyes shone like the brass buttons on the taxi starter at the Ritz, and her rosebud mouth was quite as realistic as anything in Thorley's window, and quite as charming.

Of equally prepossessing mien was the young lady on his right, a perfect copy of one of the sirens in Senor Sert's arresting murals. With half-shut eyes, the siren gazed at Carbury, who, smiling serenely to himself, selected an olive from the golden bowl before him. "Yes," he reflected calmly, "the Chateau Latour is just the right temperature."

About the table floated the lightest sort of chatter—chatter that touched upon every one in their little group w-ho in any way was involved in a scandal. Carbury began to wonder which of his famous anecdotes he might venture first—whether to risk the rather lengthy one about the indecorous coloured lady, or that highly droll little conundrum with the answer in French.

As he opened his lips to give vent to tire conundrum, a strange commotion arose at the table: a murmur of distress ran around the room. What had happened? No one could possibly imagine.

Finally, the distress was localized. It came from Mr. Carbury's end of the table. Then, dazed, shaken, and choking immoderately, our hero gasped out an agonized phrase. He must hasten to Dr. Foster's, Dr. Sackville Poster's, immediately. He was desperately ill. He might even be dying!

This time Mr. Carbury actually had swallowed an olive!

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now