Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowArt and Life

In Which it is Contended that Life Frequently Goes To School To Art

ALDOUS HUXLEY

EVERY now and then there appears on my breakfast table an envelope addressed to me, care of my publishers, in an unknown handwriting. I open it and find that it contains a letter from some unknown admirer or detestcr of my works—generally the former (for the haters don't take the trouble to write, preferring not to soil their note paper with an epistle addressed to such a monster as myself) and generally, also, from admirers of the female sex. I read these letters with interest; and my ardent fancy conjures up the most ravishing visions of their writers. I imagine them very young, brilliantly clever and exquisitely beautiful. But sober reason intervenes, quoting to my overheated fancy that terrible saying of the painter Degas, who, when reproached by a lady for always making the women in his pictures look so ugly replied: "Mais, madame, les femmes en general sont laides." Not very gallant, but alas, too true. My imagination cools and I put the letter aside, to be answered in a brief and business-like manner when occasion offers.

YEARS ago, at the very beginning of my literary career, when I was writing impassioned love poems to nobody, I should have responded to such letters, if l had ever received them, in a very different, a much more tender, rapturous and romantic style. At that time it was the height of my ambition to write works which should provoke correspondence with the feminine readers of them. It seemed to me, then, that nobody was more to be envied than the writer who receives letters from lady admirers and who answers them in long letters of his own, full of an intellectual and idealistic sensuality. My views are a little different now. Correspondence with fair strangers seems to me less desirable, if only because correspondence generally leads, in the long run, to personal meetings. Tschaikovsky, it is true, managed to keep up a correspondence for twenty years with a rich admirer, whom he never saw, and who made him a handsome cash allowance; that was an ideal state of affairs. But it is difficult, generally, not to meet one's correspondents. Balzac's case is a terrible example. Ladies were constantly writing to him; and he, with that ardent and romantic boyishness which went hand in hand with his rather cynical knowingness, responded enthusiastically. The result was that he was always engaged in the most tiresome love affairs. The last of these-correspondence-affairs with female strangers was the death of him. After years of letter writing he actually married the romantic countess who had written to him years before from her palace in Little Russia. A few months later he was dead. The moral of that is: don't enter into entangling alliances, even at long range. Forewarned by his fate, I make my answers to such letters as brief and as formal as courtesy will permit.

Some little while ago I received a particularly engaging letter—so engaging that I was tempted to throw discretion to the winds, to forget the fate of Balzac and the embittered wisdom of the painter of women, and reply in nineteen sheets of tender, wise and witty badinerie in the style of the letters of Alfred dc Musset to Aimee d'Alton. In the end, however, reason prevailed and I did nothing of the kind. But the letter continued to preoccupy me. There were one or two sentences in it that made me pensive. For the writer had remarked, among other things, that my works had had a profound influence on her life and that she was firmly intending to put my "charming principles" into practice. Now, what she imagined my principles to be, and why she should have thought them charming, 1 do not know. My principles, as a matter of fact, happen to be identical with those of St. Augustine; but 1 could not help feeling that the authoress of the letter had made some mistake and was anxious to put my principles into practice because she imagined them to be something very different from what in reality they are. Not that I minded being misunderstood; indeed, it would be horrible and humiliating to think that one had been perfectly comprehended. But 1 was somewhat oppressed by the thought, which had never occurred to me before, that 1 might be exercising an influence over anyone in any direction. To have to be in any way responsible for other people, when one can hardly assume responsibility for oneself, is dreadful. That letter disquieted me and made me pensive. In the future, I felt, I should be well advised to preface my books with a little notice, similar to that which Galileo appended to his astronomical writings, to the effect that whatever I say must be taken merely as a mathematical hypothesis and must not be held to commit the writer, or allowed to influence the reader, in any way.

FROM my own case, which is after all an exceedingly trivial and unimportant one, I went on to consider the case of other artists and of the influence which art in general has exercised and still exercises on life. Many laborious and boring critics have devoted all their deplorable energies to investigating the influence on art of surrounding life. Few have considered the opposite tendency—the reactions of art on contemporary life; and none, so far as I know, at length or systematically. And yet the subject, when one comes to think of it, is exceedingly interesting. For the effects that artists have had on the life around them have often been considerable and in the greater number of cases of a rather curious character, tending towards the creation in society of extreme and exaggerated types.

The effect produced by an artist on his contemporaries is not at all proportional to his intrinsic merit as an artist. Many of the greatest artists, indeed, have exercised little or no influence on the habits of their contemporaries, while men whom we now see to have been mere charlatans and mountebanks, have enormously affected the social life around them. Shakespeare, for example, had no direct influence on social life in the reigns of Elizabeth and James I—nor, for that matter, on life at any subsequent period. He has no particular 'principles', such as my young correspondent discovers in my writings. He did not discuss ideas that were fashionable at the moment or emphasize one particular human tendency at the expense of the rest. He was universal and of all time. Hence he created no special social tendency. Oscar Wilde, on the other hand, who was a specialist artist, insisting oh one side of life and having peculiar 'principles', had a profound effect on the social life of his age. With Beardsley, he invented decadence as a social stunt. Society during the last years of Victoria's reign would have been different if Wilde and Beardsley had never lived. Shakespeare on the contrary inaugurated no stunt, and Elizabethan life would have gone on just the same if he had never existed. The social effects of Marlowe and of Donne were very much greater than were those of Shakespeare.

To enumerate all the artists who have exercised a direct influence on the social life of their contemporaries would be tedious. Vast erudition and unlimited space would be required in order to do the job properly; and I possess neither. I shall confine myself to giving a few fairly obvious instances from the past and from contemporary history.

OF all the great artists who have had a social influence, none, 1 imagine, can have had a greater influence than Byron. He popularized world-weariness, made romantic misanthropy fashionable, created a vogue in diabolism. The number of young men who, in the early years of the last century, were turned, for a shorter or longer period, into insupportable young cubs under the direct influence of Lord Byron's poetry must have been enormous. Fortunately for the young cubs, he also created a large audience of young ladies all ready to regard the aforesaid Y. C.'s as the last word in romantic attractiveness.

Among the great French writers who have had a similar social effect we may mention Balzac. The fact which I have already mentioned—that he was the recipient of a copious correspondence from female strangers—might have led us to guess as much. But we have it on the direct authority of Saintc-Bcuvc that there were cliques in the most fashionable Parisian society which deliberately took the parts of Balzac's heroes and heroines and acted them in real life. The effects must have been most interesting, seeing that Balzac's characters are always extreme types, whether of vice or virtue, ingenuousness or cynicism, and almost monomaniacal in the fixity and unity of their several purposes.

Of the world's absolutely first class and universal writers, none have had so much influence, during their own time and in subsequent years, as Dostoevsky. The effect of 'The Brothers Karamasov' and 'The Possessed', especially on adolescents, is generally of a somewhat disastrous nature. Much violence, many quite supererogatory beastlinesses and unnecessary suicides of young people have been due to Dostoevsky. The fault lies less in the writer than in his readers, who failing to understand the inwardness of his method, have tried to put his books literally into practice. Just as in the laboratory the chemists discover the intimate secrets of matter by submitting it to extreme heats and colds, to chemical disintegration and recombination, so Dostoevsky examines the intimate constitution of the human soul by putting his characters into situations that test them as severely as matter is tested in a furnace. What he discovers is extraordinary. No man has ever seen further. But it is not necessary to repeat laboratory experiments in real life.

(Contmued on page 82)

(Continued from page 35)

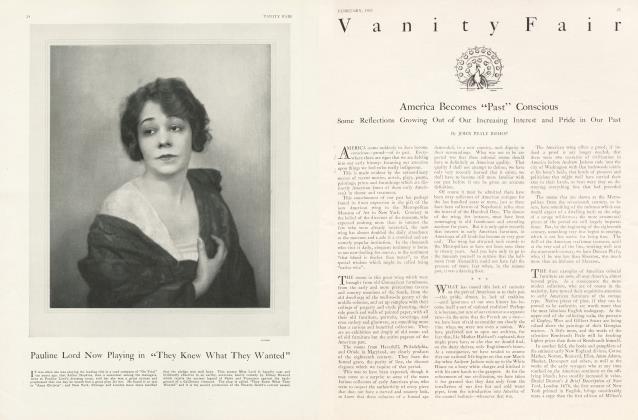

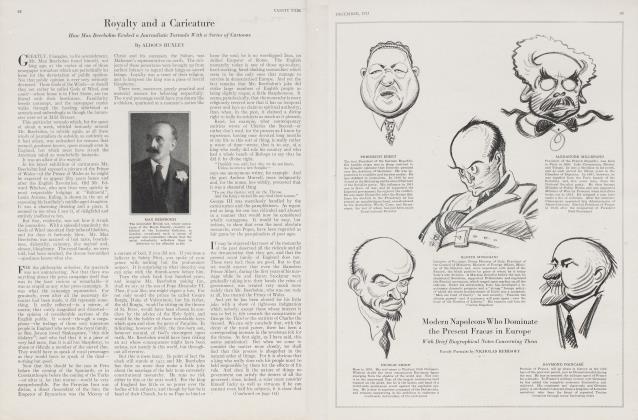

Painters and draughtsmen have had their influence as well as writers. It is the painters and, above all, the popular draughtsmen who determine the fashionable style of beauty at any given period. The egg-faced, smooth-tressed, champagne-bottle-shouldered young lady of early Victorian times is the invention of artists such as Etty and of a host of fashion-plate draughtsmen and illustrators. Du Maurier was influential in creating that type of classical and queenly beauty popular in England during the eighties. All the photographs of society beauties belonging to that period conform to the type he created. What happened then to the snub-faced young women who have been popular of more recent years I do not know. Du Maurier condemned them to outer darkness. In the early twentieth century we had the Gibson girl, who degenerated into the pretty little shop girl type of the fashion plate. This type has remained popular till quite recently, when a new type has been imported from France. Its inventor is Marie Laurencin. The draughtsmen of Vogue have popularized it out of France. Marie Laurencin, moreover, is responsible for that wave of imitation manliness which is somewhat perversely invading female fashions at the present time. Her delicate little Amazons may be seen, translated into flesh and blood, in the streets of Paris, London and New York.

Another contemporary artist who has been immensely influential, in England at any rate, is Augustus John. His influence was at its height some years ago, when he positively called into being the young woman from Chelsea. Mr. John is a most admirable painter; but he is also responsible for short hair, brilliantly coloured jumpers, a certain floppiness and untidiness and a deplorable tendency to pose against cosmic backgrounds on the top of hills or by the sea. The "arty" young lady, who was once a living Rossetti, is now a John.

On cultured society no contemporary writer has had a more penetrating effect than Marcel Proust. Since the publication of A la recherche du Temps perdu love is made, in the best drawing rooms, in a new and Proustian fashion. His interminable analyses of the passion have enabled somewhat jaded young men and women to love once more at greater length, more self-consciously and with a more damning knowledge of what is going on in their partner's mind than was possible in the past. Without such occasional renewings, love tends to become rather stale in those sections of society where it is the staple occupation. Writers like Proust are real benefactors to humanity, or at any rate to certain sections of it. Another great renewer of love is Mr. D. H. Lawrence, who, magnificent writer though he is, is responsible for much in certain sections of contemporary society that is exceedingly tiresome. It is certainly true that one can have a great deal too much of love and hate, loins and solar plexuses.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now