Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

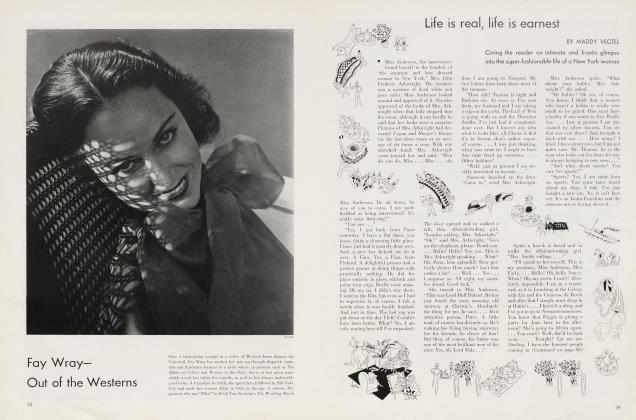

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowBetween Eight and Nine

In Which a Lovely Dutch Actress Discovers That She Is Not Really in Love

MADDY VEGTEL

NINI PENN, the actress, exclaimed: "How delightful!" as she stood in front of the open window and saw the slate-blue waves of the Channel not more than ten or fifteen yards away from her, and just beneath her a narrow strip of boulevard.

She turned to the waiter who had brought in her luggage and who was now on the point of leaving the room. "I want to have a note delivered at the Hotel Beau Séjour," she said. "Will you send someone up in about an hour—"

Alone, she started to hum, then to sing softly: Malbrough s'en va-t-en guerre, and louder: Ne sail quand reviendra—ne salt quand reviendra. She felt very happy and was conscious that her heart was beating loudly and that her hands trembled. She went over to the wash-stand to take a drink but there was no water either in the jug or in the pitcher. Nor was there any rug or mat on the painted wood floor.

Oh well! what did it matter! Nini considered herself lucky to get a room at all in midsummer without reserving one in advance.

For only that morning she had packed her suitcases in a frantic hurry to catch the train which left The Hague at 7:25. It was 5 o'clock now and very warm. She unpacked, took off her dress and her jewelry; undid her Fair, which she wore parted in the middle with a plait twisted round each ear, and lay down on the bed, her arms folded under her head. She looked at her legs admiringly, then at her hands, spreading the fingers wide apart, finally she took up a mirror and gazed at her reflected image.

WHEN the waiter came to fetch the note she gave it to him saying: "There will probably be an answer—"

What would it be, the answer? Her thoughts returned to what she had written: "Dear Tony, Imagine my surprise when I heard you were staying here—Could you come to see me this evening: I would love to see you again. I have not seen you in so long."—It was wonderful! After so many years, ten to be exact, ten years last June—and now she would see him. Even at this moment, probably not more than an hour's distance between them—What would the answer be? My dearest Nini, I will come to fetch you—Nini darling, you must come and dine with me—Nini, how delightful —What should she wear—did people dress here? Probably not. The place wasn't fashionable—, she would wear her white chiffon dress and pin the pink velvet gardenias on her shoulder—Ten years ago she had worn a dress with a short little bodice and a pattern of blue and mauve flowers sprinkled over the paniers, and she had worn a leghorn hat. In those days, she was the ideal jeune fille, fair, slim, fresh, with an oval face tinted in the palest pastel shades—her beauty had never really been striking till she had started to spend extravagant amounts of money for clothes. Her face and her figure both were easily adaptable to every whim of fashion.

Ten years ago. She remembered well! They had driven to Scheveningen in the evening—Nini, and her father. She had driven the governess-cart and had taken the route through the Scheveningschezveg., the avenue through the woods leading from The Hague to the sea. In Scheveningen they had gone to the Kurhaus-konzert and someone—was it Brigit Engel or Onegin—had sung: Es ist bestimmt im Gottes Will', dass teas sich am liebsten hat auj Erd, muss scheiden—Afterwards they had met Tony and with him and others they had gone to the Rotonde—how wonderful it had been—that warm clear night, the dark blue sky, crowded with stars, the calm dark sea and the smell of the red roses which Tony had bought for her—and the gay people around her. And while she was looking at the sky, at the sea, at the people, she was conscious that Tony's eyes were fixed upon her—They were engaged, but no one knew but themselves. A week later the Standard Oil Company (Tony worked for it) transferred him to Singapore.

SHE had cried, telling her father between sobs, that if he did not allow her to marry immediately she would die. Then, months later, Tony had written that the company would not allow him to marry for three years at least and he thought it best to break the engagement. She had heard of him later through others,—heard he was doing well. He had left Singapore for Padang in Sumatra, he had gone to Java, he was living in Soerabaya— finally she heard Tony had married, never that he had returned to Europe.

And Nini, in Holland, lived a life of varying success. She became an actress, she became en vogue, she impersonated alternately the Paulas, Mizzis, Dollys and Ninas of Pinero, Jones, Molnar, and Schnitzler, but her own life was lived in dreams, heureux mais un feu triste: in dreams of dazzling white Javanese fields, of Sumatran hills, of Dutch-Javanese houses. Always she saw herself beside the man she loved, not, (if she had but known it) Tony, but a mere image which many years of absence had made her imagine Tony to be.

Hers was no mere love that depended on touch, sight or possession. A year ago she had cared for someone else, in fact become engaged. Then she had wished that Tony's image would not obtrude itself so persistently between her and the other man. The engagement was finally broken.

And now the day before yesterday a friend had told her that he had met Tony at a small French seaside resort—

Nini, in a frantic hurry, went to the resort: it was silly to talk about pride—after ten years. . . .

II

She saw him first as she passed through the café. At the moment a clock struck eight, she saw him sitting with his back turned toward her. He was wearing a grey suit and on the chair next to his lay a white straw hat, a pair of gloves and a walking stick. When she approached, he suddenly turned around, jumped up and stretched out both hands.

The thought rose to Nini's mind: he has changed! Meanwhile Tony was babbling on: how well you look—how are you—shall we sit down or take a little walk first? Let's walk, she answered. He took up his hat, his gloves, his walking stick and asked her which way they should go. She answered, left and they turned in the direction of the lighthouse . . .

For a minute or two neither of them spoke. Finally Tony asked: "Have you been here long?"

"Oh no!—that is, just a few days—" Why had she said that? why not the truth: I only came this afternoon.

"It was wonderful of you to have sent me that note—I never expected you would remember me—"

The moment had come for her to say: I loved you, and I still love you . . . but the words remained unspoken.

Somehow it was so different from what she had expected. She had half expected, that he would take her in his arms—in front of the hotel, and cry out: "At last!"

She glanced up at him, sideways; he was handsome but stern, his blond face looked as if it were a wood-cut portrait—the eves seemed to be narrow slits—

SUDDENLY he looked at her, and to the question "Are you married?" replied: "No —I was, but my wife died not long ago—No children! You didn't know that? I thought you knew."

"Why should I," thought Nini. "Why is he so sure I am not married? I could have married if I had wanted to—"

"I am now at the Batavian branch, they are sending me out to America soon. I travel a lot—and you—you still live with your father, I suppose?"

Nini felt a sudden wave of anger, her cheeks flushed—He pitied her, that was it— did he dare think that she had sat home all these years waiting for him, that she had not married because of him, that she had grieved all these years because he had left her! It was unbelievable, why the newspapers devoted columns to her after the fremiere of Amoureuse, there had never been a Germaine like her before, they had said, and Schnitzler himself after—and Echague had painted her, and Van Dongcn, and the girls in Holland imitated her speech, her demarche—and now he presumed—it was unheard of!

"Perhaps," she said, her voice a trifle unsteady, "if you go to Holland you'll hear about me—I am quite well known there—in fact, I am their best-known actress—"

"Oh!" his voice sounded surprised,—"how wonderful—I have little time for books and theatres and that sort of thing—I am a very busy man—I have several sugar plantations in Sumatra and, of course, they need looking after and—" His voice went on, but Nini suddenly became aware of their surroundings. It was nearly dark and the Boulevard deserted, the Channel was rapidly rolling on towards England, leaving behind it a large expanse of beach— a little gust of wind suddenly made her shiver. Why on earth had she put on that thin white dressr If she only had her coat—or her blue-and-white shawl—next time she was in Paris she was going to buy a black one, one with—

(Continued on page 100)

(Continued from page 74)

But just then Tony interrupted: "Do you intend to stay here long?" he asked—"Perhaps we could go back to Holland together—via Brussels—" He was looking at her intently now, his eyes went over her face, over her body—

"Let's turn back," Nini said. She ignored his question, and walked on silently, her lips trembling with anger—

How did he dare, what did he think, she had been a fool to write that note—what had possessed her to write it—

It was quite dark now. Behind them was the lighthouse.

Tony took her arm, "Come, let's go to my hotel and drink something to warm us up—"

"I am tired—"

"Oh—come—!" he was trying to persuade her.

"No", she replied somewhat curtly.

They walked back in silence. In front of her hotel they said goodbye. He held his hat, stick and gloves in one hand, the other clasped hers. "But tomorrow," he said, "tomorrow I'll fetch you at eleven—no, I have to see someone at that time, twelve, I'll fetch you at twelve—we have so much to talk about"—"Yes", she said. A "good-night" and she was gone, leaving him standing there, smiling, his eyes half closed, thinking of a decidedly agreeable future.

III

The train rushed through France, Belgium and back to Holland. It was 3 o'clock in the morning,—not more than six hours since she had left Tony standing in front of the hotel. Nini Penn, alone in a dark compartment, sat up, her hands folded around her knees, a checked blanket thrown over her shoulders.

"Tony," she thought, "I have seen Tony." It had really come about and now—he was nothing to her anymore. She simply did not love him. That feeling, a trifle sad but unutterably sweet, was gone, and forever— she could love again and when she did, it would be like ncver-having-lovedbefore. Tony's image would no longer come between her and any other man. It was strange but wonderful—

But was it? Being free of that love. And she wondered if she could ever experience such happiness in loving another man as she had experienced in loving the Tony who had really never existed . . .

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now