Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

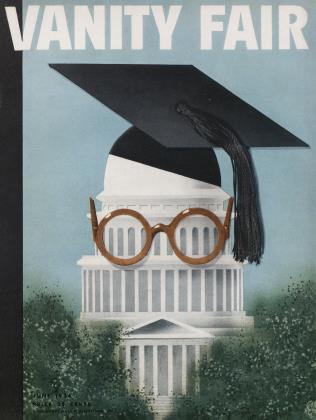

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowBlonde Venus and Swedish Sphinx

MADDY VEGTEL

Marlene Dietrich and Greta Garbo, who, to the wondering eyes of the American public, epitomize the glamor of Sin

Culture, for the American masses, seems to he dealt out by the movies. People who, a year or two ago, had never even heard of, let us say, pygmies, have now seen and heard them on the screen. So it goes with other things—facts and emotions alike. And, among the emotions, love, of course, stands foremost.

For many years the American public has known that the European understanding of "love" differs slightly from their own conception of it. But in exactly what respects, they hardly knew.

Today, this love (usually illicit and, for centuries, the basis of most European drama and literature) is being pictured to the delight of thousands of American movie-goers. And who are the chief exponents of this emotion? Garbo and Dietrich.

Garbo and Dietrich are hailed everywhere in this country by an enthusiastic public who sees in them and in their plays (for the most part, threadbare clichés) all the romance, glamor and excitement of forbidden passion. But I wonder if this public realizes exactly what it really is that the) are applauding with such enthusiasm?

■ Recently, in an advertisement of Little Women, I was surprised to see that compound of cotton snow flakes, lace pantalettes and gingham aprons, announced as "America's Grandest Love Story." Once again, I was reminded of two facts, first that no movie can hope for a box-office success in America unless the public is absolutely sure that the producer is going to give them "Love," for their money, and. second, that this public evidently is still in a dense fog as far as "Love" is concerned. To advertise Little Women as a "Love Story" is of course too silly to talk about; hardly sillier, however, than the way these two European girls have sky-rocketed to fame, thanks to a public who saw in them the personification of love and glamor. Both Garbo and Dietrich have become internationally famous since their arrival here. Their fame is due to the American public who, with their customary enthusiasm and naivete, immediately hailed them as glamorous women and eminent actresses. If, here and there, some one did doubt whether Garbo and Dietrich were comparable only to Réjane and Duse, about their glamor no one felt any doubt. Did they not portray again and again elegant ladies who had sinned?

For a public, largely made up of women whose idea of a good time is the weekly meeting of the Book Club, and men who do not dare to take a mistress for fear of seeing their "business" crumble about them, glamor is that enviable quality which enhances any good-looking woman who, in expensive surroundings, indulges in illicit love.

Although in everyday American life there exists a great deal of "cute" misbehaviour in public, there is really little grand-scale sinning in private. Screen and stage, then, are the mediums through which a glamor-starved public must be fed.

For several years Garbo was the screen s chief exponent of this exciting quality. One after another, she portrayed American, Russian, German, English and French ladies whose favorite pastime was love, swinging her way through one role after the other, a la Garbo; that is to say, as an intense, affectionate, gauche, romantic child, with a one-track devotion to whatever man her director ordered her to be devoted to. Incapable of flirtations, and with a face and body too individual for fashionable "chic," she was, notwithstanding, put into fashionable clothes and told to portray international neurotics. Usually grave and often grief-stricken, her face would occasionally light up with a radiant smile. When she laughed, it was the laugh of a child: whole-hearted and infectious. Thwarted, she was a child, too: sullen, petulant, ugly. And, in her pensive moments, her eyes held that same puzzling mystery which one encounters in the eyes of babes, the remote look of an alien race.

The American public, however, saw in this child a capricious, passionate woman of the world. Her stubborn silences, her rude gestures of "leave-me-alone," her flashes of gaiety, were taken for the caprices of a temperamental adult. Entirely unlike any American movie actress, on whose cheerfulness the sun never sets, she was alone in her field till Dietrich came along. Built on the same large scale, but more femininely curved, blonde, deep-voiced, given to limitless pauses between words, she was immediately hailed as another mysterious, glamorous creature who, on the screen, lived for love and love alone.

Dietrich came to the fore in The Blue Angel. In that picture, she portrayed a prostitute who, in her free moments, advertised her wares in ribald songs amidst the brouhahas of a Berlin night club.

Strutting about on those fine legs of hers, she was absolutely perfect. Next came an American-made picture: Morocco. In that, loo, she sang, hut in a more subtle fashion, changing her shrill tones to those of yearning, to breathless whispers and amorous laughter. No longer permitted to sing such obvious ditties, it was left to Marlene, and to Marlene alone, to arouse her audience by letting her wide, blank eyes rove, by slowly pulling in that lower lip of hers, by simulating languor, by indulging, in fact, in all the tricks of innuendo. She has succeeded admirably in endowing with the typical mannerisms of the courtesan every character she has thus far portrayed. Blonde, bland, her nacreous shoulders shining like pearls against black velvet, her ravishing face and golden hair mysteriously hidden in the shadows of an extravagantly-plumed hat, she portrays in her screen roles the high-priced courtesan. And in her latest German and French phonograph records (Johnny, Ja, so bin ich, Assez, etc.) there is not the slightest indication that she pretends to represent anyone more romantic than a woman who succeeds in making a profession of love.

Dietrich rose to international fame, thanks to the adulations of the most Puritanical audience in the world: the American. Ignorance is bliss: in this specific case, bliss for Marlene!

Ignorance on the part of her public is not to be wondered at, however. Dietrich is not an American product, but definitely European—European and pre-war. Pre-war and pre-Freud. Ah! Simple time!—when there existed only two kinds of women: the good and the bad. The good kind presents no great complications. The others are more difficult to analyze. Fundamentally alike, they still differ. The European is fully aware of these slight differences, fully aware of the finer nuances which have always existed between ladies who sin, hut who, nevertheless, have had their established place in European society and in the world of Arts and Letters as well.

Described (with a tear which often blotted the accuracy of their statements) by de Musset, Murger, Frondai, and, more realistically, by de Goncourt, Zola, Colette, Charles Louis Phillipe, Schnitzler, Wedekind, Cocteau; drawn by Degas, Lautrec, Rops, Legrand, Pascin, Gros; the prostitute, high and low, has had her share of publicity in Europe. But not so in America, where she figures seldom in Art or Letters. For an American, the differences between a grande amoureuse, a courtesan and a (die, or between the respectable matron who has a lover, and an immoral woman, are hard to understand. Americans, romantic people, have consistently recoiled from a closer inspection of the women who, with the exception of the grande amoureuse and the respectable matron, have made love their profession.

(Continued on page 66)

(Continued from page 28)

It is no wonder then that they mistook Garbo's intense crushes on the screen and Dietrich's facile ones for the manifestations of a passion seen, in Europe, in an intelligent, witty, pleasure-loving woman such as the grande amoureuse usually is. But to the European, the meteoric rise (especially of Dietrich—a less versatile actress than Garbo) is somewhat puzzling. She is of course no novelty to them. Her type is not new to them. They dismiss Dietrich's screen portrayals with a shrug. Lovely? Most certainly, she is lovely; but isn't that about all? So what of it? One's youngest son may attribute to her roles delicate qualities of heart and soul; to the European adult she is too often merely a lovely, cold, egocentric bore. For them she presents not only a well-known type, but, more specifically, a German one at that, not of modern Germany, but of pre-war Germany; the product of kaiserism—that intricate web of social distinctions, in which everyone was classified to a T; where the officer bows and kisses the hand of his betrothed and then saunters forth to meet his "little friend." And where there is always some young girl who, when evening comes, sticks a fresh flower in her blouse, and goes gaily forth, more than willing to become an officer's light-o'-love.

Dietrich, whether she portrays a soubrette, the wife of an American engineer, or a German peasant girl, depicts, for the European public, a type with which they have long been familiar.

Let us consider this type for a moment, as a being apart, a social exhibit, against her continental background. I low are she and her kind usually presented, in countless European dramas and stories?

We see her first, when—hardly more than a child—she is already being instructed in love, preferably by a medical student; a girl who, between school hours, sneaks off to fetch a lover's note addressed to her in care of General Delivery.

Hardly more than a child, yes, but over her still so immature face there flit expressions that reveal her character and predict her future: greed, curiosity, restlessness, discontent. . . . And her eyes fill readily with the easy tears of the sentimental, the shallow.

During her first love affair she is happy, hut eventually the man deserts her, of course. Simply she says: "My heart is broken." The sentimental phrases in which site has indulged so frequently of late do a sudden about-face; she becomes cynical. Soon enough, however, she finds someone who is willing, eager, to console her. Soon enough she is eager to be consoled.

But her restlessness, greed and curiosity grow. She craves a good time, constantly. To eat, drink, and be merry and, above all' not to be alone. She has a horror of being alone—the horror typical of the restless, the unsatisfied woman who is incapable of any profound and satisfying emotion. "Now all is over and once again one is all alone." "Jetzt ist alles aus, und man ist wieder einmal so allein," the song goes. It is a desolate cry at dawn. By night it has become merely ironic.

Always conscious of leading a life of sin, she also consciously caters to what she considers to be man's lower nature. She encounters little else. And she prefers not to. Too much "niceness" in a man bores her. Conversation, discussion, reminiscences, all the trappings of civilization bore her. To please is her profession, to excite— her pride; to have a good time—her aim.

Eventually she takes the sage advice of a colleague or, perhaps, of her mother, and looks out for a more permanent security. For a "friend" with money, position, title. . . . She succeeds. The metamorphosis is astonishing. From a being who is scorned and constantly referred to in realistic adjectives, in fact: from a prostitute, she becomes the fertile subject for romance: a courtesan. She is slandered and ridiculed, yet she knows herself to he envied and admired. Her eyes light up when she realizes that, some day, she may even brighten up History.

She changes. After having her normal appetites satisfied, she craves the artificial. Her primitive desire for a good time gives way to an ambition for a life of luxury, for perfumed baths and warm rooms filled with the slightly stale atmosphere of flowers, fur, alcohol and smoke, while around her lie, pell-mell, gowns, fans, hits of tinfoil, sugared violets and rose petals, programmes, kid gloves, top hats and evening cloaks. It is the disorder of true elegance, the mark of true wealth. She adores it. Ah! To dress at the French and Viennese couturiers, perhaps even to launch a fashion! To be able to hesitate between mink and ermine, ospreys and no ospreys, white and cream-colored pearls. To see pink carnations against frosted window panes or yellow mimosa against the snow. To indulge, in fact, in those little incongruities which are the keynote of "chic", ah, that is life! The only life, for her. She adores it. She adores the admiration of her body, of her face. She adores herself—no one else. She radiates power.

To be seen with her is an advertisement for the man, "her friend". Does she not represent his wealth? True, hut the advertisement is mutual. If he is willing to pay so extravagantly for her favors, these favors must be worth it. No longer do men desire her for her charms alone, but for that for which she stands: luxury.

Love? Affection? Friendship? She does not need them. Adoration takes their place. Nor does she pretend to need them. At least she is honest. She never indulges in that favorite American parlor game: "I love you; do you love me?" She is no cutie, pure of heart, gold-digging while waiting for the love of her life; no repenting Magdalena who mumbles about "fate". She gives no exaggerated meaning to a fleeting moment of tenderness, regret or despair. "From head to feet I am made for love", sings the heroine in The Blue Angel. And this sums up admirably the courtesan's function in life. The American version phrased it differently. "Falling in love again." And that, too, admirably sums up the American's point of view on the matter. For, in this country, rhapsodies on physical charms are only permitted when coupled with romantic sentiments—in most cases entirely misplaced.

(Continued on page 69)

(Continued from page 66)

And so, having considered this typically European type of woman, we may turn back to the work of the two screen stars whom we were discussing earlier in this article.

Recently Garbo has given us her version of Queen Christina, whom she acts exactly as she has acted her dozen or more previous roles, her pure, ingenuous face adequately expressing primitive emotions, boredom, rapture and grief.

And Dietrich? How will Dietrich act Catherine, a queen who, according to Edgar Salt us, was the greatest grande amoureuse of them all? Probably in her customary fashion. But there is no doubt that both will net thousands and thousands for their respective companies. And they will continue to do so until the American public loses some of its easy tolerance for the mediocre and learns to distinguish between alluring mannerisms and legitimate acting, and, above all, between actresses who capitalize only their physical charms and those whom the additional qualities of mentality and intelligence make truly glamorous! But if Garbo and Dietrich have failed in subtle characterizations, they have at least shown a new aspect of "love" to the American public.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now