Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowKing Vidor

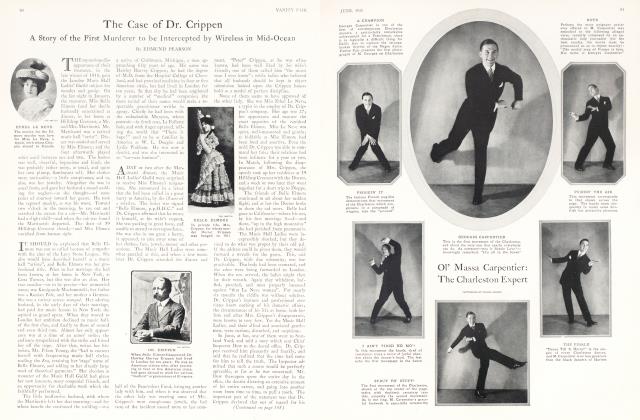

The Fourth in a Series of Twelve Interviews with Motion Picture Personages

JIM TULLY

IT was Michael Arlen who said, "I cannot talk King Vidor's language, therefore why should I try to write an original story for the screen?" This remark will explain why Arlen goes no deeper into life with his books. If the astute Armenian cannot talk the director's language, it is perhaps because Vidor talks a larger language. Compare their work.

King Vidor is a bewildering personality. His features suggest the Oriental. Inscrutable and calm, he blends a pagan outlook on life with Christian Science. He is the eighth wonder of the world—a director who reads books.

He sold a scenario at eighteen years of age and survived it.

Born in Galveston, Texas, in 1894, he has seen life in terms of motion pictures since he was fifteen. Before he was eighteen he had made many contrivances with which to make films. They failed. But he learned about cameras.

He met in his native town a chauffeur who had a motion picture machine. It was during America's trouble with Mexico. Vidor borrowed the chauffeur's camera when he heard that eleven thousand American soldiers were marching into Galveston. He placed himself in an advantageous position and turned the camera on the first group of men. By the time a thousand had passed, the camera clogged. Vidor made a "dark room" out of half a dozen cotton bales. Adjusting the camera, he hurried back to the marching soldiers. After taking a thousand feet of film he sold it to a news reel company for six hundred dollars. With this money he started making motion pictures in Galveston.

HE also wrote screen comedies. At nineteen he took two comedies to New York. They ended in tragedy. He worked as an extra.

He appeared again in Texas, and there fell in love with a girl whom he induced to play the lead in a small picture he began to make. The girl was willing. Her parents objected. So Vidor married the girl. She went a long distance in pictures, and now earns two thousand dollars a week. So much for the wisdom of parents. Her name is Florence Vidor.

When Vidor was twenty and his wife eighteen they decided to leave Texas for California. They bought an old Ford and rattled out of Galveston to a golden destiny. In five years these unknown and youthful Texans were each to earn more than Calvin Coolidgc. But they were to give no more amusement to thoughtful people.

The girl divorced the boy later. Being a romantic young lady, she felt that he would be ruined once she left him. It was indeed a hard blow to young Vidor. He now earns six thousand dollars a week. He also has another beautiful girl.

The Vidors sold the Ford on the journey and arrived in Hollywood nearly destitute.

The young wife worked for fifteen and twenty dollars a week. The husband did the same.

Being a barnstormer of gypsy fortune like himself, I often observed Vidor in those early days. He would walk about from one studio to another with a seedy appearance and a battered brief case. I knew then that he was on the way.

Unemotional and unswerving, he had certain qualities that could not be denied. He absorbs life like a sponge. And like a sponge, he gives nothing back, unless forced.

HE is a shrewd listener. The superficially cultured man in talking to the young director will often make the mistake of feeling superior. But in primitive force, in intuition and a mastery of men and situations, such men as Vidor are the roots of the tree of life, and not its shimmering leaves.

The director once went to Northern California to make scenes in falling snow. None fell. Discouraged, he telephoned to a Christian Science practitioner in Los Angeles to pray that flakes might fall. A just God answered the prayer.

The snow fell, hour after hour and day after day. No man moved from the dingy hotel. And still the snow fell. At last the irreligious assistant director came to his chief.

"Say King," he said, "you better telephone that guy down in Los Angeles and tell him to pray to have this damn snow stop falling. The Big Guy up above's gone crazy. We only wanted a little snow, and He's sendin' down a whole damn avalanche. He thinks we're Perry."

The director telephoned again. The man prayed. His prayer was answered in God's own good time. The snow stopped falling in three weeks.

Vidor was an assistant director and an actor for three years in Hollywood. He sprang into prominence in 1918 with the direction of The Turn of the Road. His next picture, The Jack Knife Man was a masterpiece. It was a picaresque story, and would be considered revolutionary even now. It had no love interest.

Vidor next directed Laurette Taylor in Peg O' My Heart.

He is credited with discovering many screen stars. His discoveries, save in two instances, can be passed over.

He did, however, persuade a girl to leave a restaurant in Mineral Wells, Texas, where she was a waitress.

The girl is now one of the highest salaried film players in the world. She is often billed as "the most beautiful woman in pictures". The ex-waitress went to New York last winter to visit a girl friend who laboured on a newspaper. Her friend had worked late each night to finish a story which she sold for one hundred and fifteen dollars. It was finished the night before the screen star arrived. The ex-waitress wanted a pearl necklace. The two girls went to Tiffany's. The star selected many pearls. When she came to select the smallest one which would finish the necklace she said: "I'll take this one . . . how lovely it is! How much is it?"

And the jeweler answered, "One hundred and fifteen dollars."

The name of the ex-waitress is Corinne Griffith.

Another celebrity whom Vidor discovered was a placid, expressionless little nurse girl named Mildred Davis. She later married a country boy from Nebraska who makes several million dollars a year. His name is Harold Lloyd.

Vidor's greatest fame came from his direction of The Big Parade. This is, in spots, his greatest picture. It is the late war barnumed into an epic. The story itself is twaddle for flag-wavers. But Vidor's filming of the war scenes is masterful.

The man who suggested the story is Laurence Stallings, one of the authors of What Price Glory.

THE war seems to have robbed Stallings of two things—a leg and a sense of humour. His attitude toward it is still sophomoric. One would think that he and Pershing were the only men who went over the top and suffered in their country's cause.

Stallings contributed to this picture what any other doughboy could have contributed. He really wanted a war picture with no war in it. This may shock many log-rollers in the East, but a fact is a fact and comes to the surface like Ivory soap. Vidor, and Vidor alone, is responsible for The Big Parade.

It was King Vidor, who was not near the war, whose absorbent brain put the sweep and the pathos, the humour and the tragedy, into the picture. Vidor knew, like James Cruze in The Covered Wagon and William K. Howard in The Thundering Herd, the dramatic effect of large formations. Cruze had wagons rolling endlessly, Howard had thousands of buffaloes charging, Vidor had trucks, men, and airplanes rushing to the front.

It was also Vidor's direction which lifted Karl Dane as "Slim" to heights of emotional grandeur.

And as credit must be given where credit is due, another thing must be remembered. It was Irving Thalberg, the brilliant young producer who saw the rushes of the film grow out of Vidor's brain each day in the projection room, and who exclaimed: "This is not a program picture! We will make it a feature film."

The motion picture may, or may not be an art ... as you will. It is at least a parr of modern life.

There are some films, such as The Girl l Loved, Wild Oranges, The Jack Knife Man, The Last Laugh, Gypsy Blood, The Stroke of Midnight, and others, which have the harmony of great music. The first named picture, suggested by James Whitcomb Riley's poem, was blended with emotion, poignant and alive. These pictures were not accidental, but were the product of minds and hearts that suffered in the making.

(Continued on page 100)

(Continued from page 46)

King Vidor made of Joseph Hergesheimer's Wild Oranges a perfect picture. He kept the novelist's colour and deviated from the book just enough to heighten its dramatic quality for the herd. Hergesheimer expressed the highest admiration for the director's work, perhaps the only time on record when a novelist was pleased with the direction of his story. Intellect and understanding had met.

This director sees life as the artist of narrative should see it—in terms of the picaresque. At twenty-five he had done more to advance motion pictures than any other man in the world. His Jack Knife Man was Mark Twain writing with a camera.

He has the greatest future of any man in pictures. He talks a world language. He has the ingredients of the artist. He knows how far he can go with his public.

Behind the mask of the Christian Scientist with the Oriental expression a great soul is hidden. It is worth discovering.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now