Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Americans at Muirfield

How, and Why, Mr. Sweetser Won the British Amateur Golf Championship

BERNARD DARWIN

WHEN I first began to write this article there were still sixteen players left in the British Amateur Championship at Muirfield, but, humanly speaking, it appeared almost certain that there would be an all-American finish. I expected to make Mr. Bobby Jones the hcro-in-chief of my article, with Mr. Sweetser honourably mentioned. Then down went Mr. Jones with a reverberating crash before Mr. Jamieson of Glasgow, a hitherto little known young golfer. And Mr. Sweetser was left alone to carry his country's flag. He did it so well and with such dauntless courage, that he clearly usurped the hero's place in the story.

I have now seen Mr. Sweetser win two championships, for I watched his triumph at Brookline in 1922 and 1 have no doubt whatever that he is a very great golfer. Indeed I have had, out of his victory, a little of that somewhat unworthysatisfaction that comes from being able to say, "I told you so." When he came here to England in 1923 he never struck his proper form, or anything like it. His golf was wholly unworthy of him and since nobody quite believes what other people tell them, those who only saw him at Deal, or St. Andrews, would not believe in the game I had seen him play at Brookline. They were far more frightened of Mr. Ouimet than they were of him, and it only dawned on them very gradually that he was going to be terribly dangerous.

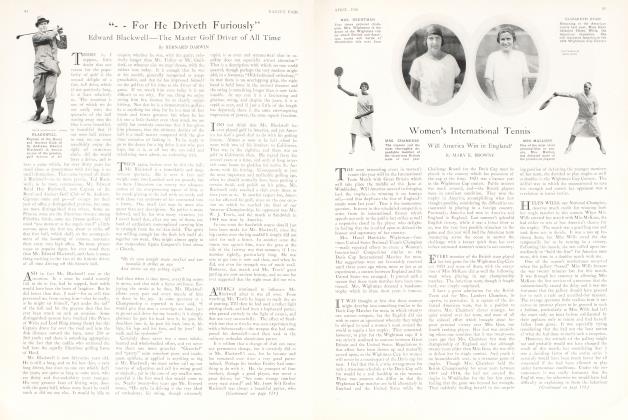

MR. SWEETSER, as I see it, won this ti tie by twovirtues—one moral and one technical. First, he has the fiery, highly-strung nature kept well under control, which makes the match player; of all the American players he seemed to us the most resolute fighter at a pinch, the one most capable of saying, "I will not be beaten." Secondly, he is a truly magnificent player of the iron shot, whether high or low, hit right up to the flag. When once Mr. Sweetser was within range with his iron, his friends' anxieties were at an end and his enemies' hopes failed. The ball was invariably on the green next time and not in the mere suburbs of the green, but right in its very heart.

The Muirfield course, with its rather soft greens, closely guarded, suited this approach shot of Mr. Sweetscr's to perfection—indeed, in parenthesis, it suited all the Americans very well. Though it possesses seaside scenery, in the noble sand hills that tower on its verge, yet in itself it is very like many an inland American course and I know that as soon as the American players saw it they said to themselves, "If we can win anywhere we can do it here." All of them play that high iron shot, which drops the ball spent and lifeless on the green, very well. Mr. Watts Gunn, for instance, plays it with great skill. But no one of them, on this occasion at any rate, was as brilliantly monotonous as Mr. Sweetser.

These two virtues of his were three times jointly illustrated in a conspicuous manner at most critical moments. Three times he had to come to the eighteenth hole, once against Mr. Ouimet, once against Mr. Robert Scott, when in the last eight, and once against Mr. Brownlow in the semi-final. Each time he had to play a firm iron shot for his second (twice his enemy was there before him) and each time the ball came plump down in the middle of the green, giving him a certain four

and a putt for a three. In two of those three matches he was down at some time or other, two down to Mr. Ouimet and three down to Mr. Scott, while against Mr. Brownlow he was the victim of a finish so cruel that it might well have shattered a less undaunted courage. This was indeed the match of the tournament, the more so as everybody knew that Mr. Brownlow was England's last line of defence, and that once Mr. Sweetser reached the final the cup was gone.

After a dour fight, the American seemed to have the match safely won, for he was dormy two, and nine or ten feet from the 17th hole in three, whereas his adversary, in the like, was six or seven yards away. Mr. Brownlow, who, despite his youth, is one of the most entirely placid and serene golfers ever seen on a course, walked up to his ball as if he were playing a friend for half a crown, and popped it straight into the hole. It was too much to expect that applause should not break out at this splendid forlorn hope and when it had died down Mr.

Sweetser missed his putt by the smallest possible fraction of an inch. The very same thing happened at the last hole. Mr. Brownlow played a beautiful second to within half a dozen yards. Mr. Sweetser counter-attacked superbly and got inside him. A deathly silence, a black ring all round the green and down went Mr. Brownlow's putt again and Mr. Sweetser's ball shivered past the edge of the hole. If ever a man felt that he had been robbed of victory by an unkind fate, Mr.

Sweetser must have felt it at that moment, but he never showed it by as much as the twitch of an eyelash. He very, very nearly lost the championship at the nineteenth when Mr. Brownlow, who had to get down in two putts from the edge of the green in two, hardened his heart too much and overran the hole. Then, after a good half at the twentieth, someone had to break and it was Mr. Brownlow who was very short, both with his pitch and his putt, while Mr. Sweetser had an impeccable four.

IT would have been hard on Mr. Sweetser to lose that match. The one match which he was perhaps a trifle lucky to win was that in the third round against Mr. Ouimet. As long as he is fresh, Mr. Ouimet is as good as ever he was, and he had not yet had time to grow tired. He had beaten Mr. Von Elm by 3 and 2 the day before and he started out very well against Mr. Sweetser, being two up at the turn. The tenth hole was of the kind which, metaphorically, sways the fate of Empires. Mr. Ouimet hit a good drive and Mr. Sweetser a poor one: Mr. Sweetscr's second appeared to be engulfed in a bunker but the ball had just enough vigour left to scramble through, though still a long way from the green. Mr. Ouimet put abrasseyshot on the edge of the green, Mr. Sweetser played a good iron shot to within five or six yards but Mr. Ouimet promptly put his long approach putt within five or six feet. All this while it seemed that Mr. Ouimet would win the hole and be three up, but there came a bolt from the blue: Mr. Sweetser holed his long putt and Mr. Ouimet missed his short one. That was an unpleasant shock for the leader and he had another shock at the thirteenth, where Mr. Sweetscr's ball avoided another bunker and he got an undeserved half. From that point Mr. Ouimet began to look a little tired and old, faded and jaded, whereas Mr. Sweetser was as a strong young lion roaring for his prey. They were all square coming to the last hole, but Mr. Ouimet was trapped from the tee and Mr. Sweetser, quite relentless, never gave him the ghost of a chance.

The filial match in the championship needs very little comment, because Mr. Simpson, though a plucky golfer, had been fortunate in getting as far as he did and was not really quite good enough for his place. He drove well and he putted well, but his game was like a man with an excellent head and legs, but no stomach. His game had no middle. Playing as he does habitually on a short course, he did not even possess a brassey till a friend gave him one on the night before.

Continued, on page 104

Continued from page 68

Until he was so suddenly and surprisingly wiped out by young Mr. Jamieson, Mr. Bobby Jones was the magnet to the crowd. Wherever he goes he always will be so, because no game has so beautiful a sight to offer as Mr. Jones hitting a golf ball. His style is a wonder that reveals itself to all. It is as if a small child were to find, lying in the village street, a diamond as big as its head. The child would cry aloud in amazement and so does the least erudite of golfers on seeing Bobby Jones. His perfection of rhythm is a subject for a poet, not for any prose labourer. Mingle in the crowd, and the game has barely begun when you hear some one exclaim, "This fellow has the best swing I ever saw in my life." I suppose that, for him, Mr. Jones did not play, except in one match, particularly well, but he always played well enough to win comfortably and he is just as fascinating to look at, whether he hits or misses. He rose to quite dazzling heights in one match, namely against our then champion, Mr. Harris. I suppose Mr. Harris did not play very well, but really the question hardly seems to arise. In fact he played three holes badly and nine holes quite respectably well, and at the end of these twelve holes he was beaten. Never before has a reigning champion been beaten by 8 and 6.

And then, next morning, down he went by four and three before Mr. Jamieson who, save for Glasgow competitions, was undergoing his baptism of fire. It was a thousand pities that Mr. Jones had put too much trust in the Scottish climate, thrown the blankets off his bed the night before and so awakened with a crick in his neck. This made it painful for him to swing his club at the first few holes. So he began with two wild hooks which meant two holes gone and those two would not come back because Mr. Jamieson entirely declined to let them. I have heard it said, with how much truth I know not, that Mr. Jamieson's one ambition, the thing he had prayed for ever since he decided to enter for this championship, was to meet the great Bobby. If so, then the Day, in capital letters—of which he had dreamed, certainly—found him ready. He played extraordinarily well and extraordinarily coolly.

Of the youngest American players, Mr. Watts Gunn played exceedingly well till he ran into a tornado of threes and fours and had to give in to Mr. Brownlow. I think however, that the greatest impression was made by Mr. Mackenzie, who disappeared in the second round. He surely must be a champion before many years have gone.

Mr. Von Elm, another newcomer and a very fine player, suffered from the same ailment. And, without making too many excuses, some of our best players were horribly attacked by this same bacillus of "nerves". Mr. Tolley who had been playing very well beforehand, was almost farcically erratic in his first round and was easily beaten. Mr. Wethered was far too often in the rough and even Sir Ernest Holderness, whom we have always regarded as a model of trustworthiness and accuracy, had a day on which he topped and sliced as do players of very common clay.

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now