Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowHollywood Parties

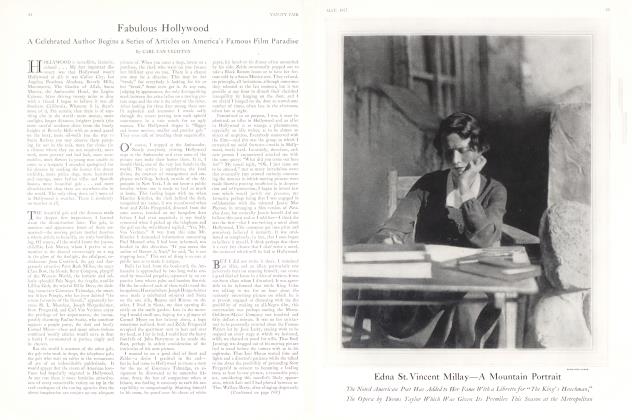

Being a Noted Author's Further Adventures in America's Motion Picture Capital

CARL VAN VECHTEN

THE popular notion of Hollywood parties, I think, has it that they resemble a Stroheim screen orgy. Like most ideas about Hollywood this is entirely fallacious. Hollywood parties—I speak generally; of course, there are exceptions—are both respectable and sedate. For the moving picture actor drink is injudicious: there is the bloom on youthful cheek to consider. Furthermore, there is a noticeable air of studied reserve observable at public functions, born no doubt of a real respect for the ideals that Mr. Will Hays stands for in America's fourth largest industry. Disrespect for these ideals has been known to cost individuals dearly. One still hears stories of illicit love and delirium tremens in Hollywood—there are even cases of spousebreach—but for the most part these amorous tiltings and alcoholic indulgences apparently occur behind locked doors. The local lovers and drunkards do not accept semi-public social engagements. In public the standard of what is called ''good breeding," exemplified by a manner of quiet companionship, is astoundingly high. Compared, indeed, with an average afternoon at an English duchess's the degree of decorum is marked.

I also discovered that another kind of reserve is held advisable in these precincts. Gossip flies as swiftly as an aeroplane over these vast spaces. Discretion, consequently, is the better part of wisdom. Never before have so many pretty gals told me how much prettier other pretty gals were. Never before, or elsewhere, have I heard virtues and talents, domestic and professional, extolled as wholeheartedly as they are at Hollywood. Whenever, in conversation with a star, I inadvertently dropped another star's name, it was a signal for encomiums, not modest or casual, but as a rule, whopping, expansive, exaggerated. I have no doubt even that some of these gals, in the heat of ardent repetition, have begun to believe the compliments they pay to other women.

IF parties are decorous in Hollywood, they are by no means infrequent. 1 went to a great many and enjoyed them all. When we weren't invited to any outside the hotel, we managed to create them ourselves in the bungalows and perhaps the very nicest were the impromptu evenings when we sat in Carmel Myers' drawing-room while Carmel in her soft voice, to the strumming of a ukelele, sang her own tuneful Louella (Gus Arnheim and his band play it every night in the Cocoanut Grove at the Ambassador) or Scott Fitzgerald recited his own plaintive lyric, Dog:

More faithful than a cat,

Larger than a rat,

Dog, dog, dog!

Tom Geraghty brought the trim Louise Brooks in one afternoon; the stately Betty Blythe arrived on another. The number and variety of these beauties amazed me: I kept a check-list at last, striking of! a name as soon as I was introduced to its possessor. May I express regret that I do not find the names of Vilma Banky, Dolores Costello, Dolores del Rio, Greta Garbo, Renée Adorée, and Mae Murray thus struck off. I hope, when they come to New York, they will endeavor to rectify this condition.

About seven in the twilight we sometimes gathered at the window in Siesta to watch the procession descend from the hotel to Pola Negri's bungalow, Reposa, three hundred feet across the lawn, where nearly every evening she dined in state. The solemn march was headed by two white-coated fellows bearing seven-branched, silver candelabra, lighted; others followed with bowls of flowers and tables, while boys with containers which retained the repast at kitchen-heat brought tip the rear. This spectacle was mediaeval and imposing, but one missed music and costumes.

Louella Parsons,—yes, Carmel's song derived its title from her—took me one night to Bebe Daniels' house where Constance Talmadge, Betty Compson, James Kirkwood, Lila Lee, Jack Pickford, Harold Lloyd, and ever so many more were gathered. Bebe and her mother were the most charming hostesses imaginable: the display of refreshment was formidable, the entertainment diversified and informal. After supper some played bridge; others of us watched the unfolding of a new screen play. This is one of the commoner pastimes of Hollywood gatherings (the truth is, in spite of the proverb, that the people of Newcastle prefer coal to anything else), but this particular cinema did not sufficiently serve its purpose—I understand that the wider film public is more easily entertained. At any rate, one after another of the assembled company drifted away from the darkened drawing-room until Betty and I were left alone, when we begged the camera man to desist as the cranking of the machine disturbed our conversation. Later the gals, Miss Talmadge, Louella, Bebe, and Betty, gathered around me and were kind enough to discuss my books for an hour, an hour which may have been something of a strain for them, but which was extremely agreeable so far as I was concerned. It may interest the world—it certainly interested me —to learn that Bebe Daniels is an assiduous collector of books. On this occasion she exhibited, with justifiable pride, several examples of rare Dickens' first editions.

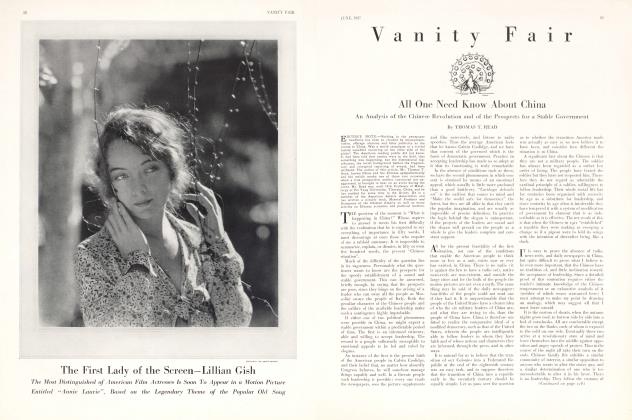

BUT I think I must originally have learned about Hollywood parties from Aileen Pringle who, with Cedric Gibbons, took me to three on my first Sunday afternoon there. We went first to Lois Moran's. It is the ambition of the majority of moving picture stars, I believe, to possess an Italian or a Spanish house in Beverly Hills or Santa Monica, a Rolls-Royce, and a police dog, preferably a white police dog. There must be a sufficient number of police dogs in Hollywood and vicinity to breed a supply which would satisfy the world's demand for these popular canines. The number of Rolls-Royces there must exceed the number of Fords in Richmond, Virginia. However that may be, Lois, who tries to visit New York as frequently as possible, is satisfied, at least temporarily, with a sunny apartment, just across the drive from the Ambassador. About the make of her car, although she generously loaned it to me for days on end, I am not a competent witness. Apparently she is dogless. Her parties are amusing and her mother, about the age, I imagine, of tin* average New York flapper, is adorable. Scott Fitzgerald, also new to the group, was the sensation of this particular afternoon, and Jim Tully, his pleasant Irish face surmounted by a rough thatch of straw-colored hair, belligerent and good-natured simultaneously, more than held his own. Miss Lillian Gish was kind enough to say that she remembered me, and it is quite true that we were introduced circa 1912, in the days when she was playing in Belasco's production of The Good Little Devil, although I had never encountered her since. We didn't get much farther than this when Scott, without conscious effort on his part, took her away from me. However, there was Joan Crawford to consider, the extremely attractive Joan, who the evening before at. a dance given by the Mayfair Club had understood my name to be Van Dyke—whether she confused me with Henry of that ilk I did not ascertain—and who insisted on apologizing. 1 countered with, "You're not like a rush to me; you're more like a perfect still," a spontaneous compliment which served me thereafter on many occasions.

MOREOVER it was often extremely easy to mean it. There were Carmel Myers and her mother. Assuredly there was Patsy Ruth Miller whom after this day I did not again encounter until the very night before I left for the East. Patsy explained that she was busy and that she didn't go out and that nothing would have dragged her out but the prospect of meeting me, and when, on my final evening in Hollywood, I saw her once more— at a party given by Geoffrey Shurlock and Dudley Murphy in that house on Las Palmas with the magic casement which overlooks the lighted city below in much the same manner that Sucre Camr on Montmartre overlooks Paris—when, I say, I saw her once more for the last time, sheJassured me that she had been busy and that nothing would have dragged her out save the desire to say goodbye to me. Naturally, I believed her, but it saddens me to recall that the matter was not urgent enough to drag her out every night. However . . . .

Well, these lovely gals, and others perhaps nearly as lovely—Pauline Starke was expected, but a headache, to my deep regret, detained her in her apartment below—went away one by one, and Aileen whispered that we too must go if we wanted to make the other parties. So we left the Morans—1 quite unwillingly—meeting Florence Vidor coming in as we went out, and motored in Gibby's car to the house of Billy Haines and arrived there just in time to say farewell again to most of the gals we had just bidden goodbye at Lois's. I liked Billy's fresh goodnature and his stuffed olives wrapped in bacon. Presently King Vidor arrived and with him the ethereal Eleanor Boardman, with whom somehow I never found an opportunity to talk, but King introduced me to the favorite and innocent indoor sport of Hollywood, the name of which is curiously derived from that of one of the commoner domestic fowl, the enlivening pastime of fatigued directors on the lot late in the afternoon, and soon Billy was running up and downstairs. A band was playing I'm Lonesome and Sorry.

(Continued on page 86)

(Continued from page 47)

Well, again Aileen whispered that we must be on our way. We were dining, she told me, at Marion Davies's in Beverly Hills. She had explained to Marion that it would be impossible to go to Lois Moran's in Los Angeles, hence to Billy Haines's, in Hollywood, and then drive me all the way back to the Ambassador to dress, and Miss Davies had said, Come as you are, and so we all did. Believe it or not, the band that had played at Billy Haines's was playing in the hallway of Miss Davies's Tudor mansion when wre arrived, late it seems, for the guests had assembled. I recognized Pola Negri at once, chalky white, shimmering in iridescent brocade and pearls, and after I had been introduced to my hostess, who wore a gown as blue as her eyes, I went to Miss Negri's side to thank her for having appeared in what was supposed to be a film version of my book, The Tattooed Countess, but which finally bore so little resemblance to that novel that people who have seen it—it was called A Woman of the World—have asked me from what book of mine it was derived. Miss Negri was prettily contrite about this and adjusted to simple courtesy, but Miss Negri as a personality is imbued with a somewhat severe grandeur which it is difficult to penetrate, even in her lighter moments. Patsy was here too, and Seena Owen, and Mrs. Glyn whom I had met in Paris in 1908, but who miraculously seemed years younger, and Max Reinhardt, whom I have met twenty times, but with whom I have never conversed because he says he doesn't speak English and I assuredly do not speak German, and Morris Gest with whom I have never conversed because when I am with him he does all the talking, and Vollmoller, and the exquisite Billie Dove, and so many more that at table, being a trifle near-sighted, I could not clearly make out all the faces.

At dinner I sat next to Aileen, whom I always find an agreeable companion. There is an ironic tinge to her most serious comment and a touch of sentiment in her most jocular remark, qualities which give her a very real fascination for me, aside from what she has to say and how she has to look. At dinner she devoted an amazing amount of time to me, considering the eminent gentleman who was seated on her right.

I have never watched Miss Davies on the screen—I have attended comparatively few moving picture exhibitions—but I may state that "in person" she possesses a quite extraordinary talent, aside from her ability to dance and 'sing. Aileen had told me of Miss Davies's imitations and after dinner I begged for a view. To my astonishment, this required preparation, a prolonged preparation which I only understood when she entered in a costume, a wig, and a facial transformation which uncannily represented the absent Lillian Gish. Miss Davies was sufferingly wistful for several moments, indicating successfully in deft caricature the mannerisms of her sister star until, as she departed through an open doorway, she disappeared with a leap and a whoop. I discussed this and other interesting matters with Patsy until Miss Davies appeared in the guise of Mae Murray. After that, at my urgent request, Miss Davies turned her very devastating attention to Miss Negri, indicating with no unsure hand the somewhat false theatricality to which Miss Negri is addicted in some of her more exotic impersonations. Miss Negri smiled, but I am not sure that her smile implied pleasure. Then Mrs. Glyn admitted that she too desired to be imitated. "Charlie imitates me pouring tea," she announced, "and I am sure that Marion can too." It developed that Marion could. Her head crowned with Mrs. Glyn's symbolic braid, cloaked in ermine, lorgnon in hand, Miss Davies described IT after the inimitable fashion of the creator of Three Weeks. This imitation, too, was devastating, but doubtless it is better to be imitated and devastated than never to be imitated at all. Mrs. Glyn certainly chuckled and chirped her delight. The masterpiece of the evening followed. Depriving Morris of his outer garments, claiming his broad felt hat, painting a huge wet mouth all over her lovely face, Marion gave us her impression of how Monsieur Gest behaves at rehearsals. These imitations were undertaken in no spirit of malice. Miss Davies was consistently good-humored, even boisterous, but all fine caricature is critical as well as complimentary.

It was all, as I seldom say, over too soon and departures were in order. I had thought to be delivered at the Ambassador by Miss Negri, as she too made her home in one of the bungalows, but she made pretty, but definite, objections. She had promised to drive Reinhardt and Vollmoller and Gest back to the Garden of Allah— thus they have christened the hotel which was once Nazimova's Hollywood abode misspelling, many believe, her first name—and there would be no room for me. Meanwhile I had lost Aileen and her car, as she was working early in the morning and long since I had urged her to go home. Not desiring to walk, I plead, almost wept. I suggested that I was willing to sit in somebody's lap. Miss Negri, in her simple dignity, was quite certain that I could sit in nobody's lap. Such a thing was quite unheard of. The car was full and that was all there was about it except that I might come to tea with her on Tuesday at five. On Tuesday, however, I was pleasantly detained way past that hour by Lois and Gladys Moran at the Paramount Studios, so that when I finally arrived—the distance between the studio and the Ambassador is about equivalent to the distance between London and Paris—it was too late to see Miss Negri. Nor, unfortunately, did I encounter her again during this visit to Hollywood.

(Continued on page 90)

(Continued from page 86)

Mrs. Glyn, who also makes her home at the Ambassador, rescued me from the danger and embarrassment of walking to the hotel from Beverly Hills. It was with the white, cold, mysterious-eyed Mrs. Glyn that I drove away from Miss Davies's party to the accompaniment of much improving advice, uttered in that lulling monotone which is the unique delivery of this lady.

"Do not," she adjured me, "be a slave to cigarettes. Be master in everything. Look at me, cold, impassive— that is why I wear ermine ..."

"But seething within?" I suggested.

"Certainly," she replied coldly, "that is not your affair. I let nothing touch me," she continued with a little more warmth. "I protect myself from outside influence. That is why I can give myself to my art, that is why my books will make two hundred million readers happier and better fifty years hence, that is why all the people who play in my pictures acquire a sincerity they have never had before or may never have again.

"Look at Aileen, a clever, beautiful girl, but in Three Weeks I gave Aileen a soul. Look at Conrad Nagel! In Three Weeks I gave that poor boy passion. Do stop smoking cigarettes. Achieve a cold exterior and develop your soul."

I promised to consider this sound advice. The next day on the Famous Players-Lasky lot I encountered Mrs. Glyn on the set where Betty Bronson was making a picture of the English writer's called Ritzy. Mrs. Glyn was most cordial, inviting me to seat myself in one of those forbidding chairs prominently marked with the owner's name. Presently the director approached and she introduced him to me: "Mr. Rosson, let me present Mr. Van Vechten. Mr. Van Vechten," she went on to explain, "is one of the great authors of the world," and turning to me she prettily queried, "What have you written, Mr. Van Vechten?"

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now