Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Catholic Issue in Politics

A Consideration of the Recent Smith-Marshall Correspondence Regarding Church and State

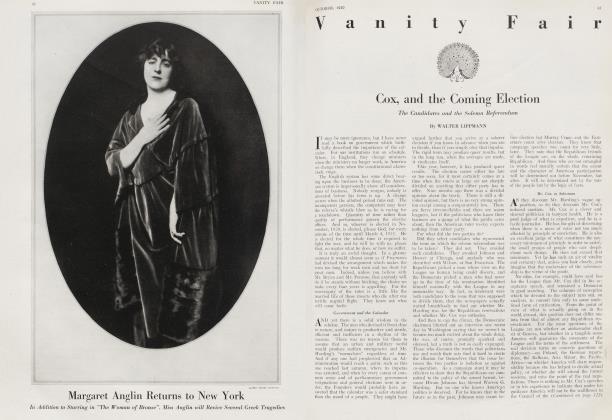

WALTER LIPPMANN

FOR more than a century most Americans have believed both that a religion was no test of a man's fitness for public office and that only a Protestant should be elected President of the United States. This paradox has often been noticed, but until about the year 1923 it was a merely theoretical difficulty without practical importance. For until after the second election of Governor Smith there had never been a serious contender for the Presidency who was not a Protestant.

Since the rise of Smith desperate efforts have been made by Democratic politicians to find some way of avoiding a direct test of the question whether a Catholic is eligible to be President. They have pointed out that Smith is a wret, that he belongs to Tammany Hall, that he is a cockney. But these objections however sincere and weighty have been regarded by the mass of people as unreal. Protestants and Catholics alike have felt in their bones that any Democrat who can be elected Governor of New York four times would under ordinary circumstances have an irresistible attraction for the politicians. They may cross their hearts and say that they have no objection to Governor Smith's Catholicism, and they may even think they mean it, and yet they will not be believed. Governor Smith is so clearly available by every conventional test, except that of his religion, that the conviction has now become set, and is now, I think, irremovable that his Catholicism alone stands in the way of his nomination.

SINCE the Catholic voters are a predominant part of the Democratic Party outside of the South, the question of Smith's nomination has become one of life and death to the party. He cannot be rejected without alienating an absolutely essential part of the votes on which the only possible chance of a Democratic victory depends. There are now some twenty million Catholics in the United States. They are no longer, as they were a generation ago, largely confined to a class who do the menial work and do not have to be taken into account in the government of the country. They are a substantial and powerful part of the electorate, and few of them are in a mood to acquiesce under a concrete test in the unwritten law that they are second class citizens who cannot aspire, no matter what their other qualifications, to the highest office in the land.

These are the circumstances, roughly, which have made Mr. Marshall's open letter in the Atlantic Monthly, and Governor Smith's reply, an event of such historic importance. Mr. Marshall on his side formulated in the shape of a documented argument the inarticulate fear which inspires the old American tradition against allowing a Catholic to become President. In effect he summarized what remains in the modern world of the mediaeval claim of the Roman church to temporal power. The Governor on his side made a declaration of belief as an American Catholic which amounts to a complete disavowal of the mediaeval theory of the Catholic's power. In this disavowal he claimed to speak for American Catholics, and prelates qualified to speak for the American hierarchy have publicly approved his utterances. The net result of the correspondence, therefore, has been to make articulate, definite, and formal separation, in questions of polity, between the mass of American Catholics, and the historic claims of the Roman Church. There are precedents in the history of American Catholicism for the position which the Governor has taken. But never has the distinction between Catholicism in Twentieth Century America and the Catholicism of the Middle Ages been stated with such unqualified clearness.

THE momentous character of Governor Smith's declaration can only be understood by realizing exactly what was the question Mr. Marshall put to him and exactly what was his answer. Mr. Marshall's argument can be compressed into very simple form. The Roman Catholic Church teaches in the words of Pope Leo XIII that "the Almighty has appointed the charge of the human race between two powers, the ecclesiastical and the civil, the one being set over divine, the other over human things". But who, asks Mr. Marshall, shall decide what are the divine and wdiat are the human things? He then cites Pope Pius IX who wrote that "to say in the case of conflicting laws enacted by the Two Powers (i.e. , civil and ecclesiastical), the civil law prevails, is error." Against this he cites the decision of the Supreme Court (Watson vs. Jones) that religious liberty in America is qualified because religious "practices inconsistent with the peace and safety of the State shall not lie justified." And from this he argues that since the Roman Church claims the right to decide what things are within its jurisdiction, whereas the American theory makes the civil power the judge of its own jurisdiction, no faithful Catholic can give unreserved allegiance to the civil power in America.

THE argument comes down then to this crucial point: suppose the Church claimed that a question affecting education or marriage or foreign affairs was to be determined by the principles of the Roman Church, and suppose the executive, legislature, and courts of the United States claimed that the question was to lx* determined by them, which authority, the ecclesiastical or the civil, would Governor Smith or any other good Catholic recognize as final?

Governor Smith's reply, which avowedly was made after consultation with priests of his Church is as follows:

". . . . In the wildest dreams of your imagination you cannot conjure up a possible conflict between religious principles and political duty in the United States, except on the unthinkable hypothesis that some law were to be passed which violated the common morality of all God-fearing men. If you conjure up such a conflict how would a Protestant resolve it? Obviously by the dictates of his conscience. That is exactly what a Catholic would do. There is no ecclesiastical tribunal which would have the slightest claim upon the obedience of Catholic communicants in the resolution of such a conflict." Governor Smith's answer, then, to the fundamental question as to which jurisdiction he would recognize as final is that he would follow the dictates of Ids own conscience in each particular case. This is a very far-reaching declaration. It amounts to saying that there is an authority higher than the utterances of the Church or the law of the land, namely "the common morality of all God-fearing men," and that the conscience of Alfred E. Smith, and of every other individual is the final interpreter of whether that common morality has been violated.

If Governor Smith were not a Catholic in good standing, if the reply had not been made with the approval of members in good standing of the Catholic hierarchy, one would be tempted to say that he has avowed the essential protestant doctrine of the right of private judgment in all matters where any secular interest was involved. But said by him, under these extraordinary circumstances, buttressed with citations from American Catholic prelates, there is only one possible conclusion which can he reached: it is that for American Catholics there is absolutely no distinction between their attitude and the attitude of Protestants. The ultimate authority, says Governor Smith, is conscience. He makes no qualifications. He does not say conscience as authoritatively guided by the Pope; on the contrary, he says, quite explicitly, that the guidance of the Pope is to he judged, wherever a secular interest is affected, by the determinations of conscience. Citing Archbishop Ireland on "the Church's attitude toward the State", he affirms that "both Americanism and Catholicism how to the sway of personal conscience".

(Continued on page 78)

(Continued from page 31)

If any form of words could put an end to so ancient and deep-seated a controversy as that between Protestantism and Catholicism, this avowal would do it. The deep Protestant fear that Catholics submit their consciences to an alien power with its seat in Rome is here answered by the radical assertion that for American Catholics their consciences are a higher authority than their Catholicism. I call it a radical assertion for there is little doubt that Governor Smith in adopting Archbishop Ireland's statement has aligned himself unqualifiedly with that wing of his Church which is furthest removed from the mediaeval ideal of a truly Catholic and wholly authoritative synthesis of all human interests. Governor Smith is the latest, and by no means the least, of a long line of Catholics who have almost forgotten, indeed may never even have heard of, what the Church conceived itself to he in the days of its greatest worldly splendour and ambition. Certainly one detects in him no lingering trace of the idea, speculatively at least so magnificent even to those who, like this writer, were not reared in the Catholic tradition—the idea of Catholicism not as a religious sect hut as a civilization. The Catholicism of Governor Smith is the typical modern post-reformation nationalistic religious loyally in which the Church occupies a distinct and closely compartmented section of an otherwise secular life.

The position of American Catholics like Governor Smith is very close to being what J. N. Figgis calls "the final stage in that transposition of the spheres of Church and State which is, roughly speaking, the net result of the Reformation". For "in the Middle Ages the Church was not a State, it was the State; the State or rather the civil authority (for a separate society was not recognized) was merely the police department of the Church. . . . All these functions have passed elsewhere, and the theory of omnipotence, which the Popes held on the plea that any action might come under their cognizance so far as it concerned morality, has now been assumed by the State on the analogous theory that any action, religious or otherwise, so far as it becomes a matter of money, or contract, must he a matter for the courts".

I said that the position occupied by Governor Smith came very close to being that of this "final stage" in modern development where the omnipotence of the State is substituted for the mediaeval omnipotence of the Church. It is not quite clear just what is Mr. Marshall's position although it seems to me to imply that "Americanism ' means the absolute supremacy of the civil power in all matters which the civil power chooses to consider as within its jurisdiction. If this is what Mr. Marshall really thinks, it is not what Governor Smith thinks. For the Governor puts his personal conscience above the secular claims both of Church and State, and denies the absolute jurisdiction of both.

This, I venture to believe, is not only a sounder Americanism in the historic meaning of that term, hut a more truly enlightened and civilized doctrine than that which is now so widely preached to justify the idolatry of the political slate. For while it is all very well to argue that the Church of Rome shall not have the last word in deciding what things men shall render unto Caesar, and what to God, it would he a sinister philosophy indeed which went on to say that Caesar must have the last word as to what things belong to Caesar, and what to God. 1'his is just as real a dilemma, in many ways it is a more practical dilemma than any with which Mr. Marshall confronts Catholics. Does Mr. Marshall claim that the political state must he as absolute today as the Church claimed to he in the Middle Ages? His silence implies that he is not disposed to examine the credentials of Caesar. Yet I doubt whether after consideration Mr. Marshall would finally say that Americanism requires that a man shall surrender to Caesar, acting through popular and legislative majorities, through proletarian dictatorships or plutocracies, dominion over all the interests of life.

Governor Smith is closer to the founders of the Republic than Mr. Marshall who seems to assume, at least by implication, that Americanism must mean the superiority of Americanism to any religious teaching, and to any conception of morals. Governor Smith is not only more truly American in the historic sense of the word, hut he is more enlightened in his premises. For in denying the temporal power of the Pope, he does not fall into the very easy error of attributing universal power to the State. He leaves the question of civil obedience where it must always remain in a complicated world for any man who is neither a fanatic nor a theorist; to adjustment in specific cases by the conscience of the individual acting upon the evidence before it. And by leaving it there he puts upon the civil power and the ecclesiastical alike the burden, which ought always to be theirs, of justifying themselves continually in practice to whatever wisdom there may he. in the consciences of men.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now