Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

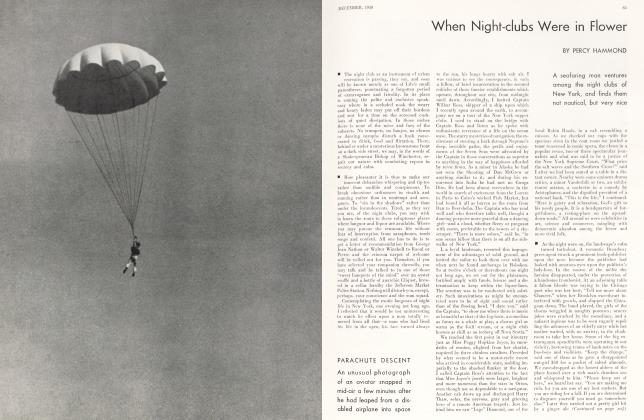

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowCame the Din

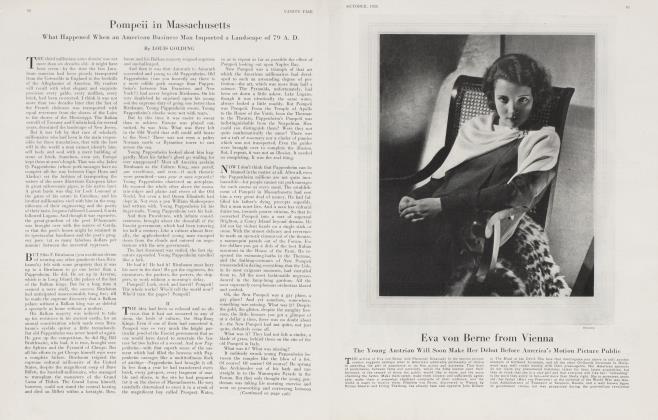

A Lover of the Silences Laments the Talking Motion Picture in a Last Stand Against Bedlam

PERCY HAMMOND

MR. SHAW once announced that the cinema's most aesthetic charm was in its silence. That was in the distant epoch of the nickelodeons when, if weary of the bray of actors' voices, we could rest amongst its shadows and escape the dissonances of dramatic elocution. Mutely the characters tip-toed across the screen, more muffled than in a pantomime. From their gravid lips the syllables fell noiselessly, illustrating the author's thoughts in wordless dumb-show. It was possible, then, to afford the over-worked ear an occasional holiday wherein it might repose, clam-like, in the midst of the Drama's warring emotions. All that ardent Drama-lovers had to do in order to escape occasionally from the prattle of their Hearts' Desire was to retreat to a cinema and find refreshment in its taciturnities.

Silence, like a poultice,

Came to heal the blows of sound.

As Life grew more vociferous, however, the "Gems" and "Bijous" stirred uneasily in their native hush. All around them existence was clamorous. The mum symphony of the spheres was drowned out by the insolent clatter of air-ships defying the holy stillness of the skies. Architecture, which once "reared its fabrics as quiet as a dream," began to make whoopee in the loud staccato of its riveters and the thunder of its blasting and piledriving. Even Music, the heavenly maid, abandoned her celestial whisperings and got herself a megaphone. The inaudible horse gave way, as a means of transportation, to the motor-car with its deafening screeches and horn-toots. The radio joined aviation in making a bedlam of the firmament, introducing "static" among the cosmic crashes and explosions. War's engines roared more stentoriously than ever, and the cannon's boom of Gettysburg and Agincourt was but popgun to the Argonne. The Globe, in both its aesthetic and material habits, developed a hullabaloo in the chorus of which only Lit'rature and the cinema did not join.

IT was not to be expected that the screen would continue indefinitely to take no advantage of the acoustics. Like most infant mongrels it was precocious, and it chafed because it could not be heard as well as seen. Surrounded by an uproar in which it was unable to participate it was discontented. Upon its baby fingers it therefore framed an appeal to its nurses. "Learn me to talk!" it petitioned in the quaint, Hollywood patois. Tended as it was by those who could refuse it nothing, the dubious boon was granted. Wizards and scientists were hired at stupendous wages to desert more valuable experiments that they might instruct the cinema how to untie its tongue. In numerous laboratories the Magi laboured for years over their alembics while Hollywood waited nervously to be endowed with speech. There were times when Art's giant cub grew impatient with its attendants. Now and then, like a papoose Caliban, it ruffled the Californian serenities with gauche outbreaks of misbehaviour. But it had a fundamental faith in the promises of its maestros, and felt sure that eventually they would unleash its shackled larynx and permit it to blow at will upon the most favourite of human instruments, the windpipe.

Came, then, the din. After the usual period of abeyance the cinema finally discovered that it had a voice. This it proceeded to lift in opposition to the racket of "El" trains and American statesmen. The erstwhile calm of its shrines was abolished by clamours of utterance. No longer did its nebulous silhouettes flit spectre-like athwart our vision accompanied only by the soothing sibilations of the projecting apparatus and the distant ballyhoo of the barker upon the sidewalk. No longer could fatigued wayfarers depend upon its soft seclusions as a place to slumber. The Vitaphone, like Macbeth, murdered sleep, to say nothing of Romance. Lovers who once could nestle heart to heart and neck to neck in the movies' peaceful recesses were driven to register their vows in precincts less hubbub. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Paramount, Fox Films, Universal nor any of the Warner Brothers will ever appreciate how important their improvements have been to insomnia and birth-control.

I AM one of those old-fashioned fellows who go from place to place in a ship, a street car or an automobile. Change dismays me, and I would not trade my steamboat or my Rolls-Royce for all the Bellancas, Sikorskys and Fokkers in Mr. Levine's garage. It was years before I succumbed to the safety razors. When and if I drink liquor I prefer the passe, pre-prohibition stimulants to the new-fangled beverages. I still regard Eugene O'Neill's oldtime dramas more highly than the advanced product of Em Jo Basshe or John Dos Passos. To me the fresh red rouge of yesterday's female faces is more decorative than the exotic pallors of today's. Quiet, old-homey women, such as Miss Texas Guinan, fill me with more comfort than do the startling Mrs. Clem Shaver, Mrs. Hanna-McCormick, or either of the two Mabels, Boll and Willebrandt. I yearn for hansom cabs, lager beer and the other ancient conveniences available when grandpa was a boy. So when I deplore the ambitions of the movies it is just the lazy lament of one who resents the onward march of civilization.

Mr. Shaw, after encouraging the cinema to keep its mouth shut, was of course among the first to unseal its lips. A bewhiskered Pandora, he oped the box and permitted the mischiefs to escape. At heart a benign old devil, he knows as well as you that Mighty plays, like mighty griefs, are dumb, and that his sanction of the movietones is not conscientious. Insincerity is the badge of all the Drama's tribe; and Mr. Shaw grins diabolically in his trivial chit-chat to the camera. It is probable that he is one of those gifted with vision and that he is willing to sacrifice his present tastes to the promotion of the art cinematic. It may be that the night will come when gallons of resonance, added to a jigger of developing fluid will make the films another cocktail of Culture.

I boast that years ago I attended the accouchement of the Movietone. Summering on the Lake Cayuga littoral, hard by the Auburn Penitentiary, I was neighbour to Mr. Theodore Case, Jr., a dilettante scientist whose hereditary riches enabled him to potter with the elements and to coax them under his control. One day he decided that he had mastered Nature, insofar as it was related to the moving-pictures. He thereupon summoned Samuel Hopkins Adams, Will Irwin and me to his observatory there to have our speech and gestures photographed simultaneously. Mr. Adams spoke of President Harding, the hero of Revelry; Mr. Irwin of Secretary Hoover, and I of my pet twins, Thespis and Momus. When, later, we saw and heard the resules of the experiment we agreed to let it go no further. We were like carillons with modern tongues, "out of tune and harsh". The canary serenades of our silver throats were changed into the caterwaulings of a betrayed pibroch. Mr. Case returned to his cabinet to perfect his machinery. But—I was one of the dogs he tried it on. Consequently I have the right of a pioneer to find fault with it.

However it is the Vitaphone version of The Lion and the Mouse with which I am most familiar. In that historic charade Miss May McAvoy appears as Shirley Rossmore, a heroine. Beset by the trials essential to leading ladyship Miss McAvoy flits to and fro during several acts, graceful, pretty and unaffected. She seems for a time to be a fine player, competent to renew one's waning interest in the knack of histrionism. Unhappily the Vitaphone causes her to open her trap, as the saying goes, before the piece is over. At once all fascination vanishes. It is as if she had inserted a bugle in each of her nostrils and is blaring nasal tattoos and reveilles. "Idonwanchermunny," she exclaims in bellowing accents to the villain, disdaining his proffer of a bribe. When it is time for her to speak my favourite dramatic speech:

"Won't you—be seated?" the words come out as if they were being performed by Creatore and his brass band.

THERE is ample room for another art and the talking pictures will soon occupy it. We are, as usual, in the throes of revolution and some of our greatest film grandees are candidates for the guillotine. In case the chimes of Imperia Starling, Greta Garbo, Betty Nice, Clara Bow or Doug and Mary are not friendly to the Kodak, into the tumbril they will go with their yelps and meowings. The prospect is both consoling and tragic. We shall miss the snores of tired drama-lovers, but in their stead we shall have the outcries of more and more actors. At any rate everything will be okeh with Roxy, and Major Bowes.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now