Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Musical Mentality

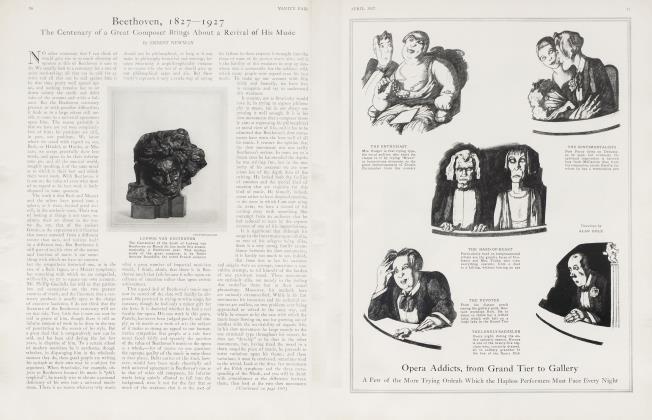

A Noted Critic Investigates the Intellect of a Few Famed Musicians From Their Revealing Memoirs

ERNEST NEWMAN

CERTAIN French writer of the eighteenth century, in the days before Germany counted very much in European letters, asked in all seriousness and in all the pride of race whether a German could have esprit. I have often been asked by incredulous cynics whether musicians have any brains, and I have been mortified not to be able to settle the unflattering doubt with a confident affirmative. Perhaps the question ought to be put rather differently. That musicians have brains, and sometimes quite good brains, seems a fair deduction from some of their non-professional achievements, though even there the ultimate quality of the brains may be a subject for dispute. Beethoven, for example, showed a capacity for business that would have carried him far in Wall Street when he promised the Mass in D, as Thayer says, "to four or more publishers practically at the same time", and then gave it to none of them; but what sort of brains did the colossus show in the historic affair with Himmel? This pianist, to get a bit of his own back after Beethoven had worsted him in a pianoplaying contest, wrote to tell the great man of a wonderful Berlin invention about which the whole town was talking—a lantern for the blind. Our good Beethoven carried the news of this latest marvel of science all over Vienna, and was furious when it was broken to him that Himmel had fooled him. Wagner, again, showed brains of a sort when he told a number of fibs in his autobiography and arranged for the publication of this to be delayed until thirty years after his death, by which time, it was tolerably certain, all the people about whom he had fibbed would be dead and so unable to contradict him; but had he had just a little more brains he would have taken care to destroy all his own letters and those of other people that prove him to have been fibbing.

THE question, then, perhaps ought to be not tout court whether musicians have brains, but whether it needs much brains to be a musician; that is to say, whether the brains that some of them undoubtedly possess and the faculty by which they do their musical work do not exist in more or less watertight compartments. I am moved to this speculation by a prolonged course of reading, lately, of the memoirs of musicians, and more especially of singers. The question whether singers have brains is one that has been anxiously debated for centuries; the verdict of the court has not yet been pronounced, but the evidence seems to tell against some of the accused. Lest the numerous dear friends I have among singers should feel, after this, like cutting me the next time we meet, I hasten to explain that in the first place I don't mean them, and in the second place that the problem is not whether Madame This or Signor That has brains qua the delightful and intelligent Madame This or Signor That whom we meet in the ordinary affairs of life, but whether he or she has any brains worth speaking of qua prima donna or top-note tenor, and whether brains, in the usual technical sense, are required in large quantities to achieve world-wide distinction along these lines. For really, when we read the biographies and autobiographies of some of these charming people we may be pardoned for having our doubts. That some of them have been geniuses in their own sphere is beyond question. Equally beyond question is it that some of them reveal themselves, in print, as the possessors of intelligencies of a marvellous and touching simplicity.

THE absence of anything approaching what might be called a commanding intellect is shown not in any failure to be sensible in the ordinary affairs of the world (indeed, they are often shrewd enough in these) but in the failure of most of them to exhibit as much intensive thought upon the problems of their special art as the average plumber does upon the problems of plumbing, or the average athlete upon the problems of physiology. I have been through volume after volume of singers' biographies and memoirs without lighting upon a single really intelligent reflection on music or musicians. If these people have any reasoned ideas on the art they practice, and that some of them practice well, they are singularly successful in concealing them from their readers. Many of them are not merely bundles of childish vanity—as is shown by their complacent citation of euologies of them written by newspaper morons hardly a degree more literate than themselves—but vulgarians to the marrow of their bones, as is shown by their servility towards titles, their eager recording of any flattering fatuity that some noodle of a royalty or aristocrat may have uttered concerning them. How does it come about, one asks oneself in sheer bewilderment, that an artist who can so admirably express a Active nobility of soul in her singing is so plainly, at the centre of her own soul, a mere pin-point of obsequious vulgarity? We who liye in London,—a city in which titles, being six a penny, are not taken seriously— are alternately amused and revolted at the large amount of space given in the memoirs of musicians, of some of whom more dignity might reasonably have been expected, to recording the notice that some titled nonentity was gracious enough to take of them, and the meagre amount of space .given to the expression of anything that could be called thought upon the art in which they have been eminent. Nor is this true of singers alone. I particularly have in mind the memoirs of a man of decided ability in more than one field of music, who knew intimately some of the most distinguished composers of his time, and who, instead of telling us something about these people that would throw a direct light upon them, prefers, out of the essential smallness of his soul, to give us pictures of himself purring contentedly on the hearthrug of some insignificant duchess or other.

I suppose the root of it all is their vanity, that colossal vanity that has been fostered in them by years of adulation. The strongest head, indeed, the sincerest artistic nature, is not immune to this subtle poison. Two of the best autobiographies of recent years are those of Isadora Duncan and Chaliapin. One rises from the perusal of each of these books with an added respect for the writer as a person of complete artistic sincerity, a being possessed by something bigger and stronger than his conscious self. Yet even these two are not exempt from the pathetic vanity that makes them cite with gusto the newspaper and other records of their successes. When the ordinary prima donna tells us how an enraptured crowd unharnessed the horses and drew her carriage in triumph through the streets to her hotel, we smile indulgently if a little sadly, knowing how sweet these memories of former popularity must be to one whose day, she knows, is over; but there is a touch of wryness in the smile when we find an Isadora Duncan vulgarising the grand natural lines of her selfportrait by petty vanities of this sort.

Things move in a mysterious way in this complex world of ours, and I sometimes wonder whether the deathblow to this particular form of prima donna vanity may not ultimately be given by—the motor car. I am away from my books at the moment, but I seem to remember a passage (in Tristram Shandy?) in which Sterne satirically attributes the decay of oratory to the substitution of coat and trousers for the ancient toga. The Roman orator could always work on the emotions of his readers by producing, at the critical moment, an orphaned child from the folds of his robe,—an effect impossible with the male dress of today. Perhaps the substitution of motor for horse traction will deprive the prima donna of one of the most intense of her traditional joys; an adoring crowd may take out the horses from a brougham, but I cannot see the most conventionally romantic melomaniac, however anxious he may be to do the correct thing, taking the cylinders out of the lady's car.

STILL, other means of ministering to the singer's vanity will remain,—the grateful letter, for instance, the love declaration, and the gift of jewellery. It is not every prima donna who is naive enough to tell us, as one of them did recently, that the gentleman who showered his wife's jewellery upon her after one of her concerts was shortly afterwards certified as a lunatic; as a rule we are left, in cases of this sort, to infer the lunacy. But there will always be the type of person who writes to the famous singer in terms like these (I quote from a lately published biography): "I have roughed it for twenty-eight years in the Australian bush, but your song Abide With Me has taken me back to my mother's knee". And whoever and whatever else may fail the prima donna, there will always be the royal person to thrill her with his exalted approval. No singer, it is true, has yet soared to the giddy heights reached by Max Beerbohm's Zuleika Dobson; it will he remembered that the Sultan of Turkey "conferred on her the Order of Chastity and offered her the central couch in his seraglio". But Zuleika had a close rival in the prima donna who, as she tells us with an audible throb in her lovely voice, actually met with the approval of no less distinguished a royal connoisseur than his Majesty "King Kalakua. King of the Sandwich Islands": "he did not forget me, for later when he was in England he came to hear me again at Covent Garden, on this occasion decorating me with the Order of Merit, and giving me an invitation to sing in the Sandwich Islands". The voice of King Kalakua may not often be heard in those councils that decide the fate of the world; but after all, say what you will, a royalty is a royalty, and the Order of Merit of the Sandwich Islands is a distinction that does not come everybody's way.

Continued on page 138

Continued from page 72

Perhaps I did these performers an injustice when I complained of the general lack in their pages of intelligent reflections upon their own art. Some of them, it must be admitted, atone for this by a rare profundity of utterance on other subjects. The singer to whom I have just referred has informed an admiring world that "India is a most interesting and fascinating country. The climate and the whole conditions of living are so totally different to other countries." The grammar may not be impeccable, but the information is invaluable; I can remember nothing comparable to it since the day when Queen Victoria, on her first visit to Germany, noted in her diary the astonishing fact that, though German is such a difficult language for foreigners to learn, even tiny German children could speak it quite fluently. And did not Isadora Duncan, at the tomb of an Egyptian prince who died six thousand years ago. make the astounding discovery that "if he had lived he would have been six thousand years old"? One of Flaubert's delights was the compilation of a dossier de la betise humaine—a book in which he jotted down anything he came across in the Press of the day that showed forth the true glory of human intelligence, such as the remark that "the moment a Frenchman crosses the frontier he is on foreign soil". Flaubert died too soon: he should have lived on to the days when singers and dancers wrote their memoirs.

Dreadful stories are told in every opera house of the self-esteem, the egoism and the jealousies of the singers. Let no one believe these scandalous libels; we have only to turn to the memoirs of these worthy people to discover that, on her own frank admission, each truly great prima

donna is as modest about her own accomplishments as she is enthusiastic over those of the other ladies. It is not often that we come upon the sad spectacle of a singer who does not think much more of her colleagues than of herself. It is with evident pain, for instance, that Minnie Ilauk records certain other singers' narrow-minded jealousy of her,—a jealousy surely pardonable, however, when we reflect how galling it must have been to these others to realise their hopeless inferiority to so well-night perfect a singer as Minnie Ilauk confesses herself to have been. Will it be believed that on one occasion, when Minnie was taking a call, Madame Artdt "deliberately pinched" her and "forced me behind her in order to take my place"? Do these things really happen sometimes in those abodes of love called opera houses? And how grievous it is to find Minnie Ilauk telling us that Lotte Lehmann's "jealousy knew no bounds; she was known to be the most cantankerous member of the whole Court Theatre crowd", and Lotte Lehmann, in her memoirs, saying that "Minnie Hauk was a great favorite for a long time with the Press and the public, but she was already less popular, and least of all with the members of the company. She was equally unamiahle towards all her colleagues, whether men or women."

Alas, alas, can these things be? Can goddesses sometimes, though of course rarely, have so poor an opinion of each other? But the life, though hard, has its compensations. Lotte may not have adored Minnie as much as was the latter's due; but Minnie can console herself with the reflection that "cravats and coiffures, race-horses and yachts, were named after me, and the dresses I wore at receptions were imitated by many ladies." And Minnie has even surer titles to immortality. Among her other achievements, she has corrected the delusion, so long held by musical historians, that the composer of Il matrimonio segreto was one Cimarosa; we have it on Minnie's authority that the composer of that masterpiece was Rossini, and she ought to know, for did she not sing in a trio from it at the Albert Hall? Bayreuth is another subject on which she is entitled to be listened to with respect. For she was there when the Rheingold was produced in 1876: the occasion was truly a memorable one in the history of music, for "I remember that I wore a light blue crepe de Chine tunique over a blue silk skirt, with roses in my hair, and diamond ornaments".

I sincerely hope that nothing I have said in this article will discourage the output of singers' memoirs. We cannot have too many of them.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now