Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowCitizens of Moscow

Russians of All Types and One Class, Seen Under the Auspices of Tolstoy, Resignation and Gaiety

THEODORE DREISER

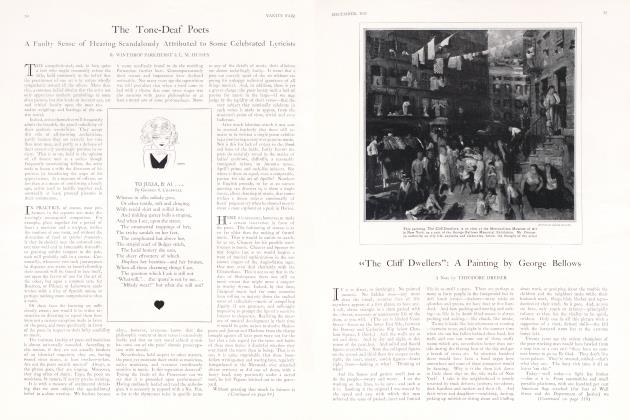

MOSCOW is a different city from any you are likely to see in Europe, Asia or anywhere else—different in colour, tone, mood. Those rambling, disjointed streets and squares! Those numerous and agreeable surprises in the way of open spaces, trees, monuments, vistas. Such drab, moth-eaten and yet colourful palaces and once grand private homes, obviously the former residences of capitalists, traders, social parasites, social blood-suckers! Oh! And the churches—384— count 'em! But with such lovely green or gold or brown or red or white or purple pineappley domes. And a bell tower packed with a most amazing variety of bells—eight, ten or twelve, to a church,—bells that emit such a clatter of sweet, tinny, sombre, and even ominous, sounds as never anywhere else issued out of any belfry, I am sure. And then cars and busses and droschkys and trucks and queer little tatterdemalion wagons hauling almost nothing. And fat drivers. And thousands of men and women in padded furs and skirts, looking more like walking mattresses than anything else I can think of. And fur hats or caps—shakos or woolen drums or muffs, (only always on the head)—that should add glory and distinction to even a Shriner band or royal guard.

I WAS sometimes so astounded by a quite uncalculated effect approaching along a thoroughfare that I was speechless. "Do my eyes deceive me?" "Does this man actually feel that he is all right?" "Can anyone truthfully say to me that he does not feel a . . . ah, — well, slightly in the public eye?" They can and would. Except for yourself. newr to this amazing world, he or she attracts no attention. In short, I do now aver that I could put a tin saucepan on my head, a pair of Dutch wooden shoes on my feet, wrap a Navajo blanket or a bed quilt or mattress of any size, weight or colour around my body, strap it all on with a leather belt, and sally forth and attract not so much attention as I would should I appear in a silk hat and evening clothes. It is Russia. It is U. S. S. R. It is that amazing medley of one hundred and sixty-three nations or tribes that have now joined in one common bond and are on the march to a better day. Everything goes. Everything comes. And so unconscious. You stare. You smile. You may even feel as you do when a grand parade is approaching along a lifeless Kansas or Nebraska street. But you will never say that it is not a good show. Never!

And in this connection, a few words as to a few restaurants. There are not many places in Moscow—or all Russia for that matter—outside the rooms of a person, here and there who chances to have the wit and temperament for food, ease and pleasure—where one can lounge and dine and jest and trade wisdom or nonsense, as you will, with a few people who are not bent on saving the world. Yet I found three. And each one different; the food not bad; the spectacle diverting. One of these (knowing no Russian I recall no names) wras a Tolstoyan affair—vegetarian— and near the new Moscow post office. And patronized in part at least, I fancy, by those who still see in the quondam Sage of Yasnaya Polyana a true prophet of perhaps the only way of life. According to his teachings, if I recall aright, one was to eschew luxury, or even comfort, eat sparsely of vegetables, think deeply and charitably, and love each and every other from church-bug to Tsar. Well, so be it! There may be everything to it. Who am I? But this restaurant:

In Russia today, you know, there is not enough furniture to go round—there never has been, I fancy—and what is present is usually not only poor in quality but sometimes rude, or crude, and worse yet, decayed from a much better state. So that assuming a restaurant at .all, it may as well be, and usually is, knocked together from whatsoever scraps of furniture as at the time could be gotten together for the purpose—long, short, square, oblong, and round tables of different woods, colours and dimensions, and usually without linen. And chairs of equally variegated forms and textures. And similarly a rather startling diversity of cheap cutlery and dishes—tin, or paper, or glass, or porcelain. And paper napkins so small and thin that at first I thought they were small and colorless doilies.

But now is the dinner hour, let us say. And, having found a place and saluted such friends as you see, you (almost cafeteria fashion) make a list of the things you desire from a dimly mimeographed menu and carry it to a cashier or order desk, where you leave it pending service by one of the several women in waiting. But meanwhile here is the company. And now is the time to study the effect of a philosophy not only upon the diet but the dress, the manners, and the physical features of a male or female disciple. The tall brows; the elongated and waxy Russian faces; the limp and faded and flossy character of some of the beards, the reflective and too often sunken, and not infrequently blazing or burning, eyes; the long, thin, and so often graceful, hands; the limited and too often worn or faded, and almost always, as it seemed to me, inadequate amount of clothing for so icy a world. Positively, on my one and only visit, I sat enrapt. For, true to the tempo of the Russian mind, here you found a group that was seeking to live its intellectual faith —to eat as it thought.

AND into the room now comes one Russian —not unlike St. Francis of Assisi—and wearing what to me was a compilation of shreds and patches, a true Joseph's coat of many colours, but folded gracefully, if inadequately, around a long, thin body. And taking from his head with an easy, graceful gesture, a brown cap so old that it suggested a thousand moths. But the wearer looking about and smiling, now here, now there, and finally seating himself with two others of his ilk and indulging at once in animated and obviously cultivated conversation. The gestures and glances alone were ample testimony. And at last, after a period, having set before him in one small dish five or six thin, limp scallions, boiled; a boiled potato; and %itli it a cup of probably sweetened whey. And this, with a piece of brown bread, making his meal. And the same lasting for long over an hour, nearly two.

And at another table, five young Russians of from twenty to thirty years of age. And obviously here because of that tendency in all humans to go where they can find agreeable companionship—in this instance definitely idealistic. For like so many others in this place, they were physically thin and pine, though at the same time radiant of a certain phase of mental energy—whether sound or not I could not know. But corruscating and gesticulating. But in such poor and, as it seemed to me, inadequate clothes. The thin, plain blue or black trousers! The somewhat ancient and not very attractive ties an.d shoes! And usually a coat and trousers of different and quite frequently inharmonious colours. And an overcoat none too warm.

But the eyes! And the energy! "Can you make out what they are talking about?" I asked my guide. 'They are students, I think, from one of the universities. They are talking just now of some lecture on biology." "And would say they were Tolstoyans, following his social theories?" "I doubt it. This is a good and rather cheap place to eat. They probably believe in vegetarianism, for the time being, anyhow. And they can meet all sorts of intellectuals here. Here comes one now."

AND as he said this I turned to the arched entry way that gave in from another room. And if St. John of the Wilderness had appeared, I could not have asked for more. Long, oily, light hair, protruding below a round, fezshaped fur hat. And from the chin and cheeks of a long, egg-shaped face, pale, lymphatic yellow whiskers. And above these, pale watery blue eyes. A long, soiled, and patched, yellowish-brown cloak was buttoned close to his neck and drawn in at the waist by a piece of string, its material looking to be of linen or cotton and decidedly not warm. His feet and legs were encased in boots of felt ascending to the knees. Yet with an air of great serenity he nodded first to this one and then to that, as taking off the patched cloak and the fur cap he seated himself at one of the nondescript tables.

"And who is this, pray?"

"Sarusoff, one of Tolstoy's own disciples. He knew Tolstoy here in Moscow. That makes him a man of authority, one of the leaders in the new, or by now you would have to say the old, cult. You know these Tolstoyans still dream of turning his teachings into a kind of religion. Simple living, unostentatious dying; love one another here on earth; hold all things in common. You know, a kind of religious communism."

"But have they any form of organization or ritual?"

"THAT is just where the trouble lies. They have not. If they had only some material procedure to hang it on, some form of doings in a temple or a field, the thing might go yet. As it is, communism has rather taken the wind out of his teachings. It is trying to do the same thing on a purely economic basis, without religion or the Christ-like precept. But still they meet here and there to read and study him. And next fall they are to celebrate the hundredth anniversary of his birth. Then you should come and see. I wouldn't be surprised if hundreds, even thousands, of such dreamers as these turned up here in Moscow. They are a mystical people, these Russians. A fantastic idealist like Tolstoy appeals to them. Dostoievsky in all of his books indicates as much."

I studied the old man, now making his meal of spinach, onions, and some black bread and beer. And thinking what? Still how to save the world in a new way? He was in his element here, surrounded by a large company which if not exactly like him was in his key—mental if not mystical—capable of making him feel at home just as his presence there made them feel at home—a phase of the actual Russia of today.

The second restaurant was a quaint, pleasing, and yet none too brisk, little place over by the Lubjanski Prospect—wherever that is —and kept, as I was told, by a highly refined Russian, who, in better days, had been the somewhat worthless heir to a considerable estate (taken away from him by the revolution, of course)—and his since acquired wife. For he had been an unmarried, social butterfly then, knowing no trade or profession, and once the revolution broke, without sufficient means or convictions, maybe, to escape. The charm of this place was that he, because of his early training, knew what constituted good food—a rather rare thing in current Russia. Also, and not strange to relate, he had a taste for music—the violin, no less, which he would play when the mood was on him, and almost invariably accompanied by a young pianist who came to play with him for his meals.

A COMMONPLACE but clean little suite of rooms—occupied after the guests were gone by host and wife as their living quarters —comprised the restaurant. A small, sheet iron stove held the center of the main room. And upon window sills, tables and ancient piano, paper flowers—almost the only winter flowers of Russia. They grow few real ones —a luxury, you see. Yet here and there a stubborn and determined rubber plant. And on a chair near the stove a large, fat, yellow, green-eyed Russian cat. And near the cashier's desk—this side the piano and between it and the kitchen door—a table with some magazines and papers, at which mine host, when he was not taking orders or making change, could sit and read.

But what was most pleasing, or perhaps I would better say engaging, of all, was mine host himself, long, lank, blond, debonair, a little casual, and I am sure a little, let us not say lazy, but easy-going. For what is life? And what can one do in Russia these days? Had not his early patrimony been swept away? And did he really believe in communism, anyhow? Most likely he did not. It might not last. Besides, what could the heir of an extinct bourgeois family expect of such a government? So, oh, well, here were papers and books. And his wife could cook. (She appeared to be chained to the kitchen, his devoted slave, apparently.) As for himself he dangled here and there over the tables, an easy social and intriguing figure—full of grace and good will and a personal selfsufficiency which enveloped him like a cloak. And his manner in taking your order was that of one who was meeting you, not so much for the first time but after a long absence.

But most of all I liked, I think, the way he exchanged sociabilities with those he knew. There was the table and the papers and a book or two. And between whiles—between piano solos by the young student and his own solo or duet contributions, he talked to one and then another coming in or going out. Now what was this rumour of war between Lithuania and Poland? Surely, nothing serious. Yet, maybe. Yes? He hoped not. Russia certainly needed peace for a while now, and if Poland began ... (I am quoting the translations of my guide.) And yes (since a young girl had come in and. was pausing near him as he sat back at the table), he was reading this book—White Love—it was not so bad. A story of the Kolchak frontier. But not much better than a movie. No, he wouldn't advise her to read it. And to my companion on leating he said he was glad to see him again. It had been weeks since he had been around, or so it seemed. "A charming fellow," added my guide as we went out. "He has just that something that isn't real exactly, but he makes you feel that way. And that's why I like to come here and bring other people, too."

BUT the most outstanding thing, and indeed the one thing which to my way of thinking conditioned and distinguished the whole situation was something which had nothing to do with the food or the man's manner, but was rather a touch of the spirit and the economic condition of the Russia of the hour, and really made the man's own attitude toward his present physical and social state. More, what I now refer to neither my companion nor any one else in Russia would have commented on at the time—given it not so much as a passing thought, since it was nothing more than a reflection of Russia's courageous determination to make the best of what is in order to create the better or ideal state of tomorrow. But the truth is that in December mine host had on a second-hand spring suit of a very light texture and showing much wear, so much so that it had acquired two small patches, one at the knee and one at the left elbow. And these of cloth which did not match. And, more interesting still, when it was his turn to play—(and he was by no means an indifferent violinist)—he would rise and going close to his friend at the piano would take down his violin and lifting it with his left hand hold it to his chin in such a way that the elbow patch, which was of light blue cloth —the nearest to the grey he could find, perhaps—would come into view. And then, crooking his left knee slightly as he swayed here and there, lost in some dream of Grieg, or Brahms, or Chopin, he would bring into view the second patch, directly over the left knee and of greenish-brown cloth,—a most outstanding bit; but perhaps the best that could be achieved at the time. And then, the applause bursting, for there were always many in his restaurant, he would bow, his patches somehow holding the eyes—or at least mine. And then a customer entering, or one passing out, he would begin again in his easy, social way to talk.

BUT those patches. And that spirit—the spirit of present day Russia, really—a most courageous and wise viewpoint,—by the aid of which he, and all present day Russia for that matter, wave aside and give the death blow to all slavish and brainless materialism,—its fashions and conventions which so dominate our western world. The flare with which they demonstrate the non-necessity of our fashions and lavish material needs—the grace and assurance with which they dismiss them. I swear it was like a. dash of cold water in the face of a man who sleeps hoggishly and brainlessly. It was like a flag that is run up on a tall battlement, a signal and a call to a great and good fight, perhaps the death of something not worth while. It made for me the best and the most fascinating meal and scene that I had eaten or contemplated in all Russia.

Continued on page 102

Continued from page 56

And then the Gypsy Restaurant. I know it has another name but I do not know what it is, or where it is. But since it is a night restaurant of sorts —the only place where a little public night gaiety is to he found in all Moscow—it will not he hard for anyone who knows Moscow to identify it.

I was taken there by Reswick, the representative of the Associated Press, and we timed ourselves to arrive at midnight, previously taking the trouble to telephone for a table. And knowing the economic and social restrictions of the Soviet Empire at the time, I was more cheered than not, for I had expected little. It is so in Russia. You know that all bourgeois gaiety is suspect, and certainly a night restaurant of any description is bourgeois—and so likely to be patronized by conniving capitalists, concessionaires, money hoarders or grafters who are not in sympathy with the communistic ideal, and so not entitled to gaiety, or indeed relaxation in any form. Yet such is the nature of the human temperament, as well as the Russian, that it is difficult to taboo quite everything. The heart of man is really unregenerate. And being so, one must compromise a little. Also, a resort of this kind is in the nature of a trap. It tends to draw the unregenerate and the sometimes gilded flies out into the light, where they can be pounced upon by the virtuous and self-sacrificing. Ha! You will hoard money, will you? You will graft or profiteer and then come to such a place as this to make merry! Very good, come to the Cheka! Come to the office of the G.P.U. We will look into your affairs. Perhaps you have not paid all your dues, accounted all of your takings.

So, as I say, I was not a little pleased to find a quite cheery room, not badly lighted; the food, as it proved, good; the music consisting of ten genuine gypsies of assorted ages and sizes all sitting on a platform, tambours or balalaikas in hand, and indulging at intervals in various spirited and yet invariably mournful airs, which recited, as I was told, how love, and spring, come early and are soon over —how follow the brief, scorching days of passion and then the sad, brown leaves of autumn and the snows of winter. "Gather ye rosebuds while ye may." And yet, so different is the Russian temperament from ours that it can dine and dance to these airs. And again, so different is the Russian temperament from ours that it finds nothing incongruous in a night restaurant where the music is furnished by ten none-too-attractive and. in certain instances withered and wrinkled gypsies, their ears dangling bangles, their brown, clawy hands thrumming tambours or strings, their throats chanting wistful and yet defiant tunes of the sorrows that befall us all. Indeed, my guide, who was surely a Russian man of the world, was enthusiastic in their praise, beating time with his hands and stamping with his feet and saying how lovely the old sad airs were—how wistful and tearful and hence wonderful. And all the other diners equally loud in their approval.

"Yet imagine this in New York or Chicago," I thought! "Imagine any night club employing such a worldworn and sinister group as this! Imagine! 'Tis Russia, and none other than Russia."

But I am running ahead of myself. What really interested me at first, and after, were the patrons themselves. Here we were, in the only public night resort of any consequence, and yet see how it was—low-ceiled and decorated not at all, the furniture of that same mixed and au contraire character that marked the Restaurant Tolstoy. And apart from a few men and women in evening dress (how very few, indeed!), an assortment of garments that left me breathless. Upon my word, this is the new, free, different world, this Russia of today. For here now comes a strapping young fellow, his plump, pasty-faced girl on his arm, and while she is in flouncy white and wears high-heeled slippers, he is in the standardized dark blue blouse and leather belt, his trousers passing into high polished boots, his oily black hair combed backward in long graceful lines over his ears. And behind him, at another table, with his girl, as dark and curly as an Italian Juliet, a blondish youth in a light summer suit far from new and such as one might wear in July—never in December—yet as swagger as you please on account of it. For mark you, these western suits of whatever vintage, even with an occasional patch, are not to be lfad in Russia at all. They do not make such cloth—(too luxurious as yet.)—and they cannot afford to import it. The cheaper grades cost plenty here, God knows! And so should a foreigner arrive and sell such a suit or leave it indifferently behind —Presto! a Russian—below the rank of an official, say—in a new and smart outfit! And the wonder of it, English or American! Cut right, and with a distinctive pattern. Ha, ha! And yet, as you say to yourself, the knees bag, and surely the thing doesn't fit as well as it should. But who are you to judge? Are not you the outsider? It is the Russian, the insider, who will be impressed by this. And so ... no wonder he is applauding loudly, and tlu« girl, too.

But our evening is young. Wait! Here comes a Kalmuk, with an overcoat that I swear has somehow the look of a corset attached to a hoopskirt—(the skeleton frame, I mean) and with a fur hat that has the sions of a very, very, very wide and decidedly truncated dish pan. And with him his girl or wife—small, brown, black-eyed, intense, and even a little savage-looking, and in a combination of things half silk, half linen, that are green, yellow', brown, black, purple. You gaze and are impressed. For after all, if this were a stage— the chorus of some colourful show— it could not be so much better.

And then next, a really portly Russian. of perhaps the trader or bloodsucker type—fat, red-cheeked, doublechinned, puffy-necked, a really beastlike type. And with him two attractive and yet semi-obese girls or women of not over twenty-six or seven, with a heavy, meaty sensuality radiating from every pore. The white flabby double chins and crinkled necks. The small and yet fat and even puffy hands. The little, shrewd, greedy eyes, half concealed by fat lids. And yet they too are moved by. those gypsy laments, and sing or beat time with their heavily bejewelled fingers. Surely some Cheka agent or G.P.U. will see these and call our fat friend to an accounting on the morrow. Surely, surely.

Continued on page 104

Continued jrom page 102

But along with these the artist types. And writers. Ho, should they be excluded? And why, pray? The outer door is heard to close and here enters, as brisk and flippant as the chill wind he brings with him, Ivan Ivanovitch, say—painter or sculptor or poet, and looking all three. That flaring chrysanthemum hair. The thin, yellow-, downy mustaches. The long, waxy, artistic, and yet vital hands. The swagger and even defiant or tolerant air. You think perhaps that he is to be overawed by poverty, or defeated by the gaiety of this place. Go to! Heigh, ho! We artists will show you what art and poverty is like, and genius also! And so, an overcoat! (I am not exaggerating. God forgive me, should I! And so an overcoat (and in this Moscow weather) of nothing other than cretonne or its loom sister —a vari-coloured and flaring, posterish thing of quite Chinese exuberances, as who should say the more of this, the better. And to top the thing off— with yellow gloves. And worn with what an air! Surely in this case it is the manner and not the clothes that make the man. But with his girl on his arm or preceding him, in a trim English walking suit, which has been come by God knows how! Yet not expensive. A thing that could be picked up in London for twenty shillings, or in New York on Fourteenth Street for nine or ten dollars. But here in Moscow, heigh, ho!

Indeed I might continue this for pages. For Moscow, and all Russia for that matter, is today picturesque if poor—all the more so because it is poor. And patches and rags and makeshift and mixtures of the most amazing character are the veriest commonplaces of the hour. Yet as for being deplored—go to! Who is rich? Who can be rich? And as for bourgeois, capitalist, fashions, pouf! Also tush! We will do these things as we wish, devise new ways and means. And so you yourself, fresh from London, or New York, and with all your capitalistic and other class notions still strong upon you, are suddenly sw-ept into the newness, the strangeness, the freshness of it all. Heigh, ho! Bully for a new day! Bully for a new idea! To hell with fashion plates, with what the west, or the north, or the south, may think! This is Russia. This is the new, shifting, shimmering, changeful, colourful, classless day of a new social order. And where formerly the lord, and the millionaire, and the snob, and the social ass, with his theories and conventions ruled or set the pace, we now have this. And heigh, ho, for it! Heigh, ho, for a cretonne overcoat! Heigh, ho, for a fur hat four feet wide! Heigh, ho, for flaring skirts and top boots and blouses and patched pants and homely gypsy singers who chant sad chants of dead loves and youth to make a midnight restaurant gay! For this is a new world, a fresh deal. And let us hope that no real harm comes to it, lest something fresh and strange and new and of glorious promise pass from the eyes and the minds and the hopes of men.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now