Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowIn Praise of the Immoderate

Why We Are Compelled to Tolerate Bad Taste in Order to Have Good Taste in the Arts

LOUIS GOLDING

I HAD for a long time thought myself, in a vague sort of way, a Hellenist. But when I met Jimmy Bowles at a house-party in Gloucestershire, I speedily learned the temerity of thinking about anything in a vague sort of way. For Bowles is not merely a leaderwriter upon no less Olympian a journal than the Times; he is a Fellow of All Soul's. Or I ought perhaps to phrase it that he is not merely a Fellow of so Olympian an institution as All Soul's, he is a leader-writer on the Times. You can't be a Hellenist just like that, vaguely, in the void. It is as precise an intellectual condition as being a member of the thirtysecond order is a condition of masonic merit or being on the committee of White's is a condition of social grace.

The particular heresy which provoked against me the thunders of Bowles's canonical wrath was my assertion that the mean could not be golden, that I would be served with no half-measure in my art. Jimmy's eyebrows beetled. His lips paled. But I would brook no warning. I persevered with my praise of the immoderate. The excellent and the intolerable, I cried aloud, these are the only things we can tolerate in Art. And then it was that Bowles rose in his wrath. And so he solemnly, with book, bell and candle, pronounced exorcism upon me, and I was hurled out of the bright perfect communion of Hellenism into a grey barbaric limbo, among Goths and Persians and Scotsmen and Escjuimos. Out of this same void I still lift my forlorn voice and wave my ineffectual hands.

LET us have immoderation. On the inl corruptible world of Marcus Stone let no withered leaf fall! Let no neo-Cubist temper me his angularities with the sinister seductions of a curve! Let no tinkle of melody corrupt the abrupt cacophonies of Satie! There is, in preposterous art, a dizzy rapture which it shares with supreme art. Mediocre art is rice pudding. Hence Swinburne wrote with such enthusiasm of the execrable poetry Frederick William delivered in kingly labour; hence the gentleman in the footnote to English Bards and Scotch Reviewers responsible for the exquisite lines:—

O to pen a stanza For the Marquis of Braganza!

0 for a lay Loud as the surge

That lashes Lapland's sounding shore.

is a more eminent poet than the author of Parisina and the Baedekeresque Pilgrimage. Mayfair has her graces of scimitars in stone, of tall wicked ladies poised delicately like the blue willow-herb; Chicago flaunts her bad banners in the eye of the moon. But who would elect for his purple revelries, the Bronx?

The excellent and the intolerable, I repeat, are the only things I can tolerate in Art.

I recall with delirious delight a picture exhibited by the "Allied Artists" in London some years ago, in which a Boy Scout was presented, embalmed among lurid and portentous sun-flowers—the worst picture I have ever seen. When I return to Oxford, I have no time for the intermediate virtues of Exeter College, whilst I walk a tight-rope of ecstasy between Magdalen Tower and Mr. Ruskin's Balliol Chapel. What use have I for the courtly mediocrities of Vandyck when I can rise to Heaven through the cleft clouds of El Greco or swoop to Hell with a California movie-poster? And there is a lady from Cincinnati, who recently sent me her poems; and there are the poems of Pindar. What need assails me then for the strophes of Sir William Watson?

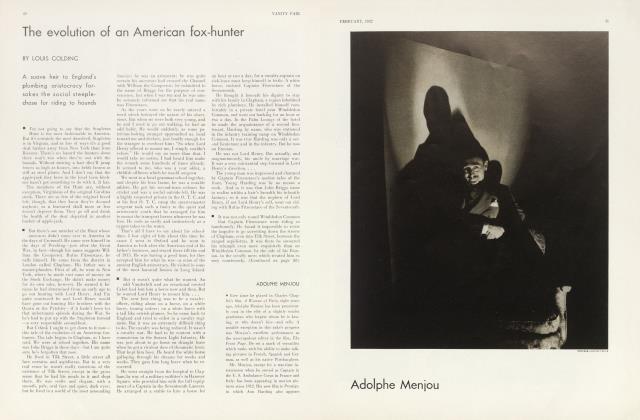

I ASK you. Bethink yourself a moment. How can there be any disputing of a thesis which establishes the Arctic and Antarctic Poles of Art as equal foci for starry adventure? I think it will be most readily conceded than in the art of acting the law works with most strength and speed. We may accept as the best acting that defiant flaming penetration of the actor into the veins and marrow of his author's conception, at the same time as he most splendidly expresses his own uniqueness. A mediocre player fits into his part as into a readymade suit; for some anxious moments or minutes he achieves the interchange between John Bloggs and Sophocles, or, rather, between John Bloggs and Oedipus; but how soon a Bloggs reduced even from his own unexciting stature and texture protrudes through Oedipus as the straw stuffing through the joints of a doll! But supremely bad acting is a triumphant and relentless delineation of the innermost secrets housed by the thoroughly bad actor. He struts the stage, his red heart visibly pumping, the shanks of his skeleton dangle and clank.

Here, I think, the reason lies that makes New York theatrically the most exciting city in the world. Nowhere else do actors and plays so excellent and so infamous rub shoulders with each other so intimately. Paris achieves a certain Sorellesque technique, London a certain Etonian propriety, but they only rarely achieve the peaks or abysses of New York. It is not only in a metropolis that you may hope to attain either extremity. In Mantua last year I saw an Italian fit-up company act so transcendently that I grow pale with bliss and pain at the memory of it. This same year in Marrakech, which lies in Morocco under the tall Atlas mountains, I saw a company of such cretins perform a revue entitled Un Chleuh dans la Soupe, that I grow pale with bliss and pain at the memory of it. But the experience whither all this is leading was more beatific than Mantua or Marrakech, more astounding than Broadway. For upon one and the same evening, in one and the same theatre, the miracle of synthesis was accomplished. The extremes coincided. The fallacy of the Hellenist's golden mean was for me forever exploded.

This was the way in which it happened. My friend and I had several hours to spend in a certain provincial city before a midnight train bore us townward. From the very moment we set eyes upon the Tivoli Theatre, we knew that no other place in that city could so reward us for our patronage. Here there was not chance that the fitful evasions of the mediocre would insult us. The very title of the revue, pictured upon shrieking posters—Topsy Trotter Turns Turtle— was a paean of imbecility. And that no detail should escape us, we entered the Grand Box, so commanding with several senses a panorama of stage and draughty wings.

The chorus was expatiating on the appetites of married men for a weeny bit of tootsywootsy in the "pile" moonlight. Such mournful and such haggard ladies, such corncake voices. "But this," we whispered to each other idiomatically, "is the stuff!" Upon the appearance of male flesh in the box the chant was temporarily suspended until the ladies had made valuations and comments. The silk-hatted leading gentleman, who had been reprimanding the totally inefficient limelight man, gesticulated ferociously chorus-wards from the shadows. The singing was resumed, with sudden ascents into aerial static, with sudden descents into mediumistic ventriloquisms. The dresses bawled with every unintended discordance of colour, magenta rubbing shoulders with terra cotta, shrill green with kaffir pink. After ending upon a variety of top-notes the chorus filed regretfully away, uncovering thus a perspective of marble halls like a stevedore's paradise. The comic man entered, his nose painted hilariously scarlet, a dreadfully funny little bowler hat perched on the back of his head. . . But his eyes, his eyes—woe's me for the sorrow of his eyes. He made animadversions upon his mother-in-law, and would have no truck with bloaters.

HE broke occasionally into an unintended falsetto, weary as the petulant calling of the plover, until we hid our faces. The silk-hatted leading gentleman, pathetic backwash from d'Orsai, Brummell, d'Aurevilly, had an altercation with the comic gentleman, who attempted a somersault to make an effective exit, but found it just beyond his powers and ambled off miserably. Hereupon, the swell, the masher, Fitzhenry was his name, told us what a boy he was all the way from Piccadilly to the Roo de la Pay, and how duchesses swooned when he came near them. His coat sagged like purses at the shoulders, there was a hole above the heel of his left shoe. But as day deepened into the long late glories of sunset (fumbling with orange slides) and sunset waned and the moon came queenly into the hushed silences (excruciating blue light concentrating on tombstone teeth), we learned that there was no disentwining his heart from the roses on Topsy's breast (appearance of leading lady, suitably rose-cinctured, and languishing duet making the soul sick). When the great earth-quaking sunrise came clanging up behind Cathay—the introduction of a pagoda and two pig-tale-coiffured girls had transported us thither—the mature charms of the leading lady were revealed. No make-up could abate the antiquity of her eyes nor the involuntary twitchings of her lips. And when she danced an incompetent little dance with Fitzhenry, we looked sadly away as from an intimacy of the toilet.

Continued on page 108

Continued from page 88

So this pageant of execrable art was unrolled upon this superb and dolorous evening. And I remember how casually I turned from the stage, crowded with its gibbering mannikins and looked over tbe stalls and the smoky pit, to the further corner of the theatre; and how suddenly my eyes were arrested and my soul stood still; bow the discord ebbed from my ears; how my eyes were bathed with cool light; how the walls around me crumbled in a wind from faery; how I was brought before Beauty face to face.

I cannot explain whether it was illusion or vision; but as I knew Beauty when I first gazed upon the vast inverted lily of Etna from the citadel of Castrogiovanni, and Beauty in a tense earthless moment in a fugue of Bach, and Beauty upon the lips of a Bellini Madonna in the Brera at Milan —so in that vulgar and ridiculous theatre, so magically transformed, or, more truly, so pierced and penetrated,

I knew Beauty then. Had Beauty been hiding all that while, beyond that veil of which Bergson speaks, "interposed between nature and ourselves, or rather between us and our own consciousness, a veil that is opaque for the generality of men, but thin, almost transparent, for the artist and the poet"? Had we set aside "those symbols of practical utility . . . which mask reality from us"? Was reality beauty therefore? And were not the extremes of art the obverse and reverse of the same coin?

I will not be metaphysical. The actual, the physical, fact was this only: that a mirror was placed on that further wall, in which, from our vantage, the whole stage was contained as a composition of a master in its intended and consummate frame. What strange man placed it there, if he knew its wizard virtue, if it enmeshes Beauty still in that banal theatre, I cannot

say. But "Look!" I whispered to my friend, "Look!" and I seized his arm. He was silent, and turning towards him, I found him gazing too upon that apocalyptic mirror.

For all there was of vulgar upon that stage and of pathetic, having passed through this transmutation, was rapt into the ether of perfect Art, where day is windless, night without mist; an ether removed from the confines of known dimensions, where Beauty is unconditioned by time, so that it endures more briefly than foam, more stolidly than granite. Here, when the girls of the chorus danced, it was with the rhythmic swaying of Egyp. tian votaresses or grasses under clear still water. But their lips were subtle, like the archaic maidens with plaited hair who smile so delicately in the small museum upon the Acropolis. The hair of the chief lady was massed with the marching gloom of Caravaggio, her movements were slow and sombre, like a tide. The futile figure of the leading man became immaculate, as a flower is in the dustless Alpine air; his lines swept with elegance and power like the bow of Paganini or the brush of Tiepolo. The wretched scenery put off its wretchedness. Not Toledo stood more solid to all the four winds. Not Marettimo in the sea northwestward from Sicily took the air more cleanly.

Upon that tawdry stage, distant from us by all the distance of the actual and false world, a buffoon had capered, red-nosed, froth on tbe stream of men. Here, in this mirror, he attained the terrifying dignity of the Comic Spirit, his mechanic face immobile like the mask of an actor in the theatre of Dionysius, facing now the impending tiers of Athens, now the laurelled brows of tbe Cod. It was tbe Comic Spirit which had inspired the enormous lungs of Aristophanes and given to the cheeks of Rabelais their rotund benignance. The sun was that clown's aureole, as it had been Fielding's and Meredith's. Was it not, indeed, sublimely comical that the blood-stream of Man should be a vaster torrent than the Milky Way and the sword hung in the scabbard of Orion should be a thing far frailer than a penny trumpet?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now