Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowHow to Read Books

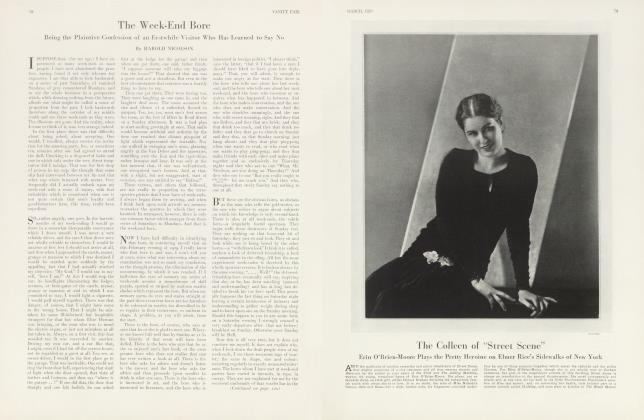

HAROLD NICOLSON

Why Telling the Truth About Your Literary Tastes Is the Only Good Course to Follow

ADVICE about reading books is a subject which must be approached with delicacy. No decent person likes to be told what or how to read. And yet it is a matter in which a little frankness, a slight absence of pretension, may possibly assist the uncertain and stimulate the weak. There are certain rules which can and should be applied. I trust that I shall be forgiven if I indicate such rules.

In the first place avoid being impressed by the recorded experiences of the eminent. There is no such subject on which the great manifest such duplicity as on this subject of their early reading. We are all familiar with the Great Poet who in childhood dragged the in folio Spenser from his grandfather's library and sat small and immersed under and in the Faerie Queene. This meandering and inconclusive poem is doubtless of great importance in the history of English prosody. There are moments, even, when those Spenserian stanzas elope with such consummate ease that they convey the impression of important poetry. Nor should I deny the charm of Spenser, an unhappy man, who, in that bleak tower of Kilkolman, struggled through dark ways.

BESIDES, he was a friend of Raleigh and Philip Sydney, and wrote some charming things on the subject of Chaucer. A desirable man, and not one whom I should wish to deride. I contend only that that long poem of his, with its reiterant melody, is not a poem which should appeal to any healthy child. And yet—take any autobiography of any leading poet, and you will find the bit about the Spenser folio dragged along his childhood. It simply isn't true.

I prefer myself some frankness on the subject of one's early reading. I prefer what Tennyson said to one of his more importunate admirers. "What," this sycophant had asked, "was the poetry which first, Lord Tennyson, revealed yourself to yourself?" The Laureate, in his muffler and his large and dirty hat, grunted. He paused to think. "My own," he thundered eventually, "at the age of five." I like that remark, mainly because it was strictly true. Tennyson as a child was obsessed, as are most intelligent children, by the problem of personal identity. He would toddle among the wolds of Lincolnshire, repeating "Alfred" to himself and again "Alfred." Shortly afterwards he evolved, or imagined that he had evolved, the line: "There is a whisper in the wind." Thereafter this formula came to mingle with his earlier incantation. "Alfred, Alfred. There is a whisper in the wind. Alfred. Alfred." That was the subsequent formula. I can conceive of no sequence of words which could have had a greater formative influence on Alfred Tennyson's poetry, or be more illuminating in regard to their eventual content.

Take the opposite combination of evasions. Byron, as is evident, was immensely and, until Don Juan, permanently affected by Chateaubriand. The earliest portrait of the Pilgrim of Eternity is evidently moulded upon the only then existing engraving of Chateaubriand. It represents the young, the very young, Byron landing from a boat, with his hair en coup de vent. Even his nose (not a very powerful feature in Byron's face) is given that wabblylook which we associate with the author of Le Genie de Christianisme. And yet, among all the many people and influences mentioned a hundred times in Byron's books and letters, M. de Chateaubriand is only mentioned twice. All this again is just not true. It is as big a lie, if you are Mr. Ruskin, to say that your literary taste has been moulded by the Faerie Queene, as it is a lie, if you are Lord Byron, to suppress the fact that you have been moulded by Chateaubriand.

Things do not work out that way. The fact is that a man is in general influenced by the books which first gave him a taste for reading. These books, in most cases, are not the great and good in literature, but some purely adventitious rubbish which happened to strike him at the age of eight, or again at twelve, or again at puberty, or when he went to Oxford. What is important is firstly that he learnt to like reading, and secondly that having absorbed this lesson, he came to discriminate. But the biographies of the great are as silent about the bad books they read and liked as they are silent about the good books they were made to read and did not like.

I AM fully aware myself of the books which went to form that exquisite literary taste which today gives me a certain arrogance and independence when talking to the illiterate. I can remember the pity and terror aroused in me by "Froggy would a wooing go." It was deeper and more soul-moving than any similar emotions subsequently aroused by Shakespeare, Sophocles or Ibsen. There was a picture of the event, a gullible and greedy duck, and the large spindle legs of the frog twitching downwards towards a gullible death.

I loathed that story and that picture. Fat and clumsy fingers would, when the page arrived, struggle to turn it over, to pass on to more agreeable subjects. The sense of tragedy, the conviction that such things were only permissible if accompanied by a happy ending, was born within me. Taste, in tragedy, was formed. Comedy also dawned for me in a form which; if I could fully remember it, would be pitiful and humiliating to relate. It was some parody of "The boy stood on the burning deck." It was about a boy who ate so much that he broke in pieces. I was so impressed by the wit of this rendering of Felicia Hemans that I copied it out for my father in place of the Sunday letter which on Sundays I dutifully and inkilly composed.

Fiction came to me in a gentler form. There was a book, which I read three times, called The Angel of Love. It was bound in blue and there was a representation of stars upon the blue cover. It made one feel good. It was all about consummate virtue in nursery life. Virtue, so far as I can recollect, triumphant. I loved that book. No work has had so profound an influence upon my development. Then there was Scott, whom my father wished me to like, and Dickens, who was my mother's special favourite. I loathed—I still loathe these authors. I read G. A. Henty and Merriman and Marion Crawford and Marie Corelli and Anthony Hope. These are the great masters to whom I owe my initiation to literature. And then later there came Wilde and Pater and Swinburne. And finally Beerbohm. All of these, except of course the last, are authors whom I condemn today. Now were I an important figure, and were I, as such, to be questioned regarding my early influences I should say, after a short passage about the large folio of Spenser under which (a tiny tot) I struggled from my grandfather's library—I should say that it was, that they were, Goethe, Shakespeare and Dante,—and then I should smile affectionately and add— "and, of course, Max."

THERE was a book also by Mr. Lewis Hind (or was it Mr. Louis Hynde) called The Education of an Artist. It was a soppy sort of book about a young man who strolled, all philistine, into the gallery at Antwerp and forty minutes later undulated out of that gallery a confirmed aesthete, having been converted by a little drawing of St. Anne visiting a Cathedral. Yes it was a very moving book. I had the pleasure, many years after, of expressing my gratitude to Mr. Hind (Hynde?); and, my word, he was surprised.

The main point, therefore, about reading is to read. The first thing to do is to make absolutely sure that you really do like reading. The thing is supposed to be, and often is, a pleasure: there is no possible reason why it should be elevated into a duty. You should begin by reading very ill-written books and those which your more literate friends decry. Well-written books often require some effort on the part of the reader, and if you are only just beginning, this effort is sheer waste of time. The test of whether you honestly enjoy reading is a simple one. If you leave your home and take your own book with you, it means that you are one of those who read sincerely. If, on the other hand, when you leave your home you rely either on the railway book-stall or on the books which you may, or may not, find there when you arrive, it means that you do not care for reading. If you belong to the latter class, all that I advise is never, in any circumstances, to discuss literature. If you belong to the former class there is much more to be said.

Firstly, read only what you honestly enjoy. In this rudimentary stage—when once, that is, you have passed my test of being a sincere reader—it is of no importance whatever what sort of book you read. If you like Mr. Aden's books (and they are far better than is supposed) then read them voraciously until the edges of your appreciation begin to fray. Then pass to something better; it would only be invidious for me to indicate the stages. It is important that you should not desert Mr. Arlen until you are honestly sick of Mr. Arlen. You must insist to yourself upon absolute moral rectitude, upon stringent intellectual integrity. Gradually you will find that Mr. Arlen, while titillating your emotions, does not satisfy your imagination or your mind. By this process you will arrive, let us say, at D. H. Lawrence or Virginia Woolf. It would be a fatal mistake to tackle To the Lighthouse while you were still under the spell of the insidious and highly talented Mr. Arlen. That would be insincere. Watch your own development loyally, and do not be tempted to betray it by the sneers and gibes of others less illumined and honest than yourself. Remember also that there is no bore on earth more insufferable than the sham-culture— (or indeed the real-culture) bore. Keep your head.

(Continued on page 102)

(Continued from page 55)

Having attained to the summits of literary acumen, you will then proceed to read books which are not only very difficult to read, but which elude both understanding and memory. When this stage comes, you will begin to think about taking notes. It is a mistake to annotate the books of your earlier stages. You will be ashamed, when having reached stage five you idly turn, in some guest's bedroom, the pages of some relic of stage two, to discover that you have marked and annotated one of Mr. Arlen's earlier novels. You will blush as you read your own indelible pencil notes— "Comme il connait bien le cceur d'une femme"—that is what you will have written on page 422 of The Green Hat. And when, after a morning spent on analysing Bergson, you come across that pitiable annotation you will, as I have warned you, blush. On the other hand, and especially in the later stages of culture, it is an excellent habit to make pencil notes. These should be conducted on some system such as will demonstrate to subsequent readers of the book (of your copy of the book) how bright and studious you are. It is no use marking the thing, and it is dangerous, unless you take very long about your thoughts, to make comments. The best thing to do is to scribble a sort of guide or index at the end of the book, which gives to your errant markings a certain conformity and meaning. This index, however, should be of a very personal nature, and not understandable to the uninitiate. My own books are scored with such annotations. I do not write "very feeble and cheap" in the margin of a particular passage. I merely mark the thing with a neat but non-committal line against the side. And at the end I put "F. and C. pp. 23. 58. 69. 78. 92. 105. 114.", and so on. Nor do I confine myself to denigration. "G.B." I put, "pp. 54. 98. 224. 669 9956. 10456 24378." "G.B." means "Good Bits", just as "B.B." signifies "Bad Bits" or "l.o.s.o.p." "Lack of sense of proportion." Obviously, all my annotations cannot thus be rendered in cypher. On occasions, and for convenience of future reference, I have to render my index more explicit. "Surrey", I have to write, "incomprehensible liking for" or "Irritability, sensitiveness to other peoples." In the end this index is not only useful but impressive. I have only to look at my fly-leaves in order to recollect what I thought of the book at the time I read it. But I repeat, is not a method to be adopted with those books of which, ten years later, one is likely to be ashamed. I am very glad, when I think of it, that I never annotated my copy of Dorian Grey.

There is also the question of the distribution of one's reading. I do not believe very much in those people who read four books at a time. But I do believe very thoroughly in those people who read two books at a time. Only they must be different sorts of books. You might read, for instance, To the Lighthouse (Q. S. 54. 65. 87. 98. 345. 674. etc.)—Q. S. by the way means "Quote style"—concurrently with Edgar Wallace. That indeed would be a wise thing to do. But if you read To the Lighthouse concurrently with Joyce or Wyndham Lewis you would be committing a very regrettable mistake. There is a physiological justification for this contention. Mr. Edgar Wallace (bless his heart) is an absorbent whose welcome works serve as a counter-irritant, drawing the surcharged blood from one lobe of the brain to another lobe. It is far better to read a detective story when one is exhausted than to go for a long walk in the Park. On the other hand to read two books at the same time, which affect the same frontal lobes I is to create conditions in which cerebral inflammation may occur, or merely fuzz. There are some books also, some verbose but valuable books, such as William James, which have to be analysed in a note book. But that is a very late stage, and I fear that the thing is pretentious in appearance, and should be secretive in practice.

Then there is the question of foreign literature. That is a terrible question, and one which it is safer to avoid. I knew a woman once, she was a German woman, and she spoke French like M. Claudel, and English almost as excellently as I do myself. Her mastery of these languages was only equalled by her mastery of their literatures. She knew all about Donne and Amiel, and John Clare and Tristan Corbieres. She also knew Italian and was excessively tiresome about the early poetry of.well let us say Azeglio. Then one day she asked me about Sologub. I said I had read some stories of his which had much impressed me. She asked me whether I had read them in Russian. I said that I had read them in English. "Oh" she answered, sinking back among the cushions, "I think it is a crime to read the Russian masters except in the original." That is a thing, that is an enormity, which you should be careful neither to indulge in nor commit. It humiliates. It may well be true and very clever, but it humiliates. So be careful not to snub people about Proust (he is far better in English) and be careful not to say that you prefer the original version of the Sonnets from the Portuguese. In fact the best lesson on how to read books is an ethical lesson. Tell the truth.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now