Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Nowbrownstone blues

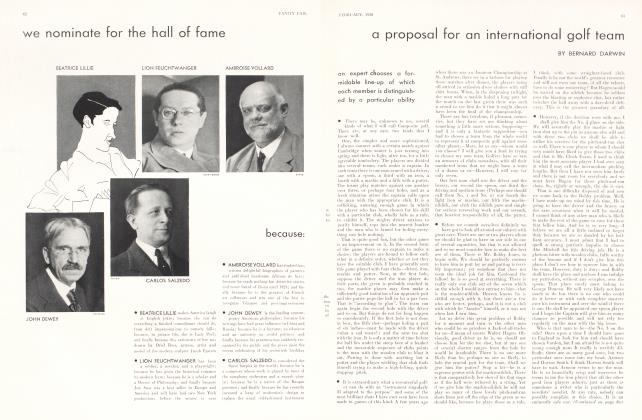

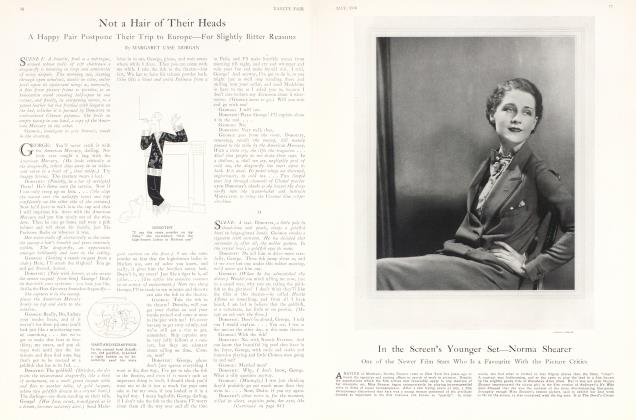

MARGARET CASE MORGAN

a husband seeks over all the world the answer to a question and finds it, after many years, at home

Evelyn Ewing's husband got up and turned the flame of the gas-log a little lower. Its pitiless blue light had fallen directly on his wife's face, flaring coldly on the swift, despairing lines of her mouth as she talked; and he felt dimly that Evelyn's mouth, even thinned and sharpened by unhappiness as it was now, was still too lovely to dwell in any but the kindest shadows.

"It isn't," she was saying desperately, "that I am in love with anyone else; only I don't seem to love you any more." Her hands, stiff with distress, relaxed hopelessly; and the diamond he had given her trembled into tiny splinters of fire. "I—I hate the way you hold your head on one side when you look at me, and the way that dreadful high, stiff collar sticks into your neck when you do it. I detest that cat's eye scarf-pin you always wear, and that trick you have of opening your mouth a little when you start to speak, and holding it open thoughtfully for a second before you say anything. And I loathe myself for feeling the way I do, because you're so good to me . . . you're such a good man, Charlie!"

Her voice thinned to silence, and for a little while there was no sound in the dim room. Outside, in the blue November twilight, the crisp staccato of a horse's hoofs rose on the air and died away down the street.

She was so lovely, he thought, looking at her now as she sat a little forward in her chair, the fire-light dissolving in pools of blue shadow upon her hair and at the base of her throat . . . just like one of the drawings of the Gibson girl, he had often told her. He realized now that she had probably found that dull, too. But he had believed that he was making her happy. He was, of course, older than she —but only seven years older; and for a young man of thirty-six his position in New York, even in these increasingly brisk days of the early nineteen-hundreds, was socially and financially comfortable. Their house in Fiftieth Street was one of the sturdiest in all that complacent brownstone row; their winecellar was liberal and chosen with taste, and he had always thought that their small dinners went off very well. "Mr. and Mrs. Charles Ewing entertained . . ." He liked the sound of that.

Evelyn had an upstairs sitting-room of her own—a room sleek in warm brown velours with an occasional froth of Nottingham lace on the chairs and at the windows, the room where they were sitting now. When she shopped or went driving it was in a victoria with a coachman in purple livery, and she had charge accounts at Hughes' and at Lichtenstein's. In the five years of their marriage, she had seemed contented; but lately he had known that something was wrong, that there was, somehow, a subtle and difficult discord in their life together which he, in his simplicity, was unable to understand or to dispel.

What is it that you want, exactly?" he asked. "A divorce?" The word, when he had spoken it, seemed to return painfully to his throat, to settle there, hard and cold.

"I want whatever will make you happiest," she told him miserably. "I'm very fond of you, Charlie."

Suddenly he was conscious that his lips were forming the small, thoughtful circle, preparatory to speech, which had irritated her; he closed them firmly until he should have arranged the words in his mind.

"Of course, you may get over this," he said quietly, then. "You may not always feel as you do now about wanting to leave me. Supposing I were to go away for a while—I can afford to. I could go abroad, and you could say that it was a business trip and that you hadn't wanted to leave New York now, just as the season is beginning. You see, there wouldn't be any gossip about it then. . . ." He was speaking slowly, sensibly, trying not to yield to the terror that inwardly possessed him.

"I'll deed this house to you immediately," he went on—and thought at once that it sounded too noble, a little pompous. "Of course, you'll have to pay the taxes and the upkeep. But I'll make arrangements at the bank . . . then, if you still feel, at the end of a year, that you want to leave me, I shall know that you're provided for. If—"

"Charlie—you're so good . . ."

He looked surprised. "No," he said, mildly, "I guess I'm just doing what I ought to. You know I love you, Evelyn. And if you should change your mind about leaving me . . ." The hope beat its way up into his heart, looked desperately out of his eyes as he watched her. She had risen, and was bending over a bowl of red roses on the table, her slim, unhappy fingers brooding among their stems. She shook her head slowly.

"It isn't a thing I've decided suddenly, Charles," she told him, "and I don't think I'll ever change. But if I ever do . . ." She smiled at him, a smile bright with pity and a helpless desire to comfort him. "If I ever do, Charlie, I'll let you know—and I'll be waiting here for you, dear."

He stood up. "Well . . . I'll go down to the Club now. There's no use in prolonging all this. You can send my things down there, and I'll have them taken on to the boat when I sail."

He wanted to get away. She was so beautiful standing there, with the cool, frosted blue of the dusk lighting the windows behind her, and a scarlet rose in her hand. She came and

stood by him, suddenly eager and pitiful. "You won't be too unhappy?" she begged. "There's so much excitement in life—so many things to see, and to laugh at and to love; and that's what I mean to find. But I want you to find it too, to let a little gaiety into your own heart."

She paused desperately. "We can't be happy together—and I'm sorry. But don't let it spoil our lives, don't take that bitterness away with you. Try to forget me—and try to have a good time, Charlie!"

To have a good time! He thought, My God, I hope she isn't going to give me that rose. When a woman sends her husband flying out of her life it's rather poor taste, he reflected with a sudden bitter humour, to pin a rose to his coat-tails. But there it was . . . smooth and fragrant, a cool curve of crimson velvet against his palm.

In the hall, he took his hat and coat from his own particular hook on the hat-stand with the carved antlers and the mirror that they had bought together. Probably she hadn't meant to give him the rose at all, he decided; she had simply been holding it when she gave him her hand for the last time. ... He put it in his pocket hastily; no use being sentimental about it.

He stood for a moment with his hand on the door-knob. The atmosphere of the house closed down upon him like a sheltering hand. He could almost feel it holding him, pushing him back ... it was his home.

Then he turned up the collar of his coat, slammed the door behind him, and ran down the brownstone steps into the chill dusk.

"Try to forget me . . . try to have a good time, Charlie!" The futile words followed him miserably, echoing through the staccato accent of Paris, the pattering mist of Scotland, the liquid murmur of Venice. He hadn't, at first, wanted to try. He didn't know how to be gay, he didn't know anybody who could teach him gaiety. He had, it was true, a bowing acquaintance with a fairly large number of people—but it seemed to him that scarcely had he lifted his head from the rather courtly salute which he always gave them, than they were gone . . . fluttering away from him like brightly-coloured leaves in the wind. He was often alone.

The cable was weeks late in reaching him— it had followed him from Paris to Cairo, and back to Paris again. Evelyn had, on the train going to Hot Springs, caught a cold which developed in a few days into pneumonia. . . . He remembered how, only two years before, he had left her radiantly poised on the threshold of freedom, of adventure—unsuspecting that what lay beyond was not brilliance, but a shadow. . . . After that, his feet, which had never known how to dance through life moved, still more slowly, and beside him walked the twin specters of his loneliness and of a doubt that never left him. Had Evelyn thought of him at the end, when it was too late? What, in those last tortured hours, had been in her mind? Had she loved him? Had she, perhaps, been sorry. . . .

Continued on page 90

Continued from page 46

He would never know; and he would never stop wondering.

It occurred to him now, as he sat alone at a little table at Colombin's in Paris, that twenty-five years abroad, most of it spent in France, would make a boulevardier out of most men; it hadn't made one of him. He could see his reflection in a mirror on the opposite wall, and suddenly he knew that nothing could have kept him from looking, at sixty, exactly as he looked now; a small, plaintive sort of man whose hair was brushed carefully upward over his ears in gay, hopeless little points with a bravado that was entirely lost in the downward curve of the shoulders below them. He sighed, and ordered a cup of Ceylon tea.

There were several people in the room whom he knew slightly, he reflected with a certain amount of pleasure, looking around him. They had nodded to him, smiled briefly, as they passed his table; but he wished that one or two had stopped to speak to him. They produced in him, these bright, enameled Americans, a melancholy curiosity about the country which he hadn't seen for twenty-five years. There had been nothing to take him back—his roots, his home were in Europe.

Abruptly, he knew that that wasn't true. He had no roots anywhere, no home except—he thought of the house in Fiftieth Street, the tranquil, sturdy brownstone house which he had deeded to Evelyn twenty-five years before.

When the waitress brought his tea, he asked her for a Paris Herald with the list of steamship sailings in it.

Another November twilight, cool and brittle, shrouded the substantial rows of brownstone in a mist so thickly blue that Charles could almost feel the texture of it against his face. He stood on the sidewalk in front of the house that had once been his, and decided that he was, after all, a sentimental man; for he was almost trembling with the excitement and the longing that was in him. . . . There was a millinery shop next door—that was why he had not recognized the house at once; and of course, they had taken the carriage-block away from the curb —that was only to be expected. He had thought of ringing the bell and asking the present owner—whoever he was— if he might come in and look around a little, explaining that he had once lived here; but now he saw that people were going in and coming out of the house—little groups of men and women silhouetted, in a sharp flurry of movement and laughter, against the thin fan of amber light from the briefly-opened door. They were passing —curiously enough—through the areaway, and using the basement entrance.

Hesitantly he descended the two brownstone steps into the area, and found himself, with several other people, pressed against the basement door. He could smell the faint odour of violets on the coat of the woman in front of him. A thin brown hand opened the door a crack, then widened the crack with a gesture of professional hospitality; the people crowded inside, laughing and crying "Hi Jo!" as the men dropped their hats and coats on the walnut hat-stand in the hall. Charles didn't hear them. He was looking at the hat-stand ... it was the same one, with the carved antlers and the mirror, which he and Evelyn had bought together. The hook which had been his now bore a grey derby and a polo-coat; Charles removed them carefully to another hook, and hung his own hat and coat in their place.

The stairs wound upward into a vast canopy of muted sound . . . He mounted them slowly, and turned toward the room that had been Evelyn's sittingroom. In the doorway, he paused, his eyes eager upon the fireplace where they had sat on that last day, upon the windows against whose frosted blue he had last seen her. But the fireplace now held a contrivance of electrically lighted coals, a bright contortion of false, busy flames; and the windows were muffled and blind in rich draperies of crimson velvet, mysteriously embroidered in coronets. Curiously, he looked around the room. Small tables, sleek with linen and silver, covered the floor thickly, almost touching one another; upon the bland, plaster surface of the wall trellisses climbed, bearing with them a profusion of artificial vines quivering delicately beneath a glory of red cotton roses. And here the atmosphere became definitely Spanish; for, as the roses neared the top of the wall, they grouped themselves in hopeful clusters beneath small, imitation balconies, and there waited in vain for the languid Senorita who would surely never smile above them.

Charles found a vacant table, and sat down at it. He ordered coffee. The waiter hesitated.

"Nothing to drink, sir?"

"To drink? Oh ... a Cointreau."

This was a speakeasy, then. This room was a parody of that other room where Evelyn had stood—had said; "If I change my mind, I'll let you know . . . and I'll be waiting for you."

Once more he wondered, painfully now, whether she had ever changed; whether at last, when it was too late, she had wanted him—had, perhaps, loved him. . . . The doubt ached in his mind and heart.

"Try to have a good time, Charlie," she had said. And then he had found the rose against his palm—that intolerably dramatic rose that he hadn't wanted.

He drank some coffee, and looked vaguely at the people around him. He looked at each one for a long time.

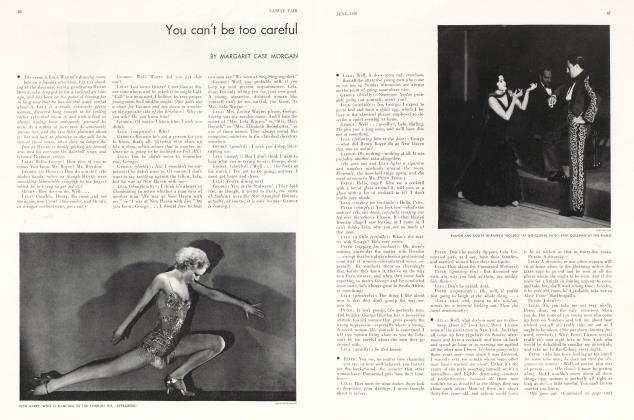

"It's tough, when they keep you waiting, isn't it?" The question, repeated in a high, friendly voice, made him turn, finally, and look at the girl sitting at the next table. She was smiling at him out of eyes brilliantly starred with mascara, and the hand that held her cigarette in an onyx holder was tipped with scarlet nails; but the line of her hat, fashionably raised high on her forehead, was definitely youthful, and there was a simplicity of youth in the cheerful curve of her mouth and chin.

"Yes, indeed," answered Charles tentatively; then added; "I'm not waiting for anyone, though. I'm alone."

Continued on page 100

Continued from page 90

He didn't know why he had told her that; but it was somehow a relief to say it to someone, to admit, even so casually, the fact of his loneliness.

Her hat rose alarmingly with the sympathetic curve of her eyebrows. "You are? Well, why don't you come over and sit down with us? I'm waiting for my friends."

He had no definite intention of accepting, but the friendliness in her eyes compelled him. He went over and sat down, struggling with the chair, which was pushed too snugly between the table and the trellis on the wall.

"I'd have a cocktail if I was urged," she said pleasantly, after a pause.

The cocktails came, little amber pools of cheer with a cherry at the bottom. She hoped, she said, that he wouldn't think she was the sort of girl who spoke to strange men . . .

"Surely, my dear child, there's no harm in talking to an old man like me," protested Charles, pleased. He ordered two more cocktails.

Her name was Sally.

Charles, finishing his cocktail thoughtfully, meditated upon a tremendous plan; he would ask this cheerful, kindly girl and her friends to take dinner with him here, as his guests. Sally, confronted with the scheme, brightened with approval.

"Why, we'd be very pleased, I'm sure! Here they are now . . . that's Pauline, and those are Jim and Bernie. Bernie is my friend," she added in an intimate whisper.

She broke the news of the dinnerparty to them. Pauline was languidly acquiescent, and the two young men, after exchanging a single, dubious glance, allowed themselves expressions of acute relief as they sat down.

Charles smiled amiably upon them, enchanted with his role of host. These young people, he felt obscurely, were his friends; they admired him, he was important to them. In the pleasant hilarity of this company he could almost forget the sorrow and the doubt that, in his loneliness, had haunted him. He ordered the dinner with care and inquired, after a slight pause, whether champagne could be procured.

"Champagne! I guess so," said Sally, adding regretfully, "I never had much experience with anybody that wanted to know."

Charles commanded two quarts of Lanson, 1921; they were brought, suave and golden in glittering beds of ice, and Sally sipped hers with closed eyes.

"Gee," she breathed respectfully, setting down her glass, "I'll say you're the world's original Good-Time Charlie!"

The others raised their glasses and toasted him indulgently.

"To Good-Time Charlie!" they cried, their mouths eager over the wine. The semicircle of faces blurred in the flashing, amber blaze of those lifted glasses; they seemed enormous, intolerably bright as they drew nearer to him, closed in upon him.

Try to forget me—try to have a good time . . . Charlie. . . . He stared at them.

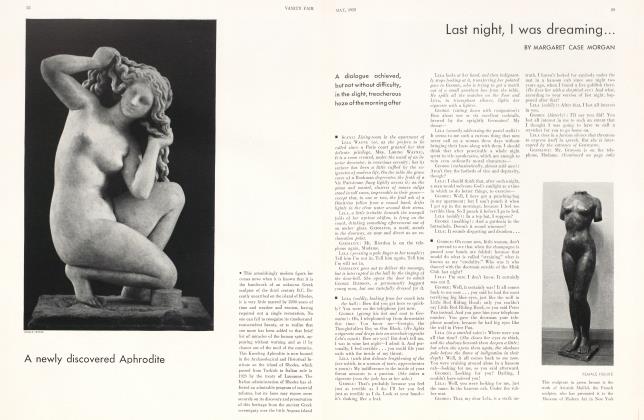

Then he pushed back his chair, knocking violently against the trellis on the wall. The vines rattled and an imitation scarlet rose, its petals dim with dust, floated down and rested on the table before him.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now