Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

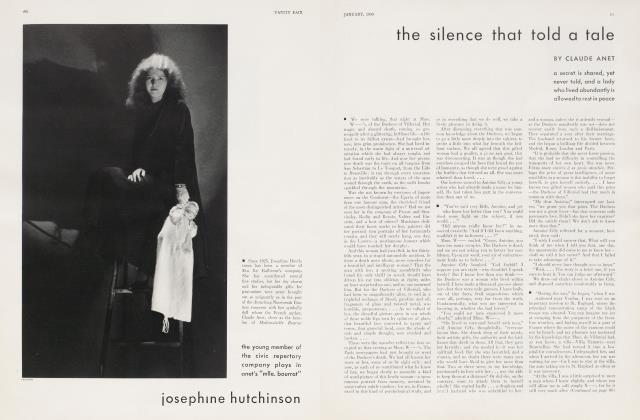

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Nowpetrolini, an acting genius

ALDOUS HUXLEY

reflections on theatrical themes, particularly actorproof plays and one playproof actor in particular

The place is Rome; the time, an hour after sunset; the problem, what to do? The really conscientious tourist will have, of course, no doubts. Remembering Chateaubriand and Mme. de Staël, remembering Lord Byron and Shelley and Nathaniel Hawthorne and all the other romantic sight-seers, whose literary ghosts still faintly "squeak and gibber in the Roman streets," he will leave the hotel as soon as dinner is over and walk reverently past the Forum to where, beneath the moon and above the arc-lamps, the Colosseum stands, smooth and curving, like some enormous sea shell, left high and dry by the receding tide. There, in the shadow of the toppling walls, he will meditate, he will muse, he will think all those high-class and melancholy thoughts which tradition decrees that one shall think amid the wreckage of Ancient Rome.

This, I repeat, is what the conscientious tourist will do. But I am not a conscientious tourist. When night comes on in Rome, I do not go to see the Colosseum by moonlight. I go to see Petrolini by lime-light. With all due respect to the conscientiously romantic sight-seers, I consider my evening better spent than theirs.

Yes, better spent. For Petrolini is alive, a consummate actor and a man of genius.

Petrolini can give me something new, something that is not myself, something I could not have invented or even imagined the existence of. For Petrolini, as I have said, is a man of genius—one of the great comedians of our time—and the essence of a man of genius consists precisely in the fact that he does things which are unforeseeable and finally inimitable. His activity is sui generis and can be fitted into none of the ordinary categories.

An ordinary piece of acting—or, for that matter, any work of art not of the first rank— brings me hardly more than an empty ruin, like the Colosseum, could bring. For the ordinary actor, the merely adequate artist, tells me nothing I did not know already. True, it is not I who fill him with life, as I must fill the moonlit amphitheatre. But the life that is in him is of a kind with which I am perfectly familiar. He can do nothing which I myself could not do or, at any rate, think of doing. The second-rate actor is not an empty shell; he possesses an autonomous personality. But it is the sort of personality which the intelligent spectator already knows; observation and introspection have made him familiar with it. A work of art is simply the fossil imprint of a personality. (In the case of the actor, the imprint is not fossilized in a nonpersonal medium; it is made directly by the artist on his audience.) A work of genius is the imprint of a personality so extraordinary that nobody but the maker could conceivably have left the mark or thought of its form. A work of the second rank is one which many people might have produced in substantially the same form; the imprint of any secondrate personality has a strong family likeness to the imprints of other contemporary second-rate personalities. For the intelligent spectator there is nothing fundamentally new in a second-rate performance. (There may, of course, be superficial novelty, just as there is novelty in the morning's paper; but the newness of news is of a different order from the radical and fundamental newness, even after centuries, of a Mozart, a Chaucer, a Giotto.) The second-rater gives him nothing of which he does not already know the substance, nothing of which, in the appropriate circumstances, he might not have thought himself.

Whenever I go to see Petrolini, which I try to do, religiously, whenever I am in Italy, I see something entirely new, entirely not myself, entirely beyond my powers of invention. His performance enriches me with such wealth as only an extraordinary work of art can give. He even reconciles me, temporarily, to the theatre, renewing in me an old passion which the abhorred practice of dramatic criticism has all but completely eradicated. "If only every evening's entertainment could be like this!" I said to myself, after my most recent visit, some few nights since, to Petrolini's shrine.

Parenthetically, but relevantly, the memories of other theatrical entertainments intruded themselves at this point. I recalled performances of Shakespeare, inept as only performances of Shakespeare can be inept. And yet, so long as the actors remembered their lines and uttered them audibly, I had enjoyed these performances. I remembered Tchekov's Three Sisters, given by a semi-amateur and wholly incompetent company, staged by an affected imbecile, produced with extreme stupidity. A hopeless performance. And yet I had enjoyed it. The actors knew their words and the words were unmistakably Tchekov's. In these cases and in only too many others like them, the play had given me pleasure in spite of the actors, the scene painters, the producers. It would obviously have given me much more pleasure if these had been competent; but it had, in any case, been able to triumph over their incompetence.

From these two sets of memories—my memories of Petrolini on the one hand, of touring-company Hamlets and play-society Sea Gulls and Wild Ducks on the other—I drew the following conclusions. First, that really good plays are almost completely actorproof, producer-proof and designer-proof. Secondly, that really good actors are almost completely play-proof; also proof against bad acting by their fellows and bad stage management. And, thirdly, that good producing and good scene painting are not proof against bad plays and bad acting, or even against moderately good plays and competent acting unrelieved by any admixture of genius.

These conclusions are certainly true so far as I personally am concerned. When I go to the theatre I go to be enriched by contact with some extraordinary and (by me) uninventable, unforeseeable personality. This contact is either with the fossil imprint of the personality in a play, or immediately with the .living man or woman performing before my eyes. It is only when I make such contacts—contacts with the fundamentally new, the other than myself that I feel that it has been worth while to go to the theatre (though of course, like everyone else, I can take a passing interest in the superficially new and exciting in art, just as I can take an interest in the morning's politics and murders). If the fossil imprint of a personality in a play is extraordinary, I can ignore the ineptitudes of the actors. Or if one actor is a genius, I am ready to put up with the second-rateness of the others. In no circumstances do I get any solid satisfaction from mere efficiency of dramatic craftsmanship or from mere well-trained excellence of team-work. Dramatic craftsmanship is something that can be learned; professors give lectures on it; I myself could take a course in dramatics, if I wanted to. And as for team-work—why, if I want to see good team-work, I can go to Buckingham Palace at eleven o'clock any morning of the year and watch the changing of the guard. A SergeantMajor of Grenadiers can create a more perfect ensemble than any producer. There is a certain pleasure in seeing a group of people functioning together in well-trained harmony. In certain artistic circumstances this pleasure can become intense. Thus, a ballet can be delightful; it can be, in its own sphere, as fundamentally new, as unforeseeable, as much of a work of genius, in a word, as a play, a poem, a symphony. But a play is not the same as a ballet. A play is an affair of human characters; it is only very incidentally pictorial. In a very crude, inadequate way certain psychological ideas can be expressed in terms of pictorial and choreographic symbols. But for all the finer shades of expression only words and the intonations and gestures of the individual actor will serve. The producer is powerless to modify either of these. He cannot change the words of the play, transforming it from a bad play into a good one; and though he can teach the bad actor to be less bad, the competent actor to be more competent, he cannot miraculously turn the bad or the merely competent player into one of those inspired, heaven-sent creatures, like Petrolini or Charlie Chaplin, like Duse or the elder Guitry; one of those extraordinary artists who can re-create reality so as to make it seem incomparably more real than the model they are supposed to be imitating. Nor will twenty second-rate actors trained to the highest pitch of efficiency and working together like a team of foot-ballers succeed in making a bad play tolerable and even admirable, as one actor of extraordinaiy personality, even though accompanied by nineteen badly trained imbeciles, can always do.

Continued on page 88

Continued from page 54

During the last few years all the accessories of drama, by which I mean the scenery, the lighting, the instillation into actors of the team spirit and the team technique, have received an enormous and, it seems to me, exaggerated amount of attention. The old system of having one star and ignoring all the rest has been discredited. All the emphasis has been laid on production. What is the reason for this state of things? To begin with, there has been a great increase in the number of theatres with no corresponding increase in the number of actors of genius. Managements have therefore made a virtue of necessity and preached the superiority of the good all-round performance to the shoddy performance tempered by genius. This doctrine is, of course, entirely in accordance with the current democratic and humanitarian ideology. The fundamental article in the modern creed is that one man is as good as another and that anything that can't be achieved by education can be achieved by spending money on ingenious apparatus.

Theatres are accordingly filled with ingenious apparatus and highly educated actors. With results which, at any rate for me, are disappointing. I go, I admire the scenery, the lighting, the high average level of accomplishment among the actors— admire and, unless the play happens to be stimulatingly good, am bored. For an hour of an actor of genius, I would joyfully sacrifice all the good production, the fine sets, the modern lighting, the meritorious team-work, which are the boast of the "advanced" theatres at the present time. Others may have that; Petrolini is the man for me.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now