Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now"Murder is the matter!

EDMUND PEARSON

A mysterious encounter between a money lender and a dauntless British Major has evil results

Mr. Pickwick knew an old man who said that the rooms in the Inns of Court were "queer old places"—odd and lonely.

"Not a bit of it!" said a sceptical friend.

Then the sceptic, who lived by himself in one of these rooms, died one morning of apoplexy, as he was about to open his door. Fell with his head in his own letter-box, and lay there for eighteen months. At last, as the rent was not being paid, the landlords had the door forced, "and a very dusty skeleton in a blue coat, black knee-shorts and silks, fell forward in the arms of the porter who opened the door."

Years after Mr. Pickwick's adventures had ended, entrance was one day forced into another queer old room in a London house, and, with a tremendous clatter, out tumbled another skeleton, of a still stranger sort.

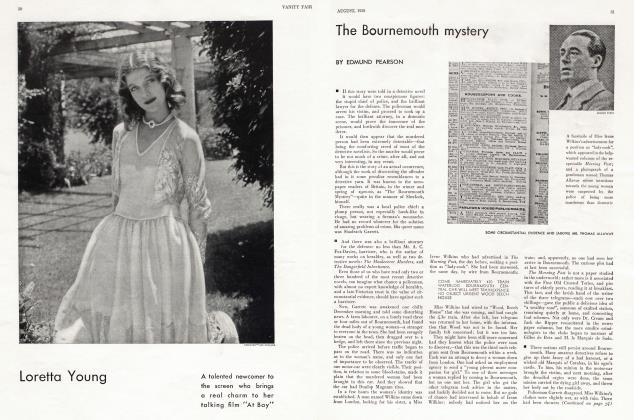

The noise it made was not heard in America, since we were completely absorbed, that summer of 1861, in the first battle of Bull Run. The story would be forgotten in England today, were it not for the admirable essay published seven years ago by the late Sir John Hall, Bart. This gentleman is respected by all those who appreciate scholarly descriptions of curious events. It is probable, however, that of all who see my retelling of the tale, only experts like Messrs. Alexander Woollcott and S. S. Van Dine, will be familiar with Sir John Hall's work. And as it has been solemnly asserted, in print, that the names of both Mr. Woollcott and Mr. Van Dine are but pseudonyms for the one which stands at the head of this article, the circle is very much narrowed. So I feel moderately safe in going ahead, especially as I have unearthed one or two details on my own account, including the portrait which decorates this page.

Toward noon of a day in July, in that far-off year, Mr. Clay, the manager of the Catalonian Cork-Cutting Company, was in the rear of his premises in Northumberland Street, London. He heard two pistol shots from within the house; one shot following the other at a fiveminute interval. He paid no attention, since he knew that one of the residents of the house had, for a month past, anticipated Sherlock Holmes in the eccentric custom of indoor pistol-practice.

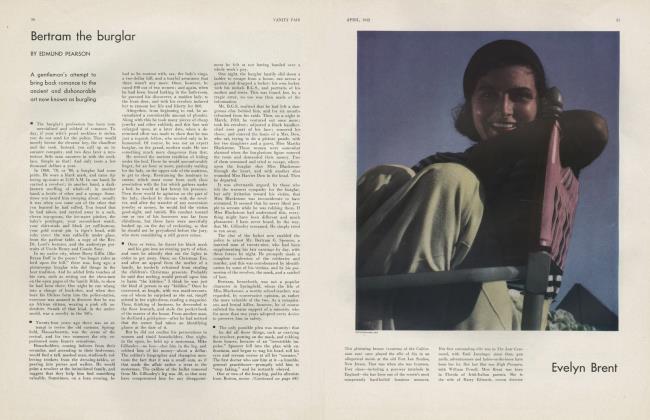

After a few minutes, a rear window on the second floor was opened, and there appeared the hero of the story. His conduct, his accoutrement, and some of his speeches, have always recalled to me those half-demented and curious persons who flit through the novels of Mr. G. K. Chesterton. He was a man in his forties; wearing, I think, sidewhiskers, and carrying in one hand an umbrella, in the other, half a pair of tongs. He put one foot on the sill, and seemed about to jump twenty feet or more into the yard.

This horrified the Catalonian cork-cutter, not only because the stranger's face was covered with blood, but because of the flag-stones and an area, with iron railings, directly below the window. He adjured the bearer of the umbrella, in the name of God, to do nothing desperate, but to tell him what was the matter.

"Murder is the matter!" replied the gory one, and continued his preparations for a desperate leap.

Mr. Clay sent one of his employees for the police, and ran indoors to try to get into the second-floor apartment. While he was banging at the locked doors, he heard glass breaking, and on looking out again, found that the mysterious person had jumped into the yard; fought off a workman who tried to stop him; clambered over a high wall into the next yard —still armed with the umbrella; gained an alley between the houses; and made his way into the street.

Here he was surrounded by a group of people who had come running from various directions. He complained that some one who lived at Number 16 had tried to murder him. One of the men in the street must have secured the umbrella—perhaps while the wounded man was adjusting his cravat, or brushing off his clothes—for the stranger asked for the umbrella again, and said that he must be getting to his office. This, in spite of the fact that he had lost his hat; had a terrible wound in the back of the neck; another, which was bleeding freely, on his cheek; and that both his hair and whiskers were singed.

Duty was evidently the keynote of his character. He was an officer and a gentleman, and to introduce him by name, he was Major William Murray, late of the 10th Hussars, but a total stranger to all in the street. As it will appear presently, deception was in his eyes a far more grievous offense than personal violence, and to him unsportsmanlike conduct seemed the blackest of sins.

A man in the crowd reasoned with him about going to his office.

"You are badly wounded," said this one.

"Am I?" replied the Major.

"Indeed, you are fearfully wounded."

Then the Major remarked:

"It's that damned fellow upstairs—Grey."

"There is nobody named Grey in that house," the man returned. "But if you mean the man I saw you go in with, about half an hour ago, his name is Roberts."

Then, at last, the Major allowed a faint note of bitterness to creep into his tone.

"He told me," he said, "he told me, that his name was Grey."

Meanwhile, much was going on in and about No. 16 Northumberland Street. The occupants of that and nearby houses had all heard the pistol shots, and one of them had heard other noises—as if someone were beating a mattress. But no one gave much thought to the reports, since they all knew the habit of their neighbour, Mr. Roberts, of amusing himself by target practice. Roberts was, by profession, a solicitor; actually he accommodated people by lending money. This he did at no great disadvantage to himself,—his idea of a proper rate of interest being 133 1/3%, per annum.

Inside the house, during the talk on the street, was a Mr. Preston-Lumb, an engineer. To him came young Mr. Roberts, son of the money-lender.

"Oh! Mr. Lumb," he cried,—forgetting, in his excitement, the glories of the hyphenated name, "Oh! Mr. Lumb, some one has been and murdered Father!"

Thus, at last, we learn the real origin of the remark which Miss Lizzie Borden called up the stairs to Bridget Sullivan, on another warm and sanguinary noon-day, many years afterward.

Meanwhile, the man in the crowd, and most of the crowd, too, were escorting the wounded Major, first to a chemist's for immediate relief, and then to a bed in the Charing Cross hospital.

Continued on page 94

Continued from page 51

The police, by means of ladders, at last effected an entrance to the rooms of Mr. Roberts. The officers looked at an amazing sight. The rooms were elaborately over-furnished in the French style of the period of Louis Philippe. Brackets and shelves were ornamented with statuettes and bric-a-brac, under glass covers. The floor space was crowded with ormolu tables and boule cabinets. Everything in the room was filthy with dirt and dust—the thick, black encrustation which follows years of neglect.

In the front room the ornate and dirty furniture was little disarranged, but the other room showed the marks of a terrific fight. There were splashes of blood on the walls, and a shower of drops of blood on the glass covers over the ornaments. In places, the room looked "as if a bloody mop had been trundled round and round."

Near the wall in the front room, his head a shocking mass of wounds, lay the owner of all this: Roberts, the money-lender. He had a dozen or twenty injuries, any one of which looked as if it alone should have been fatal.

He, also, was taken to the hospital, where, to the astonishment of the surgeons, he lived for six days.

Young Roberts was brought to see Major Murray, but his name meant nothing.

"What Roberts?" said the Major.

"Why, the son of the Roberts who shot you," was the reply.

Then the exasperation of Major Murray burst forth again.

"Why, damn him," he said, "he ought to be hanged for shooting a man on the ground!"

To the sporting Major, especially at a time of the year when the thoughts of all Englishmen were dwelling upon the approach of the grouse season, it was scandalous that Roberts had not flushed him before firing.

Since Roberts died without giving any reason for the fight, and since it was a mystery to Major Murray, the police continued to search the rooms for an explanation. At last, as in a detective story, they believed they had found it in a few marks on a bloodstained sheet of blotting paper. Holding this to the mirror, they deciphered the name "Mrs. Murray".

The inquest was held ten days after the fight. The so-called Mrs. Murray appeared, heavily veiled. When she lifted this veil, she disclosed "the features of a remarkably pretty woman" of about twenty-five. Her name was Anna Maria Moody. Seven or eight years earlier, she had left her family "to live under Major Murray's protection." When her baby was born, she was embarrassed for funds, and was unwilling to ask for more money from the Major, who, although a bachelor, was "under heavy expenses."

Continued on page 100

Continued from page 94

Someone told her of Roberts; she went to him, and found him willing to lend her £15, provided she signed a three months' note for £20.

She had never been able to pay the debt, but had continued to make quarterly payments of £5 as interest. Roberts had tried to make love to her, and offered to release her from the debt if she would leave Major Murray and go to Scotland with him.

The Major gave his testimony in the hospital ward; his throat bandaged, and his neck too stiff to let him move his head.

Roberts had accosted him in the street, introduced himself as "Grey", and offered a loan of £50,000 to the Railway Palace Hotel, of which project the Major was a director. The two men went to Roberts' rooms, where the host left his guest alone for a few minutes. He came back, stopped behind the chair in which the Major was sitting, held a pistol directly against the neck of his victim, and fired. The Major fell to the floor. Roberts left the room again, and came back to see the Major beginning to move. He walked up and again fired at his right temple. The outrush of blood from this wound relieved the Major a little, and, as he said,

"I knew if I could get on my feet I could make a fight for it."

He opened his eyes and saw the tongs. With these in his hands, he jumped up and attacked his intending murderer. The tongs were smashed against Roberts' skull, after which the Major found a large black wine-bottle and smashed that in the same manner. Two or three times, Roberts seemed to be down and out, but he would recover his feet, and—a hideous sight—come lurching toward the Major, who was trying to find an escape from the apartment. At last, Roberts fell on his face as though dead; the Major pushed him through into the front room, shut the folding doors, and leaped out the window.

Major Murray's story was corroborated by all the facts known to the jury, who brought in a verdict of "justifiable homicide"—this amidst the applause of the crowd of spectators.

Roberts' motive for the attempt at murder seems absurdly inadequate, but it is probable that, in his desperate infatuation for Miss Moody, he thought that with the Major out of the way, he might somehow become the heir to her affections. How he planned to dispose of the body is not clear: perhaps, in the mass of other rubbish which filled his strange dwelling, he thought that the corpse of a retired officer would pass unnoticed.

If you should be eccentric enough to look at The Times for April 1, 1907 you will find this, under Deaths:

MURRAY. On the 28th March, at Ossemsley Manor, Christ-church, Hants, Major William Murray, late 97th Regiment, and 10th Hussars. Service Newmilt'on, 9 a.m., Wednesday. Cremation, Woking. No flowers, by his special request.

All the bullets of that damned fellow, upstairs, had not prevented the gallant Major from reaching the hearty old age of 88. But not even in the Crimea—if he was in that war, which is doufitful—did he ever come so near death as on that day when he fought "like a demon" against a man whose name, and whose purpose, were alike, to him, a mystery.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now