Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowNow we are six

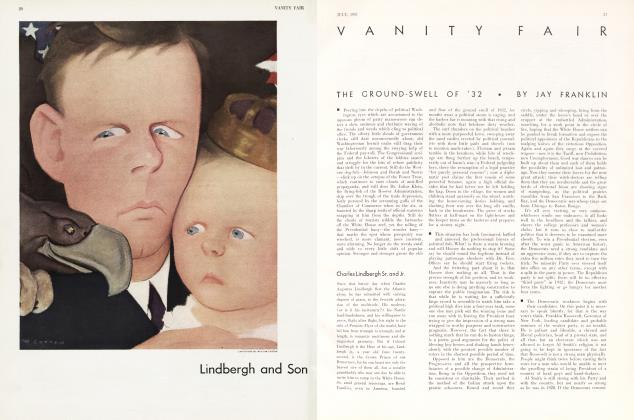

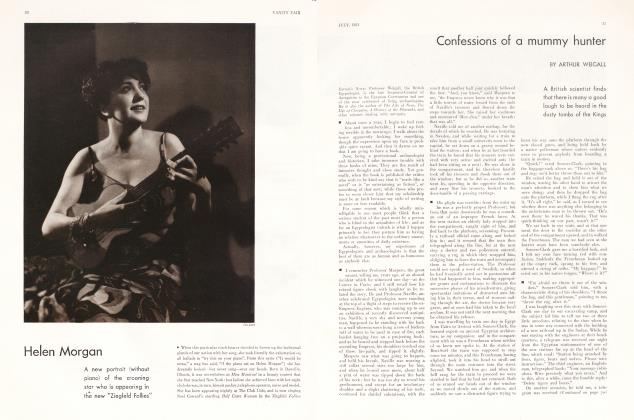

GEORGE GERHARD

Pen portraits of a sextet of dictators who by word and by sword have guided Europe's destiny

■ Personality and power! Is this the twentieth century panacea for the ills of an ailing world? If so, the six strong men of the Eastern Hemisphere share these qualities in abundance. Although they are totally dissimilar in everything else, Stalin of Russia, Mussolini of Italy, Pilsudski of Poland, Briand of France, Hitler of Germany and Gandhi of India, all are dictators of importance, makers of history.

One was almost a priest and is now more than a czar; another, a blacksmith's son, outCaesars Caesar; the third, a swashbuckling musketeer, cusses his way into the leadership of a nation; the fourth is a Paris boulevardier cast in the role of Prince of Peace; the fifth, a crazy fanatic, spars for the title of Germany's first "strong man" since Bismarck; and the last, a ninety-pound bundle of skin and bones, defies the imperialism of Britain and dominates a nation of 320,000,000 souls.

Their methods are different, but their goals are the same. Charlatan, poseur, saint, tyrant, sabre-rattler—each is fighting for what his people needs most, whether it is independence, power, wealth or glory.

Joseph Djugashvilli, alias "Stalin"—the Russian word for steel—was born in the wild Georgian district of the Caucasus, where even to this day vestiges of feudalism are far more common than plumbing in the castles of former Czarist princelings. Young Joseph won a scholarship, and at the age of thirteen began training for the priesthood. Four years of study gave him nothing more than an undying hatred of the Orthodox faith. At seventeen, he bade it farewell in favor of revolution. From theology to ideology was only a step for this hot-tempered, untamed youth and as his monasticism quickly gave way to Marxism, he trod the usual path of revolutionaries to punishment and exile.

Then he met Lenin, the beacon light of his youth, who, dying, said of him: "This man is too hard for me!"

Under Lenin, Stalin was trained in the school of hard-boiled political dogma. He is still following the creed of his master unwaveringly, with the same dog-like devotion he showed in the darkest days when the spark that was to light the flames of a Communist revolt seemed hopelessly weak.

The iron will that even Lenin feared has never deserted Stalin. He fought with it and ruled with it, until today it forms the very backbone of the Soviet regime. Trotsky tried to resist it and found himself in exile. Rykoff also tried and was promptly shown the door. Doubtless many more, equally prominent in Soviet politics, but not sufficiently strong to oppose the master, will follow a similar path.

Stalin is without official position in the Soviet Government. He is chairman of the Central Executive Committee of the Communist Party, called ZIK for short and the benefit of tongue-tied peasants and foreign newspaper correspondents. As such he stands as dictator over a population of 160,000,000. His premiers and Commissars are puppets and rubber stamps. Godhead of a godless state, his is the hand that guides the spread of the Communist doctrine not only in Russia but in every country of the globe.

In such a position, Stalin could not have succeeded without some power denied to most men, for he is lacking in most of the attributes of a great leader. He is utterly singleminded, unintellectual, deficient in mental agility, creative ability and oratorical brilliance. His ignorance of mass psychology is as pitiable as is his envy of more gifted men.

But Stalin is "steel" from the buttons of his rough jacket to the innermost depths of his souL And he has a certain naive keenness which has enabled him to organize and make something dexterous, plastic and patient out of his fiery Georgian temperament. He ends unrest among his people by softening the rigorous measures of the Five Year Plan, only to enforce them with added vigor a few months later. He causes brilliant men to be sentenced to death for intellectual conspiracies, and then wins their undying support by setting them scot free.

Somehow, though crude and unpolished, Stalin has made himself a diplomat of rare skill.

■ Very different is that twentieth century Roman, Mussolini. Brilliant, courageous, despotic, he offers with one hand a peaceful millenium founded on the glorious traditions of his race, and with the other he threatens the world. His sonorous declamation is a challenge to his own people to revive the splendor of Rome, to re-enact the conquest of Carthage, to restore the Forum as the capital of the world's greatness.

"All this is buried," he shouts, "beneath the ashes of an ungrateful Italy, of cowardice, forgetfulness and unchivalrous behaviour. Shake off your weakness! Reap the laurels that are yours! Conquer yourselves and conquer the world—follow me!"

"Let the world shudder and hate," says he. "Fifty years will see Fascism universal."

Son of a blacksmith, Mussolini also knows the touch of steel. His is the blue metal of a Toledo blade, hard as a diamond, yet sufficiently flexible not to break. It was this blade he unsheathed when, after a youth spent in revolutionary activity, in smoke-filled cafes and at the helm of an oppositionist newspaper, he heard Italy crying for a strong man to combat the growing tide of Bolshevism. It was not that Italy needed Fascism. It simply needed a man of Mussolini's stamp, and he had the foresight to choose the inspiring symbol of ancient Rome for his banner of victory.

A disciple of Mars, Mussolini found only one available public enemy in 1919; that enemy was Communism. Against the Reds who were tyrannizing and terrorizing the whole country, Mussolini launched his "Roman Legions," his fearless Blackshirts. In a month it was Mussolini here and Mussolini there; and before long, Mussolini was, and still is, everywhere.

His superior quality as an organizer, an orator and a statesman soon pushed him to the fore, and his popularity with his own people has grown in direct proportion to the antagonism of foreign countries. At the top he remains, while his enemies are ground down ruthlessly beneath his heel, and at the top he expects to stay until his call comes to appear without further delay in Heaven or Hell. When he goes, Fascism as he inspired it goes too. For his is not the triumph of an ideal or of a policy. His is the personal greatness of a soldier and a hero, and how deep a mark it will leave on history, time alone can tell.

■ Into the uncompromising harshness of international affairs, Aristide Briand has injected the mellowness, the blandness of Paris, the easy-going atmosphere of the cafes of the Grands Boulevards and Montparnasse, where he spent his youth.

To Geneva, Briand brings a diplomacy as gentle as a summer breeze blowing across the Seine, as resonant as the chimes of Notre Dame, as sweet as the dainties of the Boulevard restaurants, and with it he shapes the destinies of nations. To Briand a recalcitrant statesman is a somewhat untractable midinette to be coaxed, cajoled and finally swept to surrender by statesmanship as delicate and as smooth as the crepes Suzettes which he serves at his magnificent dinners.

Briand has accomplished more by these repasts than by all the debates across the green baize tables of the Geneva and Locarno council rooms. He finds out what his enemies like to eat, serves it to them abundantly, and when their stomachs are full, "between a pear and a piece of cheese," preaches his doctrine of a United Europe.

Briand's technique is not that of a sabrerattler. He is a seducer, a hypnotist, a master of words and emotions. There is no other man in Europe who, by bringing out of a silk hat the dove of peace, could bring the clanking militarists to their knees. He saturates them with wine, gorges them with dainties and, with the coyness of a youth in love and the power of a master orator, dissembles their jealousies and hatreds and takes them to his arms. He is not so much the spirit of France as he is the spirit of Paris. Even in international politics, the City of Light is irresistible.

(Continued on page 76)

(Continued from page 49)

A disciple of the gods of violence, Marshal Josef Pilsudski has made Poland the "Sarajevo" of modern Europe. Fiery in temperament and ferocious, he wraps his cavalry man's legs around the powder keg of Europe and defies the world to push him off.

Pilsudski's career started at the turn of the century when he was exiled to Siberia for his ceaseless activities against the Russian regime. Somehow he escaped from his prison camp and made his way to Cracow, where he worked secretly until the war allowed him to clank into the open.

Then he organized his famed Polish Legion against Russia, whose people he hated (and still does) more than anything else on earth. He directed them against the double eagle with a hate born of centuries of oppression, during which the Poles suffered merciless political and military persecution at Russian hands. Pilsudski united his Legion with the German army during Ludendorff's campaign against Russia, in return for which Germany promised to establish Poland as an independent nation.

This promise was not kept, and Pilsudski was made a prisoner of war by the Germans he had aided. Immediately upon gaining his freedom, he directed his Legions in turn against Germany, which he had come to despise only a little less than Russia.

Pilsudski's coup d'etat may one day be described by posterity as a great contribution to Poland's progress. But it is safe to say his thirst for power was less inspired by Poland's future than by Pilsudski's love of show.

Pilsudski's greatest sorrow is to part from his bold Legionnaires even for a moment. He wanted to take them into Parliament with him; it took all the persuasion of his friends and protests of his foes to convince him that Poland would be better off if he could forego doing so. But before the Marshal gave in, he treated himself to one of his magnificent verbal eruptions in Parliament, one of those blasphemous speeches that always make front-page copy (in judiciously censored form) throughout the world and which form the basis of his enemies' unceasing attempts to have him incarcerated in an insane asylum.

Militarism has become a mania with at least four of the dictators. Stalin dotes on his lancers and machine-gunners; Mussolini is mad about his Caesarian corps; Pilsudski is enamoured of his Polish Legions and Hitler is soothed by the lullaby of guns.

The German Fascist .leader is nothing if not ingenious. His four years in the trenches gave him a training which enabled him to mobilize a formidable Fascist army. But at present he is showing an even more extraordinary ability to utilize a hitherto unknown weapon in his conscientiously continued political riots—white mice!

Genius, according to standard rules, is proved by versatility. Mussolini carried out a successful campaign against the anti-Fascists by the simple and paternal expedient of cramming these recalcitrant children full of castor oil. Hitler is increasing his personal popularity by releasing swarms of scampering white mice in crowded meeting halls and theatres. Certainly both thus qualify as heroes of unusual calibre, vision and profundity of thought.

But there is more to the Hitler question than the commandeering of rodents to aid German Fascism. It is one thing to tell the people that they deserve prosperity and a more capable government, and quite another to give them these things, as Mussolini did. It would appear to be incomparably more difficult to tell the people how poor and mistreated they are, to promise them wealth, liberty and a bigger, better and brighter life, and then do nothing at all. Personality must indeed be strong when oratory engenders no call for action.

This is the peculiar mastery of Hitler. The other dictators surely must look with mixed feelings and some envy upon this outstanding statesman who is able to seize power, prestige, glory and greatness of a sort without embarking upon any actual aim or constructive scheme.

But among these latter-day "immortals," most of whom fight fire with fire, or intrigue with intrigue, there is one whose battle cry is prayer, whose weapon is passivity. He is Gandhi, who beards the British lion with a spinning wheel.

Despite his gentleness, his patience and idealism, none of these six strong men has been more unwavering than Gandhi. Since his early days when the dream of an independent India was a chimera, Gandhi has been preaching, guiding, leading, gathering about his banner hundreds of thousands willing to undergo physical torture for the sake of an ideal.

Gandhi's success (and it is due mainly to his pioneering that India at long last is on the road to freedom) is in itself a repudiation of the militarism of four of his "colleagues" and the circuitous diplomacy of the fifth. His activities have been those of a prophet and redeemer; he has instilled in his followers his doctrine of peace, patience and love of fellow-men.

Now, with the problem of India's independence seemingly on the road to solution, Gandhi is at his zenith. Known as the "Mahatma" or Holy Man, the spiritual leader of millions, his simplicities and quaint customs have become legends. His day of silence, his prayers and fasting, his loin cloth and homespun garb, his diet of goat's milk and figs, coupled with his genuine love of humanity—rare in this materialistic age—and his brilliant leadership have made him a unique figure in the world today.

Thus it is in dictatorships we see an incongruity of leadership and a uniformity of goal. Many roads, they say, lead to Rome. So long as some great achievement is inscribed in the book of history, so long as the hand of progress is moved forward a bit on the dial of the ages, it is best to cheer the result and not censure the method. Napoleon, you remember, founded an Empire on a charge of grape-shot.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now