Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

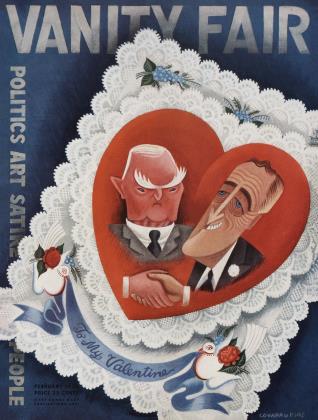

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe gliding chancellor

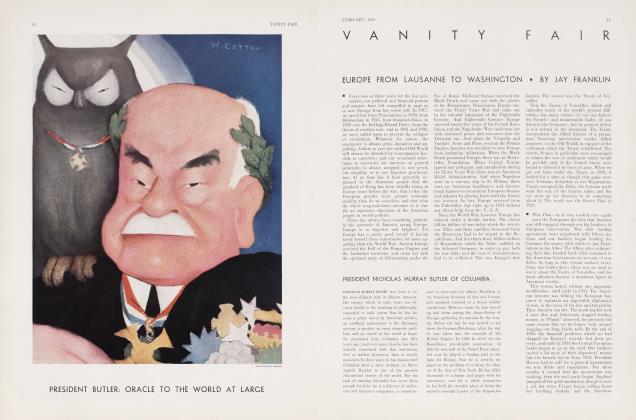

GEORGE GERHARD

A portrait of von Schleicher, the man who has control over more power than any German leader has had since Bismarck

He has been described as a diabolical master-mind, a prince of intrigue, a creature of duplicity, a Richelieu who wears the metallic uniform of a German general in place of the cowl and beretta of a Cardinal. Emerging into the full blaze of political limelight suddenly after the disappearance of the clerical Brüning, he became the "mystery man", the dark "power" behind the Hindenburg throne. The world thought it heard once more the rattling of the Prussian sabre; it let the name of Schleicher be merged with the memory of Bismarck; it fancied the return of the "mailed fist" and of all the other stage-props so indispensable to pre-war Germany.

Behind an ordered desk in a tall room in one of those quiet buildings in the Wilhelmstrasse, Berlin, sits a slender, well-built man, slightly stoop-shouldered, with trim moustache and close-cropped hair. Clearly, he is a military figure. But then again he is not. The man's eyes twinkle, he smiles, his conversation is graceful, lie clinches a point with a smoking-car story, he is suave, he is patient. Responsibilities seem to weigh only lightly upon him. And when evening comes, lie will exchange his diplomatic cutaway for evening dress, to become one of the most desired and brilliant diners-out in social Berlin. The man behind the desk is the Chancellor. He is Lieutenant-General Kurt von Schleicher, also Minister of Defense, and also practical Dictator to the German people.

It was just about a year ago that the name of Kurt von Schleicher began to appear prominently in the cables from Berlin. Before that he had been merely one of many military figures still powerful from war-days; he was famous in Germany chiefly because he was the youngest general in the army and did an unusual thing by remaining a bachelor until the age of forty-nine and then marrying the divorced wife of his own cousin.

But when it was seen that he had gained the confidence of President von Hindenburg and was apparently pulling the strings which made the Reich run (although it ran with creaks and groans), the correspondents elevated him into a major mystery. Speculation over his aims and goals began and has never ended. Suspicious France greeted the first serious mention of his name with querulous wonderment. Who is this von Schleicher, exclaimed the Journal des Débats in Paris, ' dont le nom seul est un programme. Schleichen—se glisser, s'esquiver doucement, louvoyer?" (Trans.: to slide, to escape, to tack.

Chancellor von Schleicher can hardly be said to have patterned his career after the definition so strangely contained in his fine old family name, which, while it sounds soft enough in French, can be translated into our own hard Anglo-Saxon only by the ugly word "sneaker." And yet it cannot be denied that von Schleicher has moved stealthily, as his name implies, gumshoeing his way through the army ranks, sliding into the confidence of the aged president in the palace in the Wilhelmstrasse, silently making and unmaking governments, hobnobbing with the Hohenzollerns but remaining close-mouthed concerning his actual plans about them, siding with Adolf Hitler in a crisis and then grinning to himself as the Nazis began to break apart when their leader began to call himself Mussolini. With his ease and his intrigue, his silence and his urbanity, he is in every sense "the gliding Chancellor."

The explanation is that this brilliant army officer, with one foot in a military boot and the other in a dancing pump, is probably the most patient man in the world today—with the possible exception of the immovable Mahatma Gandhi. For thirteen years he waited before injecting himself into the political life of the nation, and he had the pleasure of seeing the Social Democracy that all old-guard monarchists detest die an agonizing death in the muck of its own failures. He is still waiting, if not for an actual restoration of the Hohenzollerns, then at least for Germany to cut loose from the demoralizing influence of rampant political partisanship and roughneck parliamentarism, and to start back on the road to discipline.

Only infrequently von Schleicher comes forward and shows his hand. He showed it when he dismissed his own appointee to the Ministry of Defense, General Wilhelm Groener, because that official was too short-sighted to see danger in his decree abolishing Hitler's 500,000 storm-troops. It was better for Groener to be politically dead than Hitler to be antagonized into impulsive action. Another showing was von Schleicher's vigorous speech over the radio insisting that Germany was through playing with sparklers and cap pistols while the rest of Europe amused herself with heavy guns and 5,000-ton submarines.

Still another showing was when the Reichstag's 51 Nationalists (remnants of the "Junker" class which von Schleicher represents) introduced a proposed constitutional amendment which would have empowered von Hindenburg, on his deathbed or on the threshold of retirement, to designate his own successor. Barring an immediate monarchical restoration with Crown Prince William chosen as regent, von Schleicher would naturally have fallen heir to the job. The Reichstag spiked this seemingly obvious attempt to create a Hindenburg-Schleicher-Hohenzollern dynasty, but the scheming that lay behind its introduction was an example of Schleicher's daring.

The sharply pointed spike that once topped the helmets of German army officers is known as the "Pickelhaube." Beneath it sits von Schleicher, living symbol of a tradition that still flourishes, in his native Brandenburg and Prussia at least, despite revolution, Social Democracy and Hitlerism. With the help of other aristocrats whom he has picked as cabinet officers to override the Reichstag, von Schleicher is keeping the "Pickelhaube" sharply pointed and glistening. At present, it is being used chiefly as a symbol to make politicians hew to the line, and to present to the world something like a united front in the German fight for equality and liberation.

Whether von Schleicher plans to use the "Pickelhaube" as a means to stir up a monarchical revival is still an open question. If conditions become propitious within his own time, he doubtless will do so. For von Schleicher has never made a secret of the fact that he would like to see dignity and power once again restored to the family of which Crown Prince William, one of his closest friends and dining and dancing companions, is the leading member.

In all the hue and cry about von Schleicher's mysterious aims, it has been overlooked that his strange entry into the political arena brought about almost overnight a triumph of statesmanship. It achieved what the wails of the Socialists for thirteen years and the threats of the Nazis for three years had failed to do. It rid Germany of the burden of reparations.

Von Schleicher alone was responsible for persuading von Hindenburg to appoint Lieutenant-Colonel Franz von Papen as Chancellor of Germany early this summer. In the space of a few weeks von Papen had so clearly and wholeheartedly stated the German case at Lausanne that France—surprised ever since and regretful of her own generosity—agreed to wipe out all but ten per cent, of what Germany has never called anything but "war tribute."

Von Schleicher had rare vision in choosing von Papen, and just as good sense in removing him when he saw that political opposition to his choice was endangering continuance of government without parliamentary sanction—the keystone of his power. And yet at the time of his appointment, Germany accepted von Papen merely because he appeared to be the personal choice of von Hindenburg. France tolerated him chiefly because he was married to the niece of a French marquise and could speak French nearly as fluently as German. America could think of nothing but his Sancho Panza foolishness and jingoistic excesses while military attache at the German Embassy in Washington during the war. Britain was equally annoyed and publicly wondered whether the United States would take umbrage at the appointment as Chancellor of a man who had been shipped off from America, stigmatized as a spy and a meddler.

Continued on page 62

Continued from page 16

In his half-century of life, von Schleicher has played a waiting game. He played it during the war as an obedient member of the truckling general staff which Bismarckian tradition demanded. He played it afterward, when as chief of the Free Corps which later became the Reichswehr, he turned a deaf ear to the respective picas of Kapp and Ludendorff and Hitler to join in violent movements to overthrow the hated bureaucrats and money-wasting Socialists who held power in Berlin. He waited in a different sense just at the close of the World War when he stood steadfast beneath his proud "Pickelhaube" against von Hindenburg and Ludendorff and refused to hand the German army over to the Bolshevists who were overrunning Berlin. He put down that Red Revolt after uttering a crashing "No" to the demands for surrender, and then sat back to wait again, in calm silence, until Germany's fling at democracy should be hoist by its own petard.

Future historians will have little to write concerning von Schleicher's early life. It was a regular page from the Junkers handbook. The "von" in his father's name obliged him to choose the government or the army and he picked the latter, entered military school at the age of twelve and six years later joined the famous Third Regiment of Footguards as a lieutenant. It was this regiment that von Hindenburg once commanded and in which the President's son also served.

Now the two officers are together again in the Wilhelmstrasse, with the positions somewhat reversed. Dictatorial authority (as provided for in the German constitution when political parties become so irreconcilable as to fail of any majority in the Reichstag) becomes guesswork in the hands of an 85-year-old man long out of touch with the world. Von Hindenburg is rightly revered as a staunch oak, but he would be the last to deny that he is under the influence of ambitious advisers. It was Ludendorff who persuaded von Hindenburg to dismiss von Bethmann-IIollweg many years ago. It was von Tirpitz who induced the reluctant Field Marshal, ready for quiet and peace after a life of duty, to accept the presidency. Today it is von Schleicher who does all the advising.

Faithful to whatever task he is given, loyal, smiling, never tiring, blessed with an uncanny ability as arbitrator, full of charm and with a great fund of smoking car stories, a born psychologist, able to obtain pledges of non-violence from the volatile Hitler, capable of lunching with the Crown Prince one day and of drawing up a program satisfactory to the Communists the next, von Schleicher is the real Godsend to a troubled Republic. Perhaps he may also ring the death-knell of that Republic, and be the first to kneel again before the crown.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now