Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE EDITOR'S UNEASY CHAIR

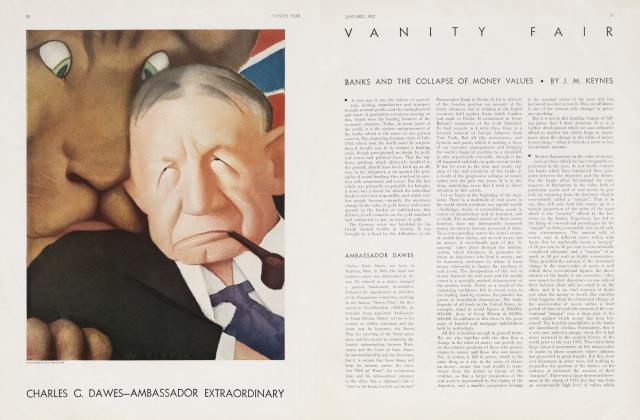

Great economist

John Maynard Keynes, whose article, Banks, and the Collapse of Money Values opens this issue, is one of the foremost, if not the foremost, economists in the world. Born in Cambridge, England, in 1883, he was educated at Eton and King's College. He served in the Treasury throughout the years of the War, and was its principal representative at the Paris Peace Conference, as well as Deputy for the Chancellor of the Exchequer on the Supreme Economic Council, which sat from January to June of 1919. He has written numerous long treatises on monetary reform, and on treaty revisions.

Tired crusader

Dear Sir:—In Vanity Fair of November, Mr. Clarence Darrow, advertising his despair of the repeal of the Eighteenth Amendment, writes the obituary of the career of one of the most picturesque battlers for unpopular causes that his generation has known. The voice that was raised in Tennessee in defence of the Darwinian theory, that thundered its championship of Debs, socialist and pacifist, during the war—that voice has piped down and now says of repeal of the Eighteenth Amendment that it involves too much hard work, and that it is therefore better for us to accept as our ultimate goal some easy way of getting a drink! "Let us repeal the Volstead Act," he begs, and make faces at the Eighteenth Amendment, which was "not written to be repealed but to make a change impossible."

Mr. Darrow goes on to say that we now want "the drink for the drink's sake." But drink for drink's sake is already with us, copiously, intoxicatingly, and as the Wickersham Report tells us, ever more and more inexpensively and with greater safety.

We already have nullification of the Eighteenth Amendment, and all the shameful evils of nullification. But if the drink for the drink's sake is the aim, why in the name of consistency do we need to make any change in the present status?

But, of course, that is not the aim of enrolled Anti-Prohibitionists. The restoration to the Constitution of its true function, the restoration to the States of their inherent rights, the breaking of the sinister alliance between bigots and fanatics on one hand and the liquor racketeers and gunmen on the other, the substitution of temperance for unbridled intemperance—these are the aims of the enrolled Anti-Prohibitionists. And these demand the repeal of the Eighteenth Amendment. Nothing less will suffice. Anything less is a mere gesture of temporizing, of expediency.

To repeal the Volstead Act, which Mr. Darrow roseately envisions as the easy accomplishment of "one wet administration," would be, while a blithe derision of the Constitution, merely an invitation to the "drys" to continue their activities for a repassage of the Volstead Act by tbe next Congress. The merry game of "now you see it, now you don't" would be on indefinitely—or until the Eighteenth Amendment is repealed.

No one knows better than Mr. Darrow that an amendment to the Constitution can be repealed. He outlines the procedure in his article.

We all concede that it may be a long, laborious job to repeal the Eighteenth Amendment, although we are astounded by the amazing spread of the sentiment for repeal. It is the only way of fundamental redemption.

Does Mr. Darrow so despise his fellow citizenry as to maintain that it can be duped forever, that it will forever be willing to submit to any degradation of crime, corruption and disorder, rather than to admit that it has made a disastrous mistake?

The Women's Organization for National Prohibition Reform do not think so badly of the American people. We do not shrink from a long task. We are not, Mr. Darrow, interested in having a larger variety of liquor from which to choose. With us it is not a question of drink, but one of Government.

And we venture that you believe with us. We prefer to see you as a temporarily tired crusader, sputtering a bit of nonsense, rather than as one retreating permanently into the Twilight of the Gods.

PAULINE SABIN

New York City. (Mrs. Charles S.)

Humorist's daughter

Elizabeth Cobb Brody, in collaboration with Margaret Case Morgan— formerly associate editor of Vanity Fair, who resigned from the staff to take up more creative literary work —wrote the murders which appear on page 34. Mrs. Brody is the daughter of the well-known American humorist, Irvin S. Cobb, and she inherits a generous part of her father's wit and literary gifts. She is the author of two books, Minstrels in Satin and Falling Seed, and has contributed to the Saturday Evening Post, Scribner's and Vanity Fair.

Twenty of the murder-plays to be also entitled Murder in the Home will appear shortly in book form under the imprint of Ray Long and Richard R. Smith, Inc.

Furor we care

Dear Sir:—In the November issue of your magazine, as you might conceivably wish to forget, is recorded a diaristic discourse perpetrated by Douglas Fairbanks, Jr.

I could occupy many pages in the delivery of panegyrics to his most illuminating style but I will deprive myself of that pleasure and recount only the phrases displaying marked felicity and exceptional grace.

Born of humble parents Debonair and dashing Steadily grew in popularity Vicious and vitriolic Made of Finer Stuff And since lie speaks authoritatively of adjectives I am sure you will excuse the mention of his use of the word morbid.

In all one receives a most delicious sensation, namely an inclination to violent homicide, and since one may not gratify one's every desire, this is sent as an alternate expression . . . .

I approve generally of your pretty periodical and the efforts of your contributors, particularly George Jean Nathan, but I object to the printing of the "redolet lucerna" drivelings conceived by moronic actors in cataleptic attacks of "furor scribendi." That, I consider, is vulgar, and inconsistent with your usual editorial tone. . . .

RALPH ALAN MACKAY Spokane, Washington.

P.S. "Mundus vult decipi" as Mr. Cabell has no doubt shrewdly observed, is the eternal verity in point for M. Fairbanks. Tell him to cleave to the fire of his noble father, since we of the populace would fain continue to cherish our illusions.

A collected volume of Douglas Fairbanks, Jr.'s work is shortly destined to appear, by popular demand, under the imprint of John Day.

Wherry good

Henri Matisse, as a man, is precisely what the world has thought him not to be. For twenty years he has withstood the epithets of madman, impostor, decadent, showman. Actually, and at the risk of disappointing our readers very greatly, we must confess that he is a most normal, amiable, industrious and modest man. His family comes first, even before his art; next in order, his painting and sculpture, to which he gives eight hours of his day; third in order, his outdoor exercise—in his case, rowing in a wherry. Of all the honours that have come showering upon him during the past few years, none delighted him more than the medal which proclaimed him officially the most industrious of oarsmen on the Riviera. The recent Matisse exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, in New York City, marked a record attendance for the "one man" shows of the year, in the metropolis. His painting, Lady with Plumes, appears on page 41.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now