Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowPOLITICAL STOCK-YARDS REPORT

JAY FRANKLIN

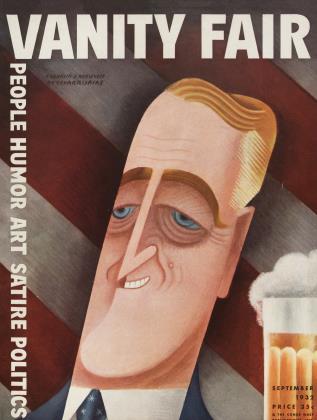

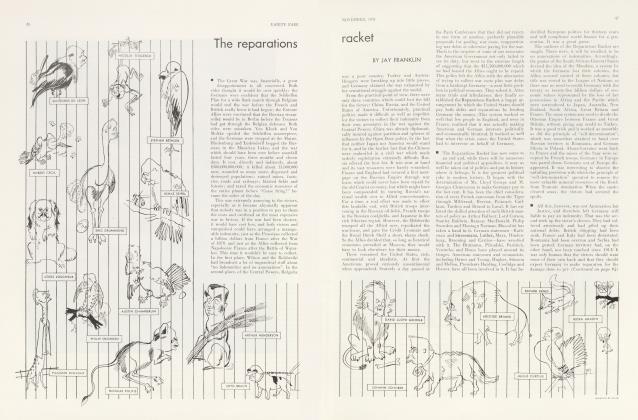

Last June in Chicago, two great droves of snorting, bellowing, bleating, squealing

politicians, wild-eyed and odorous, were sent down the run-way in the Coliseum and, amid the whirring of well-oiled machine politics operated by remote control, were converted into so many packages of boloney and sides of beef. The Republican and Democratic National Conventions came, saw, and were conquered by Messrs. Hoover and Roosevelt, the Swift and Cudahy of the political packers. It was a smooth performance, and despite the anguished antics of the inmates of the partisan abattoirs, the result was what all disinterested observers had predicted in advance: the marketing of two candidates wrapped in cellophane, untouched by human hands, frozen by the "bird's-eye" process into packages of potential votes, to be consumed next November.

Of course, the recent political conventions are old stuff, so far as news is concerned, but, unfortunately for America, they keep repeating themselves with the dreadful regularity of a recurrent nightmare, and not only represent a prophecy of what we may expect in the future but should be regarded as symptoms of the political paranoia which has been responsible for existent social and economic convulsions.

At Chicago, two foregone conclusions collided with two forlorn hopes, and the result is the least attractive bill of fare which has ever been offered to a distracted nation in the throes of a great crisis. Hoover is all right. He means well and he tries hard. The fact that he is stubborn, thin-skinned, and a poor politician should not blind Americans to his extremely solid qualities as an organizer and an economic statesman. The country doesn't happen to like the qualities which he represents, but that is no more Hoover's fault than is the world depression. Roosevelt is all right. He is quick-witted and a gentleman. The fact that he is an opportunist and a political trickster should not blind us to the fact that he has deliberately identified himself with progressive policies and liberal principles and that we may need a shifty broken-field runner rather than an elephantine line-plunger if we are going to make first down in the next four years. Charlie Curtis is all right. It is true that he is old as the hills, the brother of Dolly Gann and an expert on horse-racing rather than taxation, hut what of it? We shall simply have to pray ardently that President Hoover keeps his health until March 4 if not later. It is true that Jack Garner is a turtle-necked horn-toad of a Texas politician, but what does it matter? At worst he would be better than Curtis and we have the best possible assurance against assassination in the persons of our two Vice-Presidential candidates. Not even a madman would wish either of them to step into the Presidency.

Of the two platforms, the Democratic is the better, principally because it is the shorter. On the other hand, the Democratic Party is so uncertain, divided, and heterogeneous that it stands little chance of putting through even the Ten Commandments. The Democratic plank on liquor is dripping, wringing wet, whereas the Republican plank is such an ingenious straddle that the Borahs claim it is wet, while the Butlers claim it is dry. Instead of pleasing both sides, it pleases neither. On other counts, there is little to choose between the two sides. The Republicans are still dreaming that automatic prosperity will return with two chickens in every bed and two sweethearts in every port. The Democrats have rushed back to John Stuart Mill and the Mid-Victorian era for their economic principles, and back to Thomas Jefferson—God bless him!—for their political ideas. The Democrats vigorously oppose remission of the War Debts, knowing all the time that the debts will be settled by the economic rather than the political necessities of the time. The Republicans have a lot of kind things to say about the tariff, and are giving vent to a lot of vague propaganda that Herbert Hoover is a miraculous blend, aged in the wood, of the best features of Abraham Lincoln, George Washington, and Buddha. The Democrats, after spending several months in proving that Franklin Roosevelt combined the least desirable qualities of Benedict Arnold, William Jennings Bryan, and Mahatma Gandhi, suddenly decided that he's not so had after all, that he is in fact a darn good candidate, nay, the greatest man ever nominated by the Democratic Party in all its history.

The Republican battue was marked by the machine-like precision with which four hundred Republican postmasters, stiffened by the kitchen-tested Southern delegates from the rotten boroughs below the line where it is illegal to forget the Civil War, voted at the direction of the White House. The Republican Party—that part of it which was not in the chain-gang—was dripping wet, but Hoover pressed the button, and they all obeyed orders. Even Ogden Mills forgot that he had been present at the New York caucus which had voted for repeal, and when he was reminded of the fact became so furious that he lost both his temper and his dinner. He obeyed orders, like a good soldier, and denied that he knew anything about Prohibition repeal. Many of the Hoover Cabinet abandoned their posts and the public's business in Washington during a critical period in national and world affairs to go out and lobby for the Great Engineer. Secretary Stimson was there, as were Wilbur and Pat Hurley, to foil the efforts of Senator Hiram Bingham and the eternally candid Nicholas Murray Butler to put a wet plank in the platform. One of the more interesting fossils of the pre-Taft era was excavated by some ingenious political searcher for dinosaur's eggs, and produced a Republican liquor plank as long as the entire Democratic platform, which said nothing at such vast length that nobody to this day knows whether Jim Garfield was quoting from the Died Scott decision or had brought the wrong notes. There was the usual false alarm that Borah was going to start a third party and Senator Fess went around making the usual clucking noises. Senator L. J. Dickinson of Iowa delivered a keynote speech which would have made anyone with the slightest Presidential self-respect blush and hang his head. Herbert Hoover was praised in terms which, if slightly more restrained, would have done credit to the Almighty on the seventh day of creation. Hoover was even praised for doubling the population of the federal prisons. And yet the extraordinary thing about it was that everyone who knows how things are done is fully aware that the speech must have been read and approved in advance by the President himself.

Then came the nomination. There were two candidacies. One was the open and determined candidacy of Herbert Hoover to succeed himself—the foregone conclusion of the convention. The other was the clandestine and boot-leg candidacy of Calvin Coolidge, the forlorn hope of the conservative wing of the party. Its real leader was Senator France of Maryland, running as an independent candidate. However, when France mounted the platform to nominate Coolidge, he was promptly ruled out of order. He started to speak and had just got as far as "Cal—" when a couple of Republican bouncers clapped their hands over his mouth, dragged him out and put him under arrest, lest the magic name of "Coolidge" start an ovation and a stampede which would make Herbert Hoover look extremely silly. It was all over quickly and with little bloodshed. Then the administration, just to make sure that there would be no hanky-panky about nominating an able man for the Vice-Presidency in order to make it possible for the President to resign in his favor, insisted on Curtis as Hoover's running-mate and the Republican show was over.

The Democratic show was much louder and funnier. For months it had been so obvious that Franklin Roosevelt would get the nomination, barring some staggering political upset, that only the Wall Street bankers and the political "experts" had failed to realize it. The stop-Roosevelt movement had gathered around the Smith-Raskob-Shouse group, and it took the form of sniping propaganda, "favorite son" and "dark horse" tactics, and a little partisan manipulation of the Party machinery to hurt Roosevelt. Roosevelt, however, went right ahead gathering up the delegates of Alaska, the Canal Zone, the Virgin Islands, the Western and the Southern states. Frozen out of Illinois, Ohio, and New York City— the key points in the Presidential campaign— with Texas and California side-tracked to Jack Garner, and with A1 Smith ruling .Southern New England, New York, and New Jersey Roosevelt entered the convention a hare hundred short of the two-thirds majority.

The fight then shifted to other lines. Roosevelt boldly attacked the two-thirds rule, threatened to use his majority to force through his candidacy and brought the opposition out in the open. It was found to include A1 Smith, Newton D. Baker, Governor Ritchie of Maryland, Governor Murray of Oklahoma, Governor Byrd of Virginia, Jim Reed of Missouri, John W. Davis, and Jimmy Cox of Ohio. In other words, the Roosevelt opposition included the men who had led the party to dignified hut complete defeat in 1920, 1924, and 1928. That was enough. Roosevelt dropped the fight and went after the permanent chairmanship. Jouett Shouse, who had been consistently anti-Roosevelt in his role of executive secretary of the Democratic National Committee, was bilked of the job, which went to a Roosevelt man—Senator Walsh of Montana. Senator Barkley of Kentucky, another Roosevelt man, was the keynoter and did a manful job in denouncing the iniquities of the Republican tariff after he— Barkley—had just voted for some of the rottenest tariff grabs in our political history. Roosevelt men dominated the committees on credentials and resolutions. The Roosevelt delegates were seated and resolute skirmishing went on between Farley and Huey Long, on the Roosevelt side, and against Senator Walsh of Massachusetts, McAdoo, and such "favorite sons" as Melvin Traylor, of Illinois, Governor White and Senator Bulkley of Ohio, and such background workers as Carter Glass, Bernard M. Baruch, Admiral Cary Grayson, and Mrs. Woodrow Wilson. The fight now shifted into the liquor plank. The anti-Roosevelt forces decided that Roosevelt, with the support of the dry South and West, would try to do a Herbert Hoover on Prohibition. Dave Walsh—Smith leader—introduced a dripping wet plank, which he expected to bring before the convention as a minority report, smashing the Roosevelt movement.

This was A1 Smith's Waterloo. Primed for a devastating anti-Roosevelt speech, he found the Roosevelt men supporting the Smith liquor plank, which went over by a vote of four to one. Then the balloting started. In three ballots of an all-night session, Roosevelt's strength crept up but was still about ninety votes short of the two-thirds majority. The stop-Roosevelt coalition had a weak link— William Gibbs McAdoo of California, whom Smith had kept from a nomination in 1924, by deadlocking the convention. McAdoo represented Hearst and controlled the votes pledged to Garner from Texas and California. Everything was planned out so neatly. On the fifth ballot, the anti-Roosevelt men were going to "unmask" some of the "latent" sentiment for Newton D. Baker. There never was a fifth ballot. Hearst did not like the idea of Baker in the White House and said so firmly. McAdoo switched the California and Texas votes to Roosevelt, revenged himself on A1 Smith, and started a band-wagon rush in which all the favorite sons save A1 Smith allowed themselves to be dragged behind the Roosevelt chariot wheels. Smith's lines held fast—Tammany, New Jersey, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts going down with him to defeat—but the rout was otherwise complete. There remained only the formality of seeing Garner paid for his sacrifice of a candidacy which was only created for bargaining purposes, by the nomination for the Vice Presidency. Whether McAdoo will he paid by the Senatorship from California or a Cabinet position is as yet unknown. Roosevelt flew West and delivered a speech of acceptance which contained the happy thought of curing the depression by planting trees, and the Democratic show was over.

As a result, only a few men survive in either party with their reputations unblemished. Of the Republicans, Nicholas Murray Butler came through with great credit. He fought hard and well for his principles only to see the Republicans cast away the support of the million women voters organized for prohibition repeal by a former Republican Committeewoman, Mrs. Charles H. Sabin of New York. Hiram Johnson of California, who six months ago practically decided that the Democratic ticket would be Roosevelt and Garner, survives with the Republican Progressives, alone and unassailable and probably ready to swing California Democratic in 1932 as in 1916. Borah made some unpleasant noises as usual and George W. Norris of Nebraska, as in 1928, announced that he intended to vote for the Democratic candidate.

On the Democratic side few survived the political slaughter-house. Newton D. Baker played sufficiently safe to be assured of a Cabinet position if he wants it. Governor Ritchie of Maryland and Governor Byrd of Virginia showed up as sportsmen and gentlemen in the face of unexpected discomfiture and defeat. The bitter disappointment of the A1 Smith crowd harmed their prestige in national politics, but young Senator Millard Tydings of Maryland emerged on the national scene as a leader of force, humor, and dignity, in his management of the Ritchie candidacy. Huey Long acted like himself, which is nothing new, and the whole SlmuseRaskob outfit folded its wings and resigned in favor of James A. Farley, Roosevelt's manager. And finally Franklin Roosevelt won through to the nomination, without owing anything to the support of Tammany and in the face of the bitter opposition of the Wall Street bankers. After years of bank failures and talk of Tammany corruption, neither of these things will hurt Roosevelt in the 1932 campaign.

That campaign has officially started, although it has been under way for months before the nominations. Hoover has been playing politics, and usually petty politics, for a long time, with his eye on this election. Roosevelt has been "building himself up" in the public eye as a vigorous if rather synthetic liberal. The Democrats have been accusing the Republicans of inefficiency, waste and broken promises; the Republicans have been saying that it would have been worse if the Democrats had been in power. Both sides have been playing politics with human misery and neither side would welcome a return of prosperity if it would help the other party win the election. Both candidates will turn themselves loose on some good hearty tub-thumping and radio-crooning, and the party pan-handlers are already slipping into the bankers' family entrances for the wherewithal to give the boys in the precincts the necessary frog-skins.

And in the meantime the country is going through one of our nastiest and least necessary depressions. Neither party has any real plan for improving conditions or any real expectation of being called on to do anything but sign the public payroll and listen to orations at party gatherings. It is this fact, rather than the admitted mediocrity of both candidates, the generally recognized tenthrateness of both of the Vice-Presidential nominees, and the customary crookedness of the political machinery, which is disheartening. Our previous crises have produced men and movements for thorough-going political reform. The brand of candidates and policies which come to us from the political stockyards at Chicago savor too much of embalmed beef to constitute wholesome fare for a nation which has the right to demand courage and action from its leaders in time of crisis.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now