Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowA detail of the depression

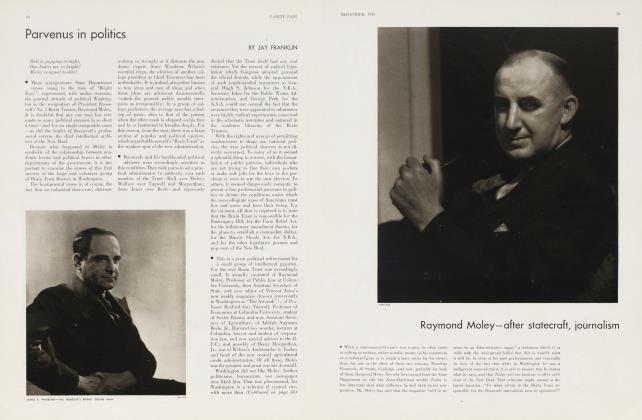

IRVIN S. COBB

A little story containing some interesting pointers on how to deal with the modern blackmail racketeer

If you hadn't known better, you never in this world would have guessed that here and now a blackmailing game was being hatched from its fertile egg. Everything was passing off so nice and quiet and gentlemanly—and ladylike. No harsh threats, no violent protests, no rough language, no nothing of that sort; hut all just as slick as a whistle and as smooth as a snake's belly.

Naturally, when Crofutt—Crofutt was the victim of the plant: J. Warden Crofutt, corporation lawyer and, as the saying goes. Social Registerite—naturally, when Crofutt first was notified by telephone that the publishers of Broadway Brittle desired private conference with him touching on certain unpleasant facts in their exclusive possession, he, being wise in his generation and a lawyer besides, urged that further negotiations be carried on in his office downtown with Morton, Mayer, Crofutt & Mayer, or even better, at his bachelor apartment uptown.

But this didn't suit the astute head of the small, close concern which proposed to bring out Broadway Brittle. Once bitten, twice shy, and Mr. Angus Surray had made one such grievous mistake five years before when he was Little Augie Slawson, and his sprightly weekly was Tenderloin Tidbits. In those intervening years—three of them dolorously served in Sing Sing on an extortion conviction and the remaining two spent in getting again upon his small eager feet—Mr. Surray, née Slawson, had learned the hitter lesson that never should a gentleman in this line of journalistic endeavor put his cards upon the table while on alien premises, where prejudiced listeners might he concealed hack of screens taking things down in shorthand, or a dictaphone he lurking, like some mechanical asp, beneath a chair cushion or behind an innocent wainscoting. From now on, if there was any eavesdropping going on, Mr. Surray would provide the eaves and drill the droppers. Thenceforth and forevermore, all witnesses to all professional transactions whatsoever would be Mr. Surray's own handpicked witnesses and not somebody else's, and their ears and their tongues would be confirmatory ears and, if needs be, corroborating tongues.

"Now, now, now, Mr. Crofutt," Mr. Surray's voice had said over the wire, in the friendly yet gently chiding tone. "You know, without my telling you, that that sort of thing would be away out of line.

"Rut you're asking me to—"

"No, no, Mr. Crofutt, get this straight. I'm not asking you—I'm telling you. I'm telling you that you should he down here at our new offices on West Fifty-Seven' Street —I've already given you the address—at four o'clock this afternoon to talk this little matter over with me and my confidential staff. It's important—no need my telling you that, though—that you should come alone and come prepared to talk business on a business basis."

Therefore it befell at or about four p.m., of the same day, that Mr. Crofutt came to the offices of Broadway Brittle and business was talked.

Present, and taking more or less minor parts in the proceedings, there were, besides the two principals, only two others: namely, Mr. Surray's managing editor, Mr. Rodman, and Mr. Surray's managing ladyfriend, Miss Sampey, whose official title, from eight to five inclusive, was secretary to Mr. Surray.

Now, Mr. Rodman was a large, semi-solid. gelatinous gentleman with two extra chins in front and a spare on behind, and the look on his unjelled face was the nourished, greasy look of a tomcat which has in its time eaten a thousand canary-birds. Perhaps that was why one suety hand of his kept going up to the mouth and wiping away imaginary yellow fluff. Miss Sampey was tall, personable and inscrutable, with a highly-burnished manner of ultra-sophistication and a fixed Mona Lisa smile, whereas Mr. Surray rather suggested a very slim, very keen little surgeon's scalpel bolstered in a Moxie Marcus masterpiece of lounge-suitings.

At length the deal approached its final aspects where the appetizing detail of cash payments inevitably must come up. Mr. Crofutt had seen the "convincer," which by the cant phrase of the trade-guild to which this trio belonged, meant a first-page makeup, tab-size, replete with its picture layout and its blaring headlines set in stud-horse type, and its three columns of text. He still held the ugly thing in his hands-—this "expose" which, if printed, could not greatly harm him. except inferentially, but which, being printed, would make dogmeat of the reputations of persons very near and very dear to him. There was, for instance, his sister to he thought of, and his sister's husband. Mr. Surray and associates had counted on the thinking which Mr. Crofutt would do when he read the "convincer."

"You get our position, now don t you? said the gnomish Mr. Surray, approaching the delectable climax. "To start off Broadway Brittle with a peach of a yarn like this, to come out in our very first issue with a sensation that'll rock the town—well, you can see for yourself what that'll mean to us in prestige and newsstand sales and future circulation. And look at the heavy expense we've already been put to—getting this exclusive story run down and rounded up and having it illustrated and set up and all."

"Runs into big money," added Mr. Rodman, removing a few more yellow pinfeathers from either corner of his thick, moist lips.

"Important money, I'd call it,' murmured Miss Sampey.

"Rut if I should come across, what guarantee would I have that you'd suppress this dirt and keep it suppressed?" inquired Mr. Crofutt.

"Ain't I giving you our word on it—our solemn word of honor?" stated Mr. Surray, rising to his full height and looking more than ever like a sharp little knife partly drawn from its tailor-made sheath.

"Rut nothing in writing, eh?''

"That, Mr. Crofutt, would hardly be ethical," stated Miss Sampey, "as you yourself surely must realize.

"All right then. Let's get down to cases.

. . . How much?"

With the air of one making a considerable financial sacrifice on the altar of compromise, Mr. Surray named a figure. "And that's a break in your favor," he added. "Still, give and take! Rut no check, mind you—currency!"

Mr. Crofutt shook his head.

"Nothing doing at that price," he said. "I can't do it."

"Let's not haggle, Crofutt," said Mr. Surray, sharply now. He made it plain that haggling was to him a distasteful process. "I've quoted you the bottom price. Take it or leave it. Rut listen, besides what this will do to some other people, you gotta consider what this'll do to you, too—you a prominent man-about-town— '

"Man-about-broke," put in Mr. Crofutt. "I suppose you think I'm the only fellow in New York that didn't get jammed in Wall Street?"

"But the firm you're a partner in, and its big law practice?

"What we're mainly practicing at present is not law but economy," said Mr. Crofutt. "You'll have to believe me when 1 tell you that at this moment, except in one direction, I couldn't put my hands on five hundred bucks. . . . But wait, I've got a proposition of my own. You know the Thirteenth National, of course? Perhaps you've had dealings with it?"

(Continued on page 57)

(Continued from page 28)

Mr. Surray half opened his mouth to say yes but checked himself because he would be dealing with the truth, and to him the truth was so rare, so precious a commodity that instinctively he used it with caution and at long intervals only.

"What if we have?" he asked instead.

"Just this: It so happens I own thirty thousand dollars' worth of stock of the Thirteenth National—own it free and clear in my own name. At par value— and even these times, it's stood tip pretty well—that block of stock amounts to practically eighty per cent of what you're demanding from me. I'm willing to do this: The minute I leave here I'm willing to go right over there and, 'for value received', have that stock transferred to this outfit of yours. I'm not going to hock that stock outside to raise funds—-that might leak out and make talk and damage my credit, such as it is; and I'm not going to try to borrow on it from the bank itself to pay you off. I want to get this whole dirty mess washed up in just one quick operation. If you doubt my good faith, one of you—or all of you—-can go along with me and stand by while the switch is being made."

At that last suggestion, three suspicious heads w'ere shaken in unison. But the grin on Mr. Rodman's face was like a widening crack in a crock of soft tallow.

"Mr. Crofutt," said Mr. Surray warmly, "it's a pleasure to do business with a gentleman. You trust us—we trust you. And we accept your terms. It's a cut—but what the hell! I know those people over—I mean to say you can just have those people over at the Thirteenth National notify us by telephone that the transfer has been made. I'll drop by to tell 'em what to do with the shares."

"Then it's settled," said Mr. Crofutt, and got on his feet. His face had been very red, then it had been very white; now it was regaining its natural ruddiness. "Do you want the stock made over to you personally or to your company?"

"Oh. to the company, This is company business, strictly."

After lie was gone, joy among the affiliates practically was unconfined. By reason of a heartening inner glow, the globular Mr. Rodman seemed to be on the point of altogether liquefying into some sort of thick gluten and running down on his own clothes. And Miss Sampey planted herself on the elfin lap of her patron, thus producing the exotic effect of a very willowy sapling growing out of a very diminutive tub; and she wrapped her congratulatory arms about him and, looking down on it, she entreated the top of his tiny bald head to tell her whether Mommer didn't have the very smartest little Poppa in all this great city?

But in that same place, one fair morning not more than ten days later, a lodge of sorrow was being held. The devastating woe which possessed Mr. Surray made him shrilly vocal, made him prone to recapitulate over and over again the tally of their joint distresses, just as one might irritate a sore spot to keep it from healing. And Miss Sampey was aquiver with a venomed rage, so that her accustomed pose and poise were quite shaken off her smooth shoulders. As for the spheroid Mr. Rodman—well, when a fat man really suffers, he suffers all over. Mr. Rodman was congealed to a veritable gruel of grief. Even his voice now had to it a thin, high-strained, soupy quality—like so much whey endowed with power of speech.

"What a bunch of bums and suckers he makes of us from the start!" proclaimed Mr. Surray repetitiously. "Almost I hate that as much as us being busted this way—honest I do!"

"The dirty shyster!" piped Mr. Rodman.

"The crooked double-crossing has-" began Miss Sampey, but Mr. Surray's bleated utterances overrode what would have been terminal syllable and blanked it:

"In advance, from the inside, he knows that dam' Thirteenth National is on its last legs and that when they shut it up right in our faces, like they did yesterday afternoon, that block of stock which he sawed off on us easy marks, not only ain't worth the paper it's printed on but makes us liable for its original value up to thirty-thou'. From the inside, him being a member of their advisory board, he knows already that every last cent of the bank roll we dug up and saved out to start this new Broadway Brittles racket with is on deposit over at the Thirteenth National. And it's still tied up there, and the government will take it —sixteen grand, round figures—to help make up our liabilities on the stock. So now we're flat, and Brittles is cold. And, so help me, we can't even take a chance on getting even with this low-life by passing that stuff about his brother-in-law on to one of the other scandal-sheets, because, last night, after the bank shuts up, we get notice—and the legal evidence, too— that if we do, it'll be criminal libel and curtains up the river for us, because it wasn't even his brother-in-law that got in that jam out in Denver, but a guy with a name like his. All along, from the minute we flashed the convincer on him, he knew that, too, and never tipped his mitt, just pulled us on like an old boot!"

"The triple-crossing bas----", Miss Sampey tried again, but this time it was Mr. Rodman's wan utterance which checked her:

"A notion! We still could hire Crummy Mix's mob to put Crofutt on the spot and teach him a lesson—beat him to a pulp—knock his teeth out— knock an eye out—cave-in his ribs—"

"And where would we dig up the five hundred to pay for that little job?" demanded Mr. Surray.

In the comparative silence which followed this unanswerable question, Miss Sampey succeeded in finishing her twice-balked remark.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now