Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Theatre

George Jean Nathan

OPENING REMARKS.—There are still amongst us a sufficient number of managers and producers who apparently have not heard the news that a big change has come over our theatre. Where they have been all the time that alterations were going on is not ascertainable, but here—at the beginning of another season—we find them obviously under the belief that Tony Pastor is still packing them in with W. J. Scanlan and Evans and Hoey, that the Sire Brothers' Bijou is nightly showing an S.R.O. sign, and that Sarah Cowell Lemoyne will probably be old enough in a year or two now to be cast for the ingénue in The Countess Glucki. That this is the year 1933 and that the theatre, together with its audiences, its playwrights, its critics, and almost everything connected with it, is—and, if it would keep its doors open, must be—a wholly different establishment from what it was even a relatively short time ago, no one seemingly has apprised them. Thus, in the early weeks of the season, we beheld these zombies confidently putting on various plays that might conceivably have drawn in some customers back in 1895 but that, when New Year 1900 rolled around, wouldn't have managed to draw in enough to pay for the one-sheet in the window of Engel's Chop House.

I shall not go into detail about all of these early productions, for the simple reason that they are not worth the critical exercise and for the even simpler reason that, long before this crosses your eyes, most of them will have been interred in the junkhouse. A few horrible examples will suffice to give you the general picture.

In the first place, imagine an ambitious producer, bis thoughts on golden profits, his proemial cocksure smile bestowed upon the hardened play-reviewers, heaving into the theatre of today with a sub-Alwoods sex farce of the vintage of 1915. Imagine such a producer imagining, at this theatrical day and age, with reviewers and audiences ready to get out the axe for anything that doesn't show certain signs of quality, that a farce which smirked heavily over bedroom indecisions and which was written by a man who, in a profound musico-critical mood, grouped Mendelssohn with Bach and Beethoven, would stand a ghost of a chance. Well, you probably can't imagine it anymore than he could when he saw half the first-night audience make a bee-line for the exits at the end of the second act. For the sake of the records, the title of the misguided gentleman's little bag of manure was Love and Babies; its author's name, Mr. McCormack.

Then consider something called A Party. by the English actor, Ivor Novello. Having been something of a success in London, it is possible that the late Charles Frohman would have imported it during his earlier years at the Empire—provided he was in his cups when the deal was put over. But for a producer to import such stuff today, whether a success in London or not, only goes to prove again, and for the steenth time, that what is wrong with our theatrical business is not the movies, the depression, or anything else hut the miserable business sense of so many producers themselves. This Novello play, though an exceptionally poor one, provides us nevertheless with a pretty fair, if in this instance slightly indirect, view of the physiology of much of the London popular drama these days, and why it is so infrequently transplantable to the American stage. With a few honorable exceptions, the bulk of the plays that one encounters in the London theatre suffer from what may be described as a dramatic green-carnationism. The young men who write them are sometimes clever, sometimes moderate!) witty, and pretty generally literate, but their point of view is usualK pink, and always superficial. Their plays have an unhealthy air. Conceal it though they may assiduously try to. there is nevertheless to them the smell of something just a little bit sickly and foul. A peculiar perversity, like a feminine sneer, permeates them. The quiet, unassertive, hut sure masculine quality is missing and, in its stead, there is either a counterfeit muscularity—cynicism in lace shorts—which hoodwinks no one, or a brazen affirmation of masculinity's lack. Some of these plays are fairly amusing, as a female impersonator is occasionally in a refractory vaudeville way amusing, but none of them is1 cannot think of a more pointed phrase —healthily comfortable. The good Lord knows that American popular drama is nothing for us to get patriotic about; as a matter of fact, it is often inferior in relative quality to the English. But, whatever may justly be credited against it—and that is considerable— no one can deny its ruggedness. It has a vigor, a blood beat and an open directness whatever else it has not. There is, in a manner of speaking, a strength to it, whereas in the English equivalent there is a suspicious pallor, a taint of rottenness. And that taint becomes all the more evident when it is felt across the footlights of a crude hut robust alien stage. matters, the chorus in that case being sung either in French or in what passes on Broadway for English with a French accent.

MORE.— A few minutes after the first curtain went up on Come Easy, by Felicia Metcalfe, one of the characters alluded to a house which, he said, reminded him of a Swiss chalet I he pronounced it shallett), whereupon another character retorted that it reminded her of a Swiss cheese. A couple of minutes later, one of the characters exclaimed, "I've got an idea!", to which another, feigning astonishment and incredulity, ejaculated, "No! Thirty seconds later, one of the characters referred to an Italian count, whereupon another observed that he'd bet he was no a-count. Later on in the proceedings, when it was established that the count was the genuine article, one of the characters allowed that "he always counted with me." The aforesaid count, I perhaps needn't add, was not without the inevitable white spats. He had been brought on to Baltimore by the young girl heroine, to stay with her family, directly after she had been briefly introduced to him at a wedding party in Philadelphia.

The stage director of this great master-work, one Roberts, like a number of other stage directors of the season's early exhibits, had evidently spent his life in the sole company of actors, in and out of greasepaint, and consequently quite naturally directed all the characters in the play out of their characters and into the semblance of actors. There was, true, hut little of characterization in the author's script, yet what little there was the directing gentleman eliminated in converting the actors into actors twice over. It would be a benefit to the theatre if many of these soi-disant directors would take a day off now and then, walk out of the stage door, stand on a street corner for a little while, and casually study a few' human

beings. The Blue Widow, by Marianne Brown Waters proved to he another humdinger, falling under the general heading of what, long since, have come to he known as "widow comedies." I haven't the statistics at hand, hut it is my guess that, excluding foreign importations and even the late Avery Holywood figures, we have had in the last twenty years of American theatrical history fully five hundred plays of this particular species. There is little variation to them. Either the widow is a lady regarded with a certain amount of suspicion by the other women in the cast—there was that rumored affair with young Travis in Egypt, you will recall—or she is a lady whose quiet, worldly manner and easy sophistication (expressed in gently ironic remarks which are taken by the other women to be of sweet import) eventually make all the latter, who have been estranging their lovers and husbands, see the error of their ways. At other times, the widow, all honey on the surface, is a shrewd schemer underneath, or a playwright's mere repository for some feeble paraphrases of Wilde epigrams. But whatever she is, she is certain at the conclusion to capture through her w'iles one or another desirable male in the cast upon whom one or more of her rivals have exercised an eye. Also, whatever the nature of the play, there is sure to he one scene in which the widow stands beside a piano and, toying with a long chiffon scarf, wistfully sings a little ditty, concerned either with amorous romance or, if the play he of a slightly saucy cut, with esoteric boudoir

(Continued on page 66)

(Continued from page 44)

The Mile. Waters' contribution to the lack of joy of nations was composed for the most part of the recognizable stencils, including the husband whose wife doesn't understand him and who is therefore a come-on for the clever widow, the elderly, opulent and vain goat who mistakes the little widow's wide-eyed, baby-pouting gold-digging for genuine affection, the man-of-the-world who knows of the widow's past, together with his share in it, but does not betray her secret, etc., etc. The manner in which the play was written suggested that the author had studied playwriting in Berlin about thirty years ago when the idea of an amusing popular comedy was to pair off the characters for two consecutive hours and have each pair successively repeat exactly the same scene. The stage director, one Winston, sharing the technique of his brother, Roberts, mentioned above, not only turned all the characters into actors given to the standardized actor comportment but, in addition, registered the play in so slow a tempo that he would be a wow if he ever went to China.

Just mentioning something called Crucible, by D. H. Connelly, and something called The Sellout, by Albert G. Miller—in both cases for no sufficient critical reason that I can think of— we come to Murder at the Vanities, by the MM. King and Carroll. The apparent ideational springboard for the projection of this one was the theory that if a musical show usually draws trade and if a mystery play usually draws trade a combination of musical show and mystery play ought to pack them in to the roof. That there may be something to the theory I do not doubt, provided, that is, that the musical show part of the entertainment is good and the mystery play part even better. In the case of the present exhibit, neither part was good enough.

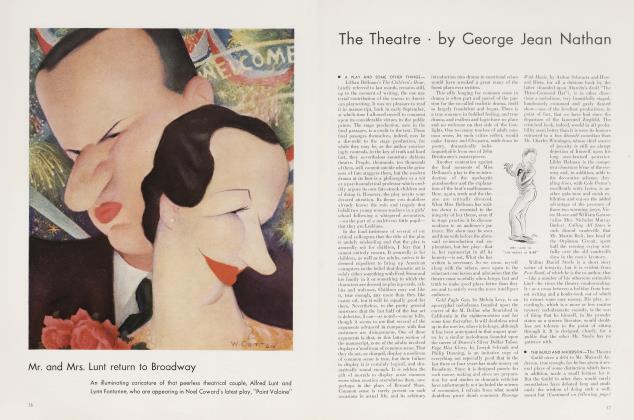

A TURN TO THE RIGHT.—As the season has progressed, however, certain of the more astute and experienced producers have proceeded to demonstrate to the theatrical recidivists the folly of their ways. The chief item on their blackboard is O'Neill's newest play, Ah, Wilderness!, revealed, with the matchless G. M. Cohan in a conspicuous role, by the Theatre Guild. Here we have a photographically true comedy of a thoroughly recognizable American household of the early nineteen hundreds dipped in the developing acids of a sure, sympathetic and amused dramatic imagination. There will he some, I take it, who—still laboring under the critical superstition that what makes one smile, and smiling chortle, can never be as important as what makes one feel cousin to a grave-digger—will assign the play to an inferior position in the catalogue of its author's accomplishments. But this gHfsame play seems to one who doesn't feel quite that way to be one of the best, one of the most humanly deep, and one of the most heart-filled things that O'Neill has written—even if, as the fact is, he tossed it off in less than a month's time.

For the last ten years it has been the local critical patois that George Kelly is first and foremost in the dramatic treatment of such homely family materials as Ah, Wilderness! contains. As one critic, I have never been able to share my colleagues' uniform opinion as to Mr. Kelly's great virtues. That he has some virtues, and of a very definite kind, is readily to be allowed; but that, as a dramatist in his chosen field, he has hulked as large as his friendly commentators have insisted, I have never been able to get myself to believe. I find some little satisfaction, as a consequence, in the fact that in Ah, Wilderness! O'Neill has written not only what falls into the reviewers' pigeonhole as "a George Kelly play", but that at the same time he has showed Kelly and his endorsing critics just what a so-called Kelly play should really be.

The story, as has been noted, of a typical American family of some twenty-five or -six years ago, the play pretty well justifies its folk comedy sub-title. There is not a character in it that isn't more or less familiar in retrospect to almost anyone who lived in and knew that period. Here and there, there is a slight touch of exaggeration, but such touches only point the integrity of the characters the more. To the whole, there is a family album and old tintype quality that is unmistakable. There is a bit of every now grown-up boy's father in that stage's father, as there is a bit of every such hoy's mother, and uncle, and brothers and sisters. There is also a hint of every such boy's first love affair, and of his first timid adventure in sin. and of his first brave, manly struggle with alcoholic liquor. That autobiography has figured in the O'Neill record is as certain as that it figures in the audience's memory.

As I predicted in my little piece on ONeill in these pages last month, it has come as a surprise to many that O'Neill had it in him to write such an amusing comedy; one containing as many, if not more, legitimate loud theatre laughs as any first-rate comedy by a professional comedy writer seen hereabouts in a long time. Why it should be a surprise, as I then suggested, I don't know. It is beside the point to repeat that in certain of O'Neill's antecedent work we have had evidence of his humor. But it is less beside the point to call attention again to the silly critical idea that, because a dramatist writes gravely on grave topics, he must arbitrarily be devoid of the comic gift. They thought it, in his time, of Björnson, and for more than twenty years, until he proved to them that they were fools. They thought it of Hauptmann until, disgusted, he quickly seized them by their donkey ears and gave them a couple of first-rate comedies within a period of eleven months. They thought it of Synge until he made them unbelieving of their own eyes at the spectacle of The Playboy of the Western World. They are always thinking it. In this play O'Neill has abandoned temporarily his avid experimenting with complex new dramatic forms and has worked in the simplest and most forthright. As one of his critics, I am glad to observe the happy and eminently satisfactory result, for it seems to me that there is sometimes an arbitrary and faintly strained effort on his part to evolve a new and strange dramatic form where the more conventional and established form would not only serve his immediate purpose just as well but even, perhaps, a little better. After all, when all is said and done, most of the fine plays of the modern theatre are found to have been written in the simplest manner.

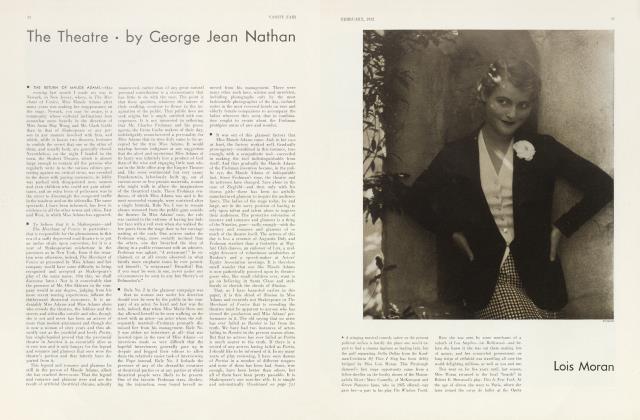

INCIDENTAL NOTE ON ACTING.— Studying the acting performances in the various exhibits reviewed above, one encounters an almost uniform deficiency on the part of the players. I allude to what may be termed the business of looking. While we always hear a great deal about the business of listening—that is, the convincing quality of an actor's attention and absorption in what is being said to him by another actor—the equally important business of looking—that is, a coincidental ocular attention and absorption—is seldom if ever remarked upon. Among all the players figuring in the plays described in this paper, only George M. Cohan is in this regard believable and impressive. The rest listen more or less effectively, but none of them has learned the trick of coordinating eye and ear. There is not a woman on our stage, incidentally, who couldn't profitably take lessons in this business of looking—hearing and ingesting with eyes as well as ears— from the young girl in the films named Loretta Young.

It is only recently, in point of fact, that the art of looking has received the slightest attention from our directors. And apparently with little success. The younger players do not seem to be able to catch the trick and, as for the old-timers, most of them still have "star eyes", eyes so vain of their owners' personal importance and theatrical eminence that they decline to lower themselves so far as to see (histrionically) any lesser person in the cast who is addressing them. The late Mrs. Fiske, you will readily recall, was a leading offender in this department. It was her acting custom not only never to give any sign that she ever heard what another character was saying to her but, in addition, to look at everyone on the stage as if he (or she) were a complete and rather odious stranger, and smelled a little to hoot. Ethel Barrymore doesn't go that far, but she nevertheless gives one the impression of never seeing anyone who is speaking to her unless it be the leading man, and then her ocular appraisal of him has less to do with him as a character than with the kind of collar and necktie he happens to be wearing. So with most of the others, excepting Margaret Anglin and Grace George, the only two older players who do anything at all about "looking" with interest and conviction.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now