Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Theatre

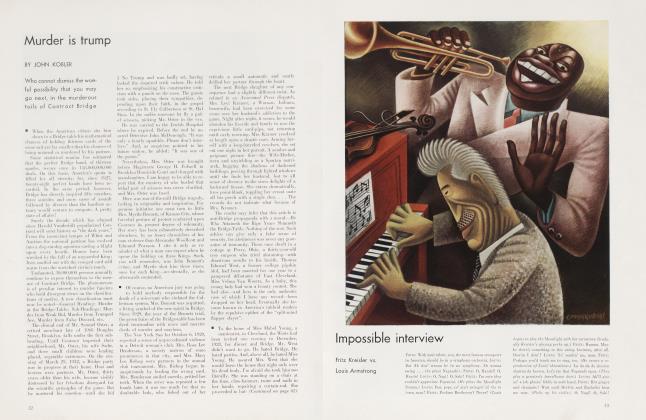

George Jean Nathan

BUSINESS OF LAUGHING.—It is a shame to take money for any such ignominiously juvenile remark, but a play whose sole primary objective is laughter is to be esteemed in the degree that it evokes laughter. By that standard First Lady, by Katharine Dayton and George S. Kaufman, is a considerably less successful performance than the Spewaks' Boy Meets Girl. It has, to be sure, that politer aura which customarily cozens the more injudicious critic into confounding manner with matter, and it offers, in addition, that filigree of suave malice which is theoretically supposed to transform any Joe Miller into an Oscar Wilde on the spot, but put it beside Boy Meets Girl on any honest critical scale and it becomes embarrassingly outweighed.

This Boy Meets Girl, although it ostensibly aims at an æsthetic target no higher than the diaphragm and although it has the deceptive air of mere lunatic jocosity, is— even aside from its lush comic attributes— a better intrinsic job than First Lady. Its character drawing is truer; its plot manipulation is a deal more dexterous; and its humor is infinitely more guileless and less strained. The comedy of First Lady, excepting perhaps a couple of scenes between the two women rivals for Washington social-political eminence, is generally in the Algonquip style: the straight line followed ceaselessly and unsparingly by the inevitable wise crack. The impression one gets, accordingly, is that the characters all talk as if they were habitues of the Algonquin hotel who were on their way to pleasing contracts as gag writers at the MetroGoldwyn-Mayer studios. The comedy of Boy Meets Girl, on the other hand, which incidentally deals with a pair of Hollywood gag scenarists, is so definitely in key with character and so a part of particularized character that it bowls one over with a double-barrelled force. No funnier exhibit has been seen hereabouts in a long time.

In First Lady, which engages the talents of Miss Jane Cowl and Miss Lily Cahill in the roles of the two political backbiters, no effort has been spared to belasco the proceedings into an aspect of manuscript size. But all the expert direction of the adroit Mr. Kaufman, all the handsome stage settings of Mr. Oenslager, all the dressmaking art of Henri Bendel, Marcel Rochas and others, all the corsages by the Universal Flower Co., all the jewelry by Jay-Thorpe, all the drapes by I. Weiss and Sons and all the lovely light fixtures by the Tudor Art Co.—to say nothing of the fancy shoes by I. Miller and the gleaming silver service by Henry Nord—cannot conceal the machine-made and calculating air of the script or the critical feeling that, whatever it started out to be, it has finally been introduced to us with a hat by Tyson, a chemise by McBride, and shoes by Leo Newman. It is, in short, a respectable good business man just a little ashamed of the fact and posing as the connoisseur of a dish of caviar and an oil painting.

The pair of actresses named do much for the play. Miss Cowl, perhaps more than any other of our American women players, has the gift, when the occasion demands, of concealing an intrinsic vulgarity of dialogue in the politeness of her delivery. In addition, she is pretty generally happy in retailing the lines of a comedy as if she herself were making them up as she goes along. In view of many of the lines provided for her in the present play this, true enough, is no particular flattery, for the authors' idea of smart humor is at times rather disingenuous. Of Miss Dayton's reputation as a wit, I know nothing, but her collaborator, Mr. Kaufman, has amply proved in the past that his brand of verbal frolic is superior to the species of stuff which is articulated in First Lady. Surely there is little that is commendable in such shabby attempts at humor as "Her nostrils positively breathed fire—you could have cooked crepes Suzette over them," "I think that was the Persian minister. No—Turkish. Anyhow, one of the rug countries," and "She had the most beautiful crest—a gorgeous crown, and unicorns sitting on sweetbreads."

To return to Boy Meets Girl. Here you have one of the most expertly cast and directed plays in several seasons. George Abbott's hand in such specimens of drama is usually very deft. While it is entirely possible that in the somewhat loftier ranges of dramatic art we might find him casting Madame Nazimova as Ophelia, and directing the play in the pace of Charley's Aunt, or assigning Mr. Noel Coward to the role of O'Neill's Hairy Ape, directing the exhibit in turn as if Barney Oldfield were chasing the author around a track, his aptness with such present-day scripts as have an air of having been written on a bicycle remains in no doubt.

That the central figures in the play are drawn from Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur, the authors are futilely cautious in denying, inasmuch as almost everyone who knows that indecorous duo (including the duo itself) freely recognizes a close identity. The authors, indeed, despite their denial, have actually transcribed more or less literally several of the twain's more celebrated Hollywood didoes. But the authors are hardly in need of a polite alibi, as Hecht and MacArthur themselves, in their plays and novels, in their moving pictures and short stories, have generally made large mock of both their living friends and enemies.

Among the ingenue performances in the current theatre none is so exactly right and at the same time so immensely amusing as that of Miss Joyce Arling as the Hollywood Serena Blandish. In the role of the young female moron who can't keep anything to herself, including the fact that she is carrying an impromptu baby, she maneuvers with unusual persuasion an utter vacuity into a kind of helpless tenderness and an almost burlesque bewilderment into a kind of legitimate psychical conflict. Her combination of Serena and Anita Loos' Lorelei, with slight added touches of Stanley Laurel, allowing full credit to her authors and doubtless also to her director, is a lovely job. But all of the others—few of them hitherto known to the local theatre—are almost as good. Allyn Joslyn and Jerome Cowan as Hecht and MacArthur, Royal Beal as a super-idiotic movie executive ("I'm the only college man in the studio," he observes proudly. "And they resent it."), Charles McClelland as a ham "Western" screen hero, and the rest prove that when other producers groan loudly over the exorbitant salaries they have to pay wellknown actors if they wish to cast their plays rightly, those producers only confess their own lack of initiative and judgment in getting even better unknowns, as Mr. Abbott has, for perhaps one-fifth the amount of money.

THE NEWER TALENTS.—The above remarks lead us naturally to a contemplation of the new, or relatively new, young talents, both among the girls and the boys, that have appeared upon the local stage thus far this season. Let us consider the girls first. Doris Nolan, in Night of January 16, although the recipient of some pretty blooms from the critical gentry, seems to have a modest equipment for obvious melodramatic roles but, beyond that, not much. She may develop, but her current performance is corrupted by that spurious physiognomic intensity favorite of Wampus Babies in their first roles showing them anticipating something worse than death at the hands of some night club gangster or Charlie Chan, and also by a self-consciousness equalled only by that of a dramatic critic at Mother in a tail coat. Doris Dalton, seen at the end of last season in Petticoat Fever and this season in Life's Too Short, has an excellent stage presence, a considerable deportmental and physical grace (particularly when sitting, which is a rarity with our young women players), and a pleasant speaking voice. Her height may be a handicap, as many of the better younger male actors, to say nothing of some of the older ones, are considerably this side of six feet.

Julie Haydon, the very lovely young person who appeared in Bright Star, plainly needs more experience. She is still nervous and ill at ease on the stage, all clearly demonstrated by her constant uncertainty as to what to do with her right foot when in a standing posture. She needs, more than anything else—and far more than personal study—a director who will dismiss her indisputable beauty as of second importance and who will talk to her like a Dutch uncle. One can feel a talent in her that may one day blossom, but it needs a directorial walloping to give it the right course. Tucker McGuire, which is hardly a name after the Hollywood glamour school, was revealed to us in Substitute For Murder and indicated an unusual naturalness in speech and comportment. There is, too, a fresh and artless manner about her that reminds one of the young English actress, Jessica Tandy, in her earlier performances. But she should diet. Mary Rogers, daughter of the late lamented Will, not only has much of the same naturalness and ease but an added sense of inborn theatrical spirit. Thus far, she has had the misfortune to appear only in cheap and trashy stuff. And nothing can so quickly ruin a promising young player as cheap and trashy stuff. She will have to watch out.

Elspeth Eric, in Dead End, has emotional intensity but doesn't yet know how to handle it. She begins a scene of violent emotion at such a pitch that when it is threequarters over she is able to do nothing more with it. Barbara Robbins, seen most recently in Abide With Me and perhaps not legitimately to be included in this catalogue of newer players—she has been acting hereabouts for several years—has proved in previous performances that she has a talent above the general younger run, especially in roles bordering on the tragic. Something of a studied chill, however, seems to have crept into her playing since then, which is to be deplored, as she is an actress who, if properly handled, should have a future. Marie Brown, who made her bow in How Beautiful With Shoes and whose pulchritude was not lost upon my fellow pundits in the art of histrionic criticism, is apparently a sensitive little thing but one who will need a wealth of training before she is ready for anything important in the way of dramatic roles. Dorothy Hyson, the young English girl who appeared in Most of the Game, has a number of qualities that fit her for polite drawing-room comedy, among them poise, style and the suggestion of the feeling that, as a youngster, she must have had a good governess.

Margo, the young Mexican girl who has already achieved a reputation as a dancer, and also as a screen player under the guidance of those two Astoria sons-of-Lubitsch's, the MM. Hecht and MacArthur, indicates in her first dramatic role (Winter set) that she has in her the stuff of a potentially authentic actress. She has the inner temperament and slumbering flame that most of our young Broadway Nordics so completely lack; she has that vocal sullenness that is so strangely compelling in the theatre; and, through her training in the dance, she knows what to do with her body and her hands. With more experience, a still missing shading and variety in the reading of lines should come to her. Beatrice de Neergaard, in Squaring The Circle, has evidently fallen so greatly under the spell of Elisabeth Bergner's performance in Escape Me Never that, if she doesn't look out, the Gerry Society will get her, and Fraye Gilbert, in the same exhibit, while possibly available material for some painstaking director, is so arbitrarily disposed to adopt the air of a tragedienne, whether the immediate occasion calls for it or not, that the effect is sometimes like Nance O'Neil holding hands with Jimmy Durante.

Polly Walters, late of She Loves Me Not and more recently in The Body Beautiful, has become the rubber-stamp Hollywood baby ingenue. Hancey Castle, in A Touch of Brimstone, reads clearly, has an agreeable stage manner, and suggests the lady, but what she can do in the way of acting remains still in doubt, as the two feeble plays she has been in have offered her neither help nor resistance. Doris Dudley seen in The Season Changes, hints of things and has a full share of charm.

As to the boys, omitting those already mentioned in connection with Boy Meets Girl, Burgess Meredith, in Winter set, again indicates that his is by all odds the best talent among the younger male actors. Myron McCormick is another lad who shows promise, his work in three successive plays this season—Substitute For Murder, in which he had a comedy role, Paths of Glory, in which his role was straight dramatic, and How Beautiful With Shoes, in which he played the character of a demented dreamer—proving that he has an equipment unusually varied for a player so youthful. Elisha Cook, Jr., who gave a creditable account of himself last season in Ah, Wilderness!, went completely ham in Crime Marches On. Joseph Downing—I don't know his age, but he is new to me— gives an admirable performance, exact in the smallest detail, as the gunman in Dead End. Theodore Newton, in the same play, shows nothing the one acting way or the other in the role of the cripple. Jules Garfield, in Weep For the Virgins, indicated that he is worth some critical watching, and James MacColl, whom I forgot specifically to mention in reviewing Boy Meets Girl, rates as an available candidate for future young romantic roles. Shepperd Strudwick, who started out so ably a few seasons ago, in Let Freedom Ring still shows a certain amount of talent but also an increasing artificiality. The youngster, Frankie Thomas, in Remember The Day, has much that is commendable for one so young but also a suggestion of precociousness that his father, the experienced Frank Thomas, Sr., who is in the same play, should promptly spank out of him.

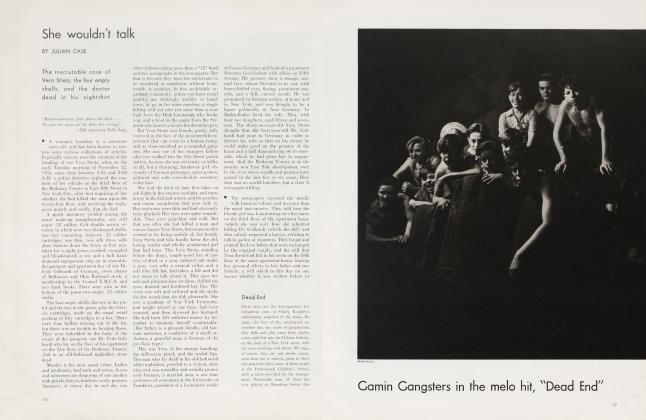

And then, of course, there is that truly remarkable set of kids, all under fourteen, in Dead End. Their names are Gabriel Dell, Billy Halop, Huntz Hall, Bobby Jordan, Charlie Duncan and Bernard Punsly, and they make one scratch one's head and wonder just a little about this whole business called the art of acting.

(Continued on page 63)

(Continued from page 46)

ODETS' LATEST.—Mr. Clifford Odets, last year widely proclaimed by the official proclaimers to be the young hope of the American drama, now causes his whoopers-up some faint concern. His newest effort. Paradise Lost, shown by the Group Theatre, is, it seems, hardly what they expected of him, although their disappointment is couched in terms that seek slyly to conceal their previous overwhelming critical exuberance. There is no need, however, for any undue disconcertment on their part. In this new exhibit of his, Odets again clearly demonstrates the possession of all the unusual qualities which he demonstrated in his antecedent efforts and which evoked their ecstasies. The simple critical fact is that, together with these unusual qualities, he again also clearly demonstrates his weaknesses and defects which, in their uncontrollable ebullition, they neglected to perceive in those other plays and which now, somewhat belatedly, they have become uncomfortably conscious of.

That Odets has a share of real talent no one can gainsay. But that it is as yet insufficiently mastered and orchestrated into sound drama should be obvious. His faults were every bit as plain in Atvake and Sing, Till the Day I Die and even in Waiting For Lefty as they are, now, in this Paradise Lost. He can write sharp, true, electric dialogue; he can feel passionately and he can convey that feeling; he has a good sense of character; he has eloquence; and he has that attribute so vital to the true tragic dramatist, pity. But he can also —and at times close upon heel—write bogus theatrical dialogue; he can feel and convey a greasepaint passion; he can sophisticate character to stage ends; he can be spuriously eloquent; and he can smear pity like mustard on what is essentially dramatic ham.

In Paradise Lost he admittedly attempts some Chekhovian dramaturgy, but Chekhov is as far from him as Pirandello was to B. M. Kaye a month or two before in the equally admitted effort called On Stage. He pursues the Chekhov elliptical method and futilitarian scheme with such a vengeance that the ellipsis and the futility get the better not only of him but of his characters, and in desperation at the end he struggles vainly to gather the threads together and achieve a lastminute-to-play centrifugal goal with a suddenly tacked on panegyric to the future of man that sounds like an O. Henry twist brewed from Shaw's Too True To Be Good last act curtain out of Chekhov's Trigorin. Here and there, a scene attests to Odets' independent vitality; here and there a slice of dialogue attests to his fine fire; and here and there, despite the banality of his radical utterance, his old passion sings its ringing song. But the amateur still goes arm in arm with the man who may one day be a sound and important dramatist.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now