Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowGolden swank

ALLENE TALMEY

An account of the rise of two night club impresarios through the judicious use of the Social Register

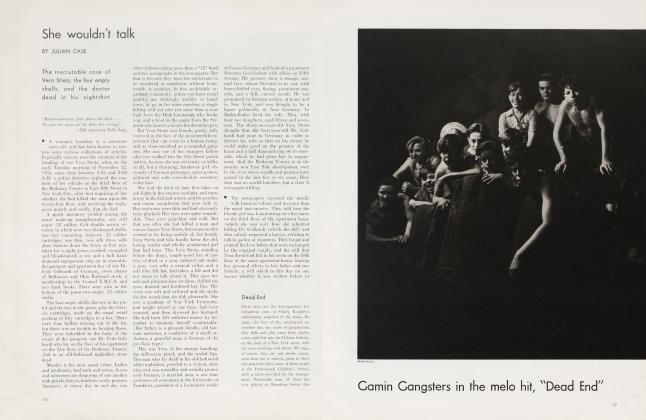

Nightclubs these days are rancorously shooting off in so many directions that the wisest gangsters refuse to invest in so shaky a business. No fat-faced Dutch Schultz backs the Rainbow Room at Rockefeller Center. No Owney Madden, small and honey, cuts himself unasked into the profits of the Persian Room at the Plaza. No Larry Fay, with horse-teeth, a big black hat, and a record of forty-six arrests, runs the Weylin Caprice Room. No Johnny Irish complains to his headwaiter that in this damp weather all his bullet holes hurt. Those strings of Prohibition nightclubs, owned by the Fays and the Maddens, are gone. Only occasionally do their lieutenants pop up in hidden financial records.

When they do, they claim that they are present just to protect an old investment. Those gangsters who went into it in the old days took it on as a profitable side racket to their large scale bootlegging, their rum running, their hi-jacking. They never rose out of the business by the stern route of busboy, waiter, captain, owner. It is no racket for a gangster. The policy boys from Harlem, who came to Broadway for a bit, are gone. Big Bill Dwyer, a Madden lad, flopped as a partner of Zelli, and only John Bagiano, who once had a hand in Greenwich Village beer deliveries, is happy with his interest in the Versailles. Most of them are willing to back out gracefully, leaving the field to the hotels, to the Rockefellers, and to two gentlemen, suave relicts of Prohibition. They are John Perona and Sherman Billingsley. Their business talents, devoted for years to a sly mockery of snobbery, now flourish with the Social Register. None of the dozens of little speakeasy fellows, who rose to be broken on the rack of grafting agents, had the flair of those two for the right set.

Now in their forties, they are columns of respectability. What diffidence they have can be discerned only in their eyes, the soft blue of Billingsley in the pink cushion of his face, the brown pebbles of Perona in his lean hardness. They walk with matronly dignity, secure in their elegance. Sherman Billingsley's scrubbed Middle Western brightness keeps his Stork Club seething. Over in the dumps by the Third Avenue Elevated, John Perona runs El Morocco, the smartest nightclub of them all.

Society is their game these days. The men with the social sense are the winners. Slowly they have built up an aristocracy of the supper clubs with photographs of their hand-made royalty in the social columns. Perona, of course, is the master. Even Billingsley admitted that, when Perona snagged for El Morocco the courtship of Barbara Hutton by Prince Alexis Mdivani.

His El Morocco at two o'clock on a winter's morning is a dream of a nightclub, smoky, stifling, with an electricity of gayety, starting from no known socket. Tables completely cover the dance floor, artfully arranged by Perona into a lovely cross-section of night club aristocracy. In clumps the debutantes sit, calling out from table to table, laughing their high whinny. In further clumps the kept women flash with diamonds almost as big as those of the society girls. There are always actresses, movie stars, models. Somewhere in the center wanders Perona with his sixth Scotch and Perrier, flashing his white smile, talking in his charming accent, which is neither Dago nor the English of Eton-bred Roman Princes. Obviously the jolly play-boy, laughing, gay, he talks in fashionable cliches.

There is little evidence then of the Giovanni Perona, born to a small cafe-keeper in Turino, Italy, who once batted back and forth on the London-Buenos Aires boats as busboy, steward, deck hand, until he met a big fat-handed fighter, named Firpo. When Firpo came to New York for the Sailor Maxted fight, Perona came too. Ho stayed. By the time Firpo returned for the Dempsey fight, the boy had his own speakeasy on West Forty-Sixth Street, filled with the sporting crowd. Deep in the smoke and the betting, Perona played practical jokes with an eye on the cash box.

A few years later he moved to East FiftyThird Street, setting up, with the exception of Jack and Charlie's, the most exclusive speakeasy of them all. He called it the Bath Club. With a suddenly developed social sense, he sliced off the top layer of the sporting crowd to take with him. The rest he left behind in the debris of Forty-Sixth. To the Bath Club came a newer, smarter crowd, more debutantes, more writers, more swank actresses. When he moved further East three years ago, he sliced again.

It was not until he had El Morocco about a year that Perona achieved the social rise for which he had been struggling. He staked his all on the blank little boys who were working hard on their reputations as men about town. At eighteen he let them run bills until they would come into their inheritances. Like an Oxford tailor he never duns. For that restraint they let him into their secrets, their loves, and their plans. He is confessor, advisor, and doctor to them. Like an analyst, he allows them to confide endlessly, charging only, however, for food and drink.

Some of them this year organized the Round Table. Every night, about fifteen of them eat at a big table with their President, Bill Plankinton, at the head, Perona by his side. These professional Peronites include Erskine Gwynne, Bobby La Branch, James and Woolworth Donahue, Dan and Bob Topping. So far the boys have thought of only three rules: two bottles of vin ordinaire on the table, no girls for dinner, no one in Plankinton's seat. The Round Table even has its own private telephone.

The boys are only part of the hundred and fifty regulars, the nightclub-going essence of the Social Register, who stop in every night, sometimes only for a single night cap before going home. On dull nights some four or five hundred come, on good nights eight hundred. After closing time, about five or six in the morning, Perona goes over the checks, seeing who the spenders are. Dinner for four, with cocktails, wine at dinner, and champagne later frequently runs up to sixty or one hundred dollars. Parties of eight often spend three hundred. The wily, who know the place, order his special Armagnac at $2.25 a pony.

Mugs never find out about the Armagnac. When they slip in by mistake, the headwaiter shuffles them hastily to tables by the kitchen's swinging doors. Waiters bump them, bring one drink at a time, get afflicted by waiters' blind eye. Although Perona has no cover charge, any order less than fifteen dollars for two may have a two dollar cover charge slapped on. If the management just doesn't like the faces, the cover charge may balloon to ten dollars a head. Perona is always too busy to hear complaints from the stuck. Their bleat annoys him.

While John Perona stays carefully in the light, his name popping up in the social chatter columns of the tabloids, his picture frequently in the Evening Journal, his brother, Joseph, remains in the background, running the kitchens and the kitchen staffs. A puffy gourmand, with a mouth for wine, Joe Perona knows no celebrities, casts no beamish eyes on the pretty girls. He watches the meat. While John flashes handsomely on a mounting wave of social advancement, Joe remains a highly irascible quartermaster, known lovingly as "Mother Superior."

Oddly enough, most of the money Perona makes in the winter, he squanders in the summer on his Westchester Bath Club in Mamaroneck. From an excess of energy, he constantly adds equipment, a badminton court, a pool, boats, an outdoor dancing floor. In faded blue shorts, and a maroon shirt, he lies every day by the pool, playing interminable games of backgammon, a long lime drink by his side. Surrounding him are the professional Peronites with, in addition, the clown or two he always has around. The butts of his gags, the clowns live on the place with no check ever presented. Of all, Peppino, a jolly tub of a man, is his pet. Unhappily, last year Peppino had a breakdown from the strain of exuberant crowds tossing him into the pool.

Of all the gags Perona ever worked, his most superb was the creation of Frank Busby. So constantly and so casually did Perona mention Frank that all El Morocco soon knew these salient details. Frank Busby had been born in South America. He was kidnapped by gypsies, and then adopted by an Indian Maharajah. Reluctantly Perona admitted that his friend was the richest and handsomest man in the world. "He is coming here," Perona casually said one night, "to buy up General Motors and distribute it to the poor."

On Mondays Perona usually relaxes from his week-end strain by racing down to his two-hundred-and-sixty-acre farm in New Jersey with its rambling Colonial house. There he cooks for himself, rows around on his enormous artificial lake. He keeps three boats there; three more on the Sound. When he drives himself, incidentally, he chooses out of his stable of eight, the Austin; likes to have his chauffeur, Confucius, drive him in the Cadillac. Every other year he goes to Europe, mainly to buy his clothes from Caraceni, the best tailor in Rome. Behind him, he leaves his wife and children to live quietly in a mild Jersey suburb, far from the farm and El Morocco.

Far different is Sherman Billingsley's place. He loves the mugs,—the right mugs, mugs who write, fight, and are in the papers. They are the backbone of his business. They come in delighted squads to the Stork Club, just off Fifth Avenue. Behind its fresh white limestone façade, the Stork Club makes no blunt pretenses. Guests run right into the enormous square bar, where three ripe lushes, like a set piece on a Victorian mantel, drink all night. What no one sees is the watchful man in the balcony, checking on the bartenders through a slit to see that no liquor is snitched.

What everyone, however, does see is Billingsley, and his mild periwinkle eyes, a deep blue flower in his buttonhole, stopping by the tables. He whispers in his soft voice, rasping like a well-oiled saw. With everyone he has a secret joke, a flicker of his eye-lid letting them in on a private lark. Too late, they find, as he moves on, he never told the secret joke. Billingsley relishes the dash of excitement here, the heat of people getting happily and gently drunk. When the pace dies off, he orders a brandy on the house for everyone. Sometimes it takes five or six free brandies a night to keep up. That dash of excitement, of course, brings celebrities. There are always a couple of fight managers, a bruiser or two, actresses, men from the track, movie producers, aviators, newspaper men, and enough society names for a bit of elegance in the society columns.

They are all there to be warmed by the ingenuous jollity of Sherman Billingsley, of Anadarko, Oklahoma, where there were only Indians and Billingsleys. By 1920 he had drug stores in the Bronx and four Bronx blocks of monotony known as Billingsley Terrace. Later he turned real estate broker, with his first negotiation a lease for a brownstone house on West Fifty-Eighth Street. His principals insisted that he come in with them. They were going to open a speakeasy, call it the Stork Club.

That private house became the first of the three Stork Clubs. It zoomed quickly into success. As soon as Billingsley found himself really running the place, he startled the trade by not charging extra for enormous blue bowls of celery, radishes and olives. He banked the bar with exposed bottles in an era when bar tenders just poured out a smoky liquid for any order of Scotch, from bottles under the bar. In Billingsley's place the customers named their brands and saw the liquor poured. He put down the first carpet in a speakeasy, advertised his illegality with a bright red canopy.

At that time Billingsley did not care for swells. He wanted the sports and the newspapermen. It all paid him well. After the Federal men, who smashed up most of his places, smashed up the first Stork Club, he put his profits into other peoples' clubs. He went halves with Tex Guinan, owned the Royal Box with Zelli, had an interest in the Park Avenue, the Zone Club, the Kit Kat Club, and the Club Napoleon.

Billingsley loves to run his places from the front. He arrives about five in the afternoon and stays until closing, doing everything for himself except the buying. That is Mrs. Billingsley's job. When Sally was the hit of the year, Mrs. Billingsley danced in its chorus. Now, still pretty, and exceedingly efficient, she buys for kitchen and bar. By now Billingsley has worked out a pretty system of running the place. He keeps a smiling blue eye on the waiters. If he notices one of them pushing, or arguing with the customers, he never reprimands. He sends the man a telegram, aimed to arrive at six in the morning. The telegram advises: "Be Nice to Customers." Waiters rush up constantly with notes. The Billingsley autograph stretches around the world. The only details he does not bother with are those of the checkroom, the outside doormen, the cigarette girls, and the ladies' and men's room attendants. From the concessionaires, to whom he leases those privileges, he receives some twelve thousand dollars a year. His rent, however, is only eight thousand.

Last winter he started out to catch the social crowd, but it was not until Marian Cooley opened her Thursday Nights that he really achieved a touch of elegance. Since then the bloods swarm the place. Just to prove, however, that he was not foolish, he took on Jockey Earle Sande, who, through with riding winners, sang moaning ballads through his nose. That publicity brought in mugs even from Hawaii, who took home with them the memory of Billingsley's chunky charm.

But mugs to Billingsley and Perona are merely the spine of their business, the fat and the fun lie in mass arrangements of Whitneys, Astors, and Vanderbilts. Theirs is an almost mystic flair for the nuances, the chiaroscuro, of the Social Register.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now