Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowParvenus in politics

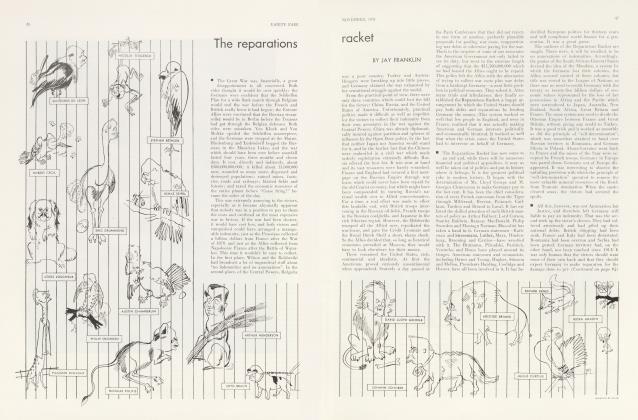

JAY FRANKLIN

Hell is popping to-night,

Our hearts are so bright!

Moley resigned to-day!

These unregenerate State Department verses (sung to the tune of "Bright Eyes") represented, with undue restraint, the general attitude of political Washington to the resignation of President Roosevelt's No. 1 Brain Trustee, Raymond Moley. It is doubtful that any one man has ever made so many political enemies in so short a time—and for no single assignable cause —as did the leader of Roosevelt's professorial coterie, the chief intellectual architect of the New Deal.

Because what happened to Moley is symbolic of the relationship between academic brains and political brawn in other departments of the government, it is important to examine the causes of this first success of the large and volunteer group of Brain Trust Busters in Washington.

The fundamental cause is, of course, the fact that an industrial democracy distrusts nothing so strongly as it distrusts the academic expert. Since Woodrow Wilson's eventful reign, the election of another college president as Chief Executive has been unthinkable. It is,indeed, altogether human to fear ideas and men of ideas, and when these ideas are advanced disinterestedly (which the general public usually interprets as irresponsibly) by a group of college professors, the average man has a feeling of panic, akin to that of the patient when the ether mask is slapped on his face and he is instructed to breathe deeply. For this reason, from the start, there was a large section of popular and political opinion, which regarded Roosevelt's "Brain Trust" as the weakest spot of the new administration.

Roosevelt and his hard-headed political advisers were exceedingly sensitive to this condition. They took pains to set a practical administrator in authority over each member of the Trust—Hull over Moley; Wallace over Tugwell and Morgenthau; Jesse Jones over Berle—and vigorously denied that the Trust itself had any real existence. Yet the torrent of radical legislation which Congress adopted gainsaid the official denials, while the appointment of such tough-minded organizers as General Hugh S. Johnson for the N.R.A., Secretary Ickes for the Public Works Administration, and George Peek for the A.A.A. could not conceal the fact that the measures they were appointed to administer were highly radical experiments, conceived in the scholastic test-tubes and matured in the academic libraries of the Brain Trustees.

With the rights and wrongs of permitting academicians to shape our national policies, the wise political observer is not directly concerned. To many of us it seemed a splendid thing to entrust, with the formulation of public policies, individuals who are not trying to line their own pockets or make soft jobs for the boys in the precincts or even to win the next election. To others, it seemed dangerously romantic to permit a few professorial parvenus in politics to dictate the conditions under which the non-collegiate mass of Americans must live and move and have their being. For the moment, all that is required is to state that the Brain Trust is responsible for the Bankruptcy Bill, for the Farm Relief Act, for the inflationary amendment thereto, for the plans to establish a commodity dollar, for the Muscle Shoals Act, for N.R.A., and for the other legislative peanuts and pop-corn of the New Deal.

This is a great political achievement for a small group of intellectual gag-men. For the real Brain Trust was exceedingly small. It actually consisted of Raymond Moley, Professor of Public Law at Columbia University, then Assistant Secretary of State, and now editor of Vincent Astor's new weekly magazine (known irreverently in Washington as "The Astorisk") ; of Professor Rexford Guy Tugwell, Professor of Economics at Columbia University, student of Soviet Russia, and now Assistant Secretary of Agriculture; of Adolph Augustus Berle, Jr., Harvard boy wonder, lecturer at Columbia, lawyer and student of corporation law, and now special adviser to the R. F.C.; and possibly of Henry Morgenthau. Jr,. son of Wilson's Ambassador to Turkey and head of the new central agricultural credit administration. Of all these, Moley was the greatest and great was his downfall.

Washington did not like Moley. Neither politicians, bureaucrats, nor newspaper men liked him. That was phenomenal, for Washington is a tolerant if cynical city, with more than a sneaking affection for its Huey Longs, Heflins, and Penroses. Moley's first mistake was in being assigned to the State Department. It has been said that even his best friends admitted that as a diplomat he left much to be desired. He belonged in the White House, as an Executive Assistant. Even so, the State Department would have tolerated him, had it not been for his arrogance. Fundamentally modest, it was his misfortune, politically, to possess a good brain and to know it. He realized that fact too keenly. He constantly showed people that he realized it. He was not a good subordinate and his constant popping over to the White House, on the President's summons, prevented him from either handling his Departmental routine or becoming acquainted with his subordinates or his Chief. The casual manner in which he was given the handling of war debts and was sent to the London Conference irritated the diplomats who had spent years of expert study on the problems.

(Continued on page 58)

(Continued from page 18)

The politicians did not like him. Suffice it to set down the fact. Later on will be the occasion for a discussion of their instinctive hatred of this self-confident parvenu. Enough to say that never once, during the course of the campaign or afterward, did he conceal his honest contempt for "practical politicians."

The newspaper correspondents loathed him. It was not, as his friends and fellow-trustees imagined, because he competed with them in his writings for the press. That was set down as a perfectly admissible if irritating form of political propaganda for the Administration. It was just that they didn't like him. When Drew Pearson wrote a story which commented on his baggy eyes and baggy trousers. Moley told his next press conference that his eyes were baggy because he worked late at night and produced receipted hills to prove that he had his trousers pressed regularly! When the newspapers commented on his actions in hiring a plane to fly to London and then not using it, and spending huge sums in Transatlantic phone-calls to the President at Campobello Island. Moley explained it all in a press-conference! The general reaction was: What a fool! The moral: Never explain anything!

Accordingly, Washington began to buzz with unfriendly rumors—is he retaining his salary at Columbia? Gossips talked about his legal adviser, bumptious young Arthur Mullen of Nebraska, with what seemed to be his artless desire to fire every career man in the State Department and replace them with deserving corn-belt Democrats; about his strained relations with Cordell Hull. The tone of his writings for a weekly newspaper syndicate was loo smooth to help him. When he praised Congress in his first article, Congressmen winced; when he returned from London with syndicated praises of Canada, even the Canadians grew uneasy. Foreign diplomats who had to deal with him began to speak of him (in private) as "Holy, Holy Moley."

(Continued on page 69)

(Continued from page 58)

Washington did not like him. When Hull returned from London it was an open secret that Moley would leave the State Department. There were tales of wire-tapping and espionage inside our delegation at the Conference which made the situation tense. Moley was hastily put in charge of the anti-racketeering drive at the Department of Justice, hut this was only a blind. Louis Howe in the White House decided that Moley's unpopularity was hurting the Administration. Howe, a practical politician of long experience, had never relished Moley's brief ascendancy in the counsels of Roosevelt, saw his opportunity and struck. Not Cordell Hull hut Louis McHenry Howe was the man who killed Cock Robin. This fact will he denied as vigorously as Moley denied that he was politically dead, hut it is accepted as gospel in the small group of insiders at. Washington. At any rate gossip had it that Moley was summoned to Hyde Park and given his walking papers, over a golden bridge created by Vincent Astor. The true story, however, seems to be that as long ago as last May, Vincent Astor and Mrs. Mary Rumsey went to the President, asking him if lie would be willing to release Professor Moley for an editorial job. At that time Astor was prepared to place a bid on the Washington Post for $552,000. The paper was later bought by Eugene Meyer for a price far in excess of this. Their desire and expressed intention. according to Mr. Moley's own wish, had been to make him the Editor. The plan to purchase a paper fell through, and shortly after that the idea of the Moley weekly was conceived. Therefore, the persistent efforts of the journalists to make it appear that Moley had been "given his walking papers" after his European debacle, while not the truth, serves merely as a further indication of Professor Moley's unpopularity and perhaps unfair treatment at the hands of the newspaper fraternity.

(Continued on page 70)

(Continued from page 69)

The same fate now threatens the other members of the Brain I rust. Tugwell will be the next target, but he will be more difficult to dislodge. In the first place, his chief. Henry Wallace, is his close friend; in the second. Tugwell has never publicized or advertised his relations with the President; and in the third place, his syndicated writings are free from that air of patronizing simplicity which infuriated political readers of Moleyana.

At the time of the bank holiday, Tugwell believed in letting the banks slay closed, irrespective of the sufferings of depositors, on the Napoleonic ground that you can't make an omelet without breaking eggs. Tugwell is responsible for the blasphemous slaughter of sows, the obscene destruction of wheat and cotton, in the hope that it will shock the people into demanding more fundamental remedies. "I don't trust that man Tugwell!" is the attitude of more than one Democratic politician. If food is scarce or unduly expensive this winter, Tugwell's head will roll in the dust. Hunger is impatient of brains and has its own reasons of State.

Adolph Berle is already under fire. this position of impartial arbitrator has been challenged by the American sugar refiners on the ground that he also represents important Cuban sugar refiners. They may get Berle sooner or later, on such grounds as these.

Here again, the real reason is akin to the reason for Moley's downfall— or dislike of intellect in politics. A similar dislike attaches to such men as Professor James Harvey Rogers of Yale and Professor George Frederick Warren of Cornell, who have been mysteriously closeted in Washington working out plans for a new tax bill, with a commodity dollar on the side; to Professor Irving Fisher of Yale. who has been consulting the President at Hyde Park; to Professor Sprague of Harvard, recently economic adviser to^the Bank of England and now special adviser to the U. S. Treasury; and even to Lew Douglas, Director of the Budget and father of the Economy Act. The distrust, everywhere, is not of their origin, their position. or their policies, but of their brains.

For politics is not a lecture in a class-room, not the brilliant demonstration of a self-evident or complex thesis; politics is the art of persuading human beings to cooperate. It moves in a twilight zone of half-measures, compromises, and consideration for human weaknesses. It speaks the language of the pants pocket and the clenched fist. The Brain Trust is no more fitted to direct this messy, misty process than it is fitted to run a department store.

The unpardonable sin in Washington is lack of common humanity, lack of that stupid streak, which enables a leader to understand the inarticulate and wrong-headed notions of ordinary men and women. The New Deal has been brilliant so far, but it has not been conspicuously humane, though avowedly humanitarian. Every politician—in fact every resident in Washington—is being deluged with appeals for assistance from deserving and undeserving individuals. But when these cases are brought to the attention of the Brain Trust, there is an extraordinary difficulty in finding any way in which to help them practically. When the New Deal comes down to cases it falters and approaches paralysis. We still have 12,000.000 unemployed and winter is almost upon us. Yet Donald Richberg at the N.R.A. is credited with having refused exemptions from his codes to charity restaurants, on the ground that unemployment would be wiped out and there would be no need for charity. Every man in Washington could tell you of innumerable cases—plain, refractory cases—for which the humanitarian legislation, for some reason, is unable to find the correct pigeon-holes. They ask for jobs and are given pamphlets, ask for relief and get good advice.

Political insiders in Washington know what they should do in these cases—stretch the law and give relief—but the Brain Trustees cannot blur the edges of their legislative pictures. Every good politician knows that exceptions must be made in every regulation and that a law is no good until it has been broken. The professors don't understand what made Abraham Lincoln pardon deserters and weep over the Union losses. They don't understand the essentially human character of politics. Politicians have seen the people take the recently omnipotent bankers for a ride and they suspect that the professors will be the next ones to be put on the spot. Hence the growing bitterness between the Brain Trust and the politicians.

That is the secret of the unpopularity of the Brain Trust, the downfall of Moley, and the threatened obliteration of the brilliant group of intellectual vivisectionists who dominated the opening months of the Roosevelt Administration. The gossip about their financial and journalistic peccadilloes has nothing to do with the case. Their intellectual arrogance and the rigidity of their schemes is of secondary importance. Their personal and political relations with their respective administrative superiors do not matter much. The real trouble is that they think above the pince-nez, whereas the best politicians think below the belt.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now