Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE EDITOR S UNEASY CHAIR

Staten Island enters art

H. E. Schnakenberg. a reproduction of whose painting Conversation appears on page 28. is one of tlie younger leaders of American painting. He was horn, of German and Scotch-English parentage, in a place all too sober for an artist: Staten island. His early years won him some business training and experience, but his artistic tendencies conquered and he began study, at twenty-one, at the Art Students' League of New York. The great Armory Exhibition of 1013 caused him to make up ids mind definitely to lie a painter. and lie became a pupil of Kenneth Hayes Miller, one of the most fruitful of progressive American teachers. He gave up two years in the middle of his studies serving the colors in France. Since the war lie has worked independently, doing most of his painting in Vermont. Frequent travels, to Europe and the South, bring him in contact with new subjects; he carries water-color equipment with him wherever he goes. He has had several one-man exhibitions in New York, and is represented in large collections including the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, the California Palace of the Legion of Honor, the Wadsworth Athenaeum (Hartford), the Whitney Museum of American Art, and the Addison Gallery (Andover).

Bermuda clarinet

Joel Sayre, author of the Profile of Owney Madden on Page 47 (a parody of the popular "Profiles" in The New Yorker) was born in Indiana when the century began, and made his début in literature with a column entitled "Fact and Fancy" in the Ohio State Journal. He enlisted in the army and served with it in Siberia (for about five minutes) ; he went to Williams College (for three months). The next ten years he spent writing advertising copy, school-mastering, and studying medicine. These got him nowhere, except to convince him that he was a newspaper reporter. He worked on the Herald Tribune under Stanley Walker, who, he says, ''managed and trained the greatest stable of newspaper men in the history of newspapers. There were Alva Johnston, Ishbel ltoss. Beverly Smith, Herbert Aslmry, Frank Walton, Hugh O'Connor, Allen (K.O.) Bengal) and Kichard (O.K.) Beagan, Ernest Lindley, Edward Angly, Allen Baynmnd. Horace Greeley, and scores of others." In 1931 he wrote a book on football and racketeering called Rackety Ra.r. A tract on municipal affairs, Mr. Mayor, Mr. Mugger, will be brought out this March. Now he resides in Bermuda. Becently. he says, he has taken up paternity and playing the clarinet.

Bored with Borah

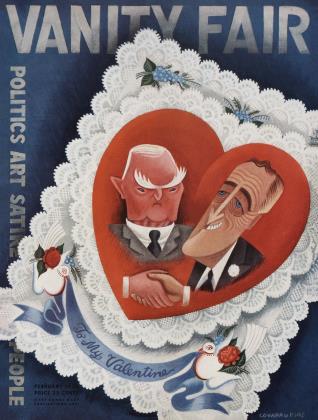

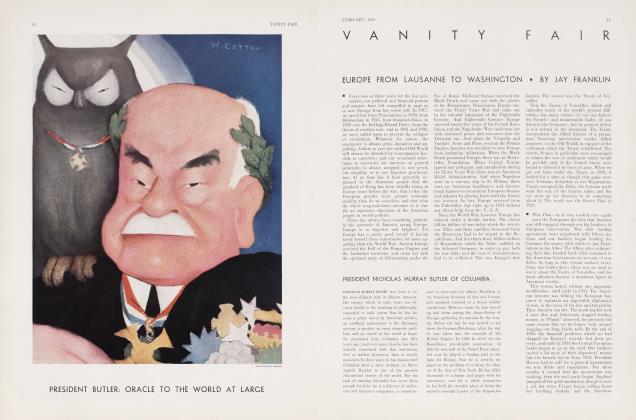

Hear Sirs: Your chief political caricaturist. Mr. William Cotton, Is a colorist of the first order. He is also of the first order in what the art critics call, I believe, "three - dimensional space - compositional plastic form." That is to say, he is a good artist.

But the question arises, is lie a good political thinker? Is lie a profound interpreter of the leaders lie depicts? Certainly he always succeeds in doing one thing, and that is making ids subjects look as though they were pretty decent fellows after all. He is a very well-mannered caricaturist. And perhaps he is a bit too impressed by tlie high station of the people he is immortalizing.

The Stimson caricature (December issue) makes Wrong Horse Harry look like a very dear and amiable soul. His cheek rests on the globe, and his right hand caresses it. One gets the impression that the retiring Secretary of State holds the whole world very dear to him, and is held very dearly by the world. The picture suggests, in other words, that he is a foremost internationalist. The picture is about the only tiling that ever has suggested that Mr. Stimson is an internationalist. To begin with, the excellent gentleman is a Republican. Ho has done nothing at all to bring America closer to Europe, to the League or to the World Court. He has pretty regularly been an exponent of the hoary old idea of avoiding "entangling alliances"—which is to say. of avoiding to help Europe in clearing tip those problems which affect us directly.

But let us not squabble on the old League question. In the January issue Mr. Cotton comes forth with a beatific vision of Senator Borah, Republican, from Idaho. He is labelled "the Twister"; but the editors very specifically say that "twister" refers only to the Idaho whirlwind, and not to Mr. Borah's facility as a political twister. Well, be that as it may. But still, Mr. Cotton makes the man look just too sweet and amiable. He wears a little frown, but it is nothing serious. He looks as though he were pouting a bit, but it's not really very bad. His eyes are clear, lie leans on the Capitol dome, and lie holds an official scroll in his hand: all is for the best. Mr. Borah is a very good and wise statesman.

Mr. Cotton overlooks Senator Borah's rampant dryness; his crusading self-righteousness; and, above all, his eternal bellowing and barking over practically nothing at all. He overlooks the fact that after a quarter of a century of presence in Washington, Mr. Borah has accomplished nothing except to make his voice the loudest, and his obstructionism the most obstinate, in the entire capital.

Perhaps at present Mr. Borah is not quite worth a frontispiece. Perhaps it would be good editorial policy never to use a Congressman before the twenty-fifth page of the magazine.

DONALD FAIKHUKST

Contrary evidence

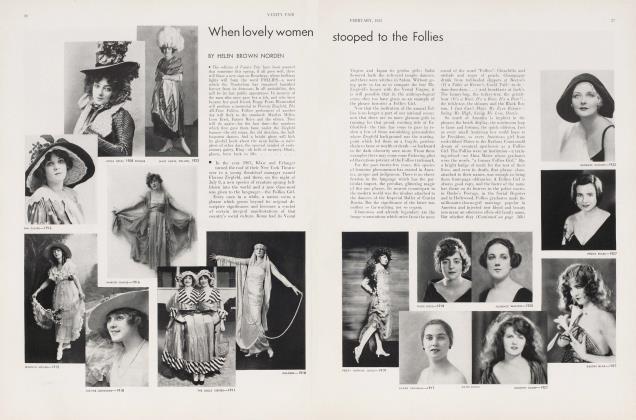

Helen Brown Norden, author of IF hen Lovely Ladies Stoop to Follies, on page 26 of this Issue, was born twenty-five years ago in LaFargovllle. New York. She was educated at Bradford Academy in Massachusetts, and entered Vassar, at the age of sixteen, on the Honor Boll. She says that at the time she was "considered a very bright girl, although later there was much evidence to the contrary." After she was graduated she spent two years as a reporter on the Syracuse Herald and two years as feature writer and dramatic critic on the Syracuse Journal. She has been on the staff of Vanity Fair fora year.

Let us have Doom

Dear Sir: It. behooves the author of So Many Doomsdays, in your December issue, to read some of the back numbers of Vanity Fair. His alert eye is bound to encounter in the issues that were published in this past year a strong tendency towards revolution. Of course, in its own well-bred manner, Vanity Fair confined its rebellious attitude to the front part of the magazine. But even in that space generally reserved for sartorial knick-knacks I discovered the subtle rumblings of uneasy to-morrows.

At one time I had the curious feeling that the magazine was on the verge of featuring the proper morning attire to be worn on the barricades which were imminent around the Graybar Building. If I recall correctly there was even some sort of abortive movement afoot to launch a third party.

I do not blame the author of So Many Doomsdays for having misjudged the modest efforts at satire of our magazine Americana. We have no program and no faith. The ultimate greatness of Marie Laurencin or the chaste finality of a well tailored morning-coat is adequately represented in the pages of your urbane publication. The New Masses is grimly bent upon publicizing its own kind of arid millennium. Between these two unintentionally humorous extremes we have set up our little portable shooting gallery.

Remember above all things that you too were young once, Mr. Hale, and recall that wise axiom of Goethe's: "There is but one thing more horrible than a young conservative, and that is an old radical."

However, I may have misjudged you. It is perhaps just barely possible that in some future article you will point out with equal facility and justice that all prophets of doom were right and that Rome. Judea. Carthage, Macedonia. Babylon and a few other more recent social units are no longer with us. Americana cheerfully anticipates the privilege of quoting from that article in the near future.

CHARLES D. YOUNG

Office of Americana magazine, New York.

Mr. Young's points are well taken. His hint about proper morning attire to be worn on the barricades expected around the Graybar Building has been passed on to our men's wear department. Already two schools of expert opinion have arisen in that office. The conservative wing holds to a belief in the formal morning coat, with white vest and Ascot tie. The radical wing, endeavoring to make concessions to freedom of life and limb, advocates semi-formal attire, with four-in-hand tie and a bowler. No member of the sartorial staff has come out for khaki shirts, open at the neck. Helmets, visors, gas-masks, and breast-plates are not being favored this season, despite all expectations to the contrary. THE EDITORS.

Despot of a daily

Stanley Walker, author of The Gnome Nobody Knows on page 24. Is only thirty-three years old. a Texan by profession and city editor of the New York Herald Tribune by circumstance. To the most cynical of professions he Is widely known as one of Its most adroit and ornamental practitioners. From the city desk of that newspaper he has collected one of the most brilliant staffs of news writers ever assembled and maintained It at a high level by feverish research into the ranks of oncoming bright young men, a continued exploitation of new talent made necessary by the circumstance that as soon as he makes a reporter famous somebody else buys him away from the Herald Tribune. He is a passionate collector of verbiage, encourages the use by his staff of such words as "curmudgeon," "fuddy-duddy," and "trend tinder," and has rehabilitated "dornick" as part of the English language. Although he has a large corps of assistants, he frequently takes the city desk for both day and night shifts running. He is always on duty by eleven in the morning and usually waits until the first edition Is off the press at eleven at night. He reads the paper on ids way home to Great Neck and when he arrives at once telephones an angry barrage of corrections and comment to the office. His youngest child, age two, Is being taught the rudiments of copy desk knowledge.

Continued on page 11

Continued from pace 9

Fee, fie, fo, fum!

Dear Sir: In your January Issue. J. Maynard Keynes, the English economist, offers a very plausible plan for the re-establishment of international trade, and the revival of world buying power, which, if successful, would ensure the cherished hope of millions—the return of prosperity. Mr. Keynes says: "The plan would be as follows. An international body—the Bank of International Settlements or a new institution created for the purpose—would be instructed by the assembled nations to print gold certificates to the amount of (say) $5,000,000,000. The countries participating would undertake to pass legislation providing that these certificates should be accepted as the lawful equivalent of gold for all contractual and monetary purposes. . . . This plan should appeal to those who wish to see the world return as nearly as possible to the gold standard, and also to those who hope for the evolution of an international management of the standard of value. I see no disadvantages in it and no dangers. It requires nothing but that those in authority should wake up one morning a little more elastic than usual."

Mr. Keynes Is to be congratulated on his optimism in seeing no disadvantages and no dangers in this plan. His plea for elasticity, however, will not be popular with treasury officials who have grown weary of the rubber checks of international credit. Moreover, Mr. Keynes' plan to stabilize international currencies, while unusually persuasive, is only another one of the many with which the forthcoming World Economic Conference will be deluged. And all such plans Ignore the trenchant and fundamental fact: that no scheme can for more than one brief and subsequently breathless moment stabilize international currencies while national budgets remained unbalanced, and national confidence in peace expresses itself in an international race to arm. First, nations must, individually, and through the peaceful methods of diplomacy, settle their differences. (Foremost among dangerous differences are those between Germany, France, Poland.) Realistic settlements of its own vexatious border problems would inspire, in each nation, the confidence of its own nationals in the security of the government. and the enduring quality of the present peace, which, at the moment, in many countries, is little more than an armed truce. This re-establishment of confidence would do more to turn the tide of the depression than all the economic nostrums which Keynes, Salter, Chase, et al. have propounded since the dark days descended upon us. Secondly, each nation must then ruthlessly and honestly balance its o~cii budget. Not until this onerous but vital chore is done; not until each nation has put its fiscal house in order, can all the nations of tlie world assemble about a conference table with the expectation of accomplishing anything of permanent value in the field of international relations. The chain of international exchange can be no stronger than its weakest monetary unit. . . .

Now, while this is not quite the place to reply to Mr. Keynes' effusion in the Herald-Tribune of December 11yh, as an American who lived through the days of the war on both sides of the Atlantic. I would like here to register my protest against the liritisli economy (with the accent on the British) which refers to tlie interest on tlie war debts as "pure usury". There Is always much to he said for. and by, the debtor, who finds it difficult to pay his debt. He Is never without excuses, seldom without reasons. And these always range from the moral to the economic spheres, and are measured with more emotion than logic by both spiritual and gold standards. Mr. Keynes' argument in his front-page bit of patriotic heart-ache (Ills emotion penetrated even Die cold mask of the economist) was that "there are not now, and never were any profitable assets corresponding to the sums borrowed. . . . The war debts are a case of pure usury, ..." Perhaps Mr. Keynes forgets tlie asset. Invisible hut not negligible, of tlie victorious, rather than defeated. Allies. Had England not been able to borrow money from tlie U. S. A. tlie war may well have ended with Germany triumphant, and, under these painful circumstances, of one thing we may bo certain: that England's economists would not now ho raising their voices In any cry of "usury". German Kultur would have permitted no such Illogical as well ns had-mnnnered outburst from the defeated.

Further, In this amazing newspaper pronouncement, Keynes Infers that America expected to make a profit out of financing (lie war. Tills Is an unjust accusation. After all, feudal king may lend to feudal king, helping him to finance his one man's war, expecting a "cut" In tlie booty, or prepared to lose Ills gambling stake In Empire, hut when a democratic government lends money, even with tlie greatest sympathy. It must be remembered that that government does not dip autocratic fingers Into a Roman Emperor's personal treasury It borrows from its individual citizens, from whom it would be unable to borrow if it did not pay them interest. Also under some misconception as to tlie nature of the ''sanctity of contract", and the "reasonableness of creditors", Mr. Keynes writes as thou lie had quite forgotten 1918, anti the mad corridors of Versailles. . . . The English were then the most unreasonable in making reparation claims from Germany. They were. Indeed, the authors of tlie pensions and reparations. Although it Is a long while ago. I am sure that the distinguished gentleman, Mr. Keynes, who was present at many of these fantastic little Versailles pourparlers, lias not forgotten that Ids own nation led in writing tlie mad formulae which included war costs In reparations. These "reasonable" clauses were prime determinants In the eventual settlement of the huge amounts which Germany was supposed to lie able to pay.

Mr. Keynes adds to his other slight perversions of consistency, the statement that "A final settlement In which wo (the British) alone were to make large payments In respect of war debts would be monstrous". It is, however. Into this very monstrous situation that Mr. Keynes would leave America, while Germany (whose quarrel was never our quarrel) remains freer of tlie consequences of war than any of the combatants and England, France and Italy bow themselves gracefully off the distressing scene. After which America, the only disinterested nation in the war, is called indiscriminately usurious, mercenary and uneconomic because she is disinclined to finance the whole show, forcing American taxpayers to be the unwilling "angels" for the calamitous European Follies of 1914!

In any case, it would seem that little progress cat: be made In the cause of international comity if men of the distinction and intellectual acumen of Mr. Keynes persist In aggravating tension by such ill-advised and illogical statements as to call the Interest on the debts which are owing the American people—"pure usury". . . . BOF.TIUS LUX

New York City.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now