Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Pulps: day dreams for the masses

MARCUS DUFFIELD

EDITOR'S NOTE: This article is the first of a series planned to deal with the magazines of America. It will he followed by discussions of the humorous magazines, the popular weeklies, the "quality" group, the liberal periodicals, and others.

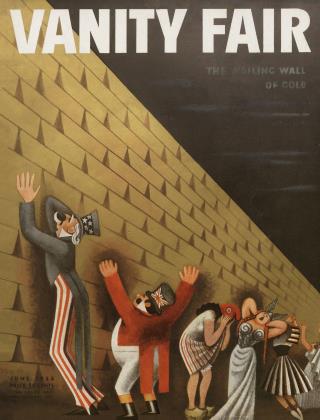

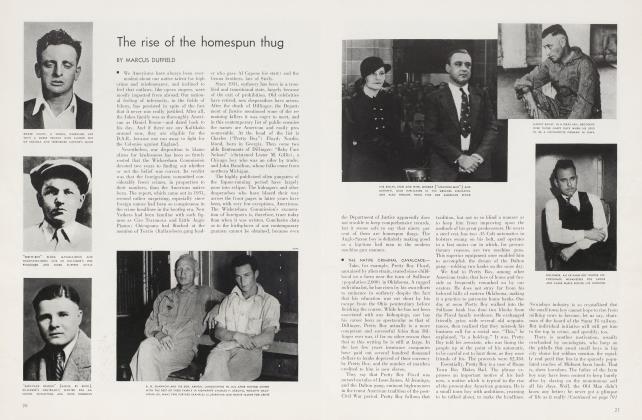

They swarm over the news stands, gaudy, blatant, banal: Wild West Weekly, Astounding Stories, Ranch Romances. They are the Pulps, fiction magazines that get their nickname from the fact that their pages are of the very cheapest pulp paper. Into this underworld of literature most of us never dive unless, like Mr. Hoover's Committee on Recent Social Trends, we are curious about the literary preferences of those who move their lips when they read.

The Pulps are lineal descendants of the old-time dime novels that the current elder generation read under haystacks when it was a hoy. The publishers of those paper-back thrillers used to experiment with magazines of the same intellectual level every now and then as far back as the 1880's. The idea was to reach out for that class of readers who lacked the staying power to read through an entire dime novel. A sound idea, out of which has risen a uniquely American institution; no other nation is blessed with Pulps like ours.

Among the forebears of the Pulps there was, for example, a magazine called The Black Cat, each issue of which was an orgy of gruesomeness. One of its star authors was a Judge Crandall, a gay dog who suffered nightmares. These he wrote up for The Black Cat. His doctor told him he would have a nervous breakdown if lie didn't stop, but he kept on, and later events bore out the doctor. This was a misfortune for the magazine because its readers had grown attached to the Judge's hallucinations.

The Black Cat has long since died. So have two other magazines, La Parisienne and Saucy Stories, which were put out by a pair of ambitious Pulp publishers named George Jean Nathan and Henry L. Mencken. Mortality rate was heavy among those early Pulps as, indeed, it still is. The veterans of all the Pulps are Argosy, started in 1882, and AllStory, in 1889, by a then unknown young adventurer in the publishing field who was later to do pretty well—the late Frank A. Munsey. Partly because of their unprecedented longevity and partly because of their slightly higher quality of fiction, Argosy and AllStory, together with Adventure, are today the aristocrats of the field.

After the War the Pulps enjoyed a fabulous boom, until at the height of their vogue in 1928 some twenty million persons read them every month. All of these eager readers had to seek out the magazines and buy them on the news stands, for the Pulps never have tried to build up home subscription lists. The circulation is somewhat lower now. both because of the depression and because of the rise of the rival movie magazines. But there are still some fifty Pulps, almost any one of which has more circulation than a "quality" magazine such as Harper's or Forum.

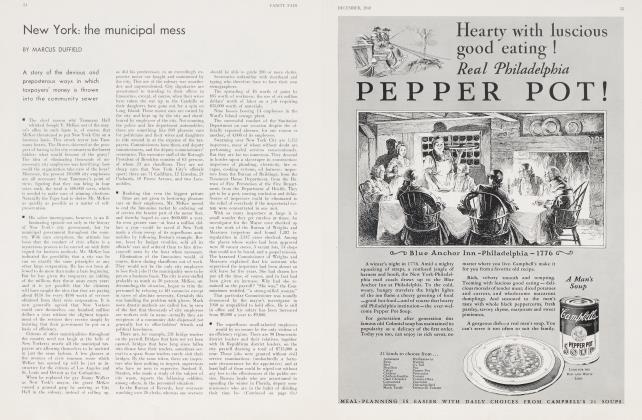

Miners, mechanics and quick-lunch dishwashers who find life dull have only to open Ranch Romances to translate themselves into hard-riding cowboys beloved of man and beast, saving the herds and heroines of Bar BQ Ranch. Chicago soda-jerkers living in tenements with their mothers and three snivelling little sisters are transformed into dare-devils of the sky merely by reading War Aces. Girls in Pennsylvania hosiery mills and Kansas City ten-cent stores find their handsome lovers in True Confessions. The Pulps manufacture day-dreams, on a wholesale scale.

The people who write Pulp stories are somewhat of a mystery even to the editors themselves, because they seldom sign their real names. It is known that one of the popular authors of science wonder stories is an assistant professor of chemistry in an eastern university. Another frequent contributor is the proprietor of a speakeasy on Park Avenue, who does not need the money but writes for the joy of it. He takes great pride in the immaculate condition of his manuscript and offers a box of candy to any sub-editor who finds an error in it. The truly professional Pulp author (often a former newspaper man) earns his living at it by grinding out from one thousand to five thousand words a day with grim regularity. Energetic writers who have caught the fancy of the Pulp public have been known to make $25,000 a year.

In the popular fiction of blood and action the native American finds his happier and far more heroic double

Since they are paid by the word, the prosperity of professional authors depends upon their speed; hence they have developed what is probably the fastest rate of literary creation in history. One favorite writer produces his stories so swiftly that the sub-editors dread having to handle them because the manuscript is so extraordinarily had. The trouble is, he doesn't take time to read over what he has written; he is likely to get well into a sentence, forget how it started, and leave it dangling in mid-air without a verb or a predicate. The editors can tell when he interrupts a story to go to lunch because when he resumes the story he frequently has forgotten which character is which and is likely to get the hero and the villain mixed up.

This is a common mishap with Pulp writers; so common that a precautionary method has been devised by one veteran. Before starting to write a story he takes a clean sheet of paper and notes on it, for instance. "Hero: Fred Smith: red hair; brown eyes; six feet: twenty-two." Each time he introduces a new character he makes similar notes. This system, he says, practically guarantees one against the danger of referring to the villain as a short, stocky man with a gold tooth on page nine and as a tall, hawkfaced individual with porcelain uppers on page eighteen.

a Numerous such tricks of the trade make life easier for the experienced Pulp writers, and they exchange their knowledge with a true fraternal spirit. A Kentuckian whose onlv nautical experience has been a ten-day wedding trip on the Great Lakes ma\ decide to do some sea stories. Does lie thereupon waste time going around the world on a freighter to get atmosphere? By no means, lie writes to a confrere in New York who has published sea stories asking for a glossary of terms and a few salt-water superstitions. In return, he sends a corresponding data sheet on horseracing so that the New York sea-story author, who may never have seen a race outside the newsreels, can make his next hero a jockey.

There is, in fact, a trade journal for Pulp authors which makes a business of supplying atmosphere. Special articles cover stage terminology, description and native phrases of Hawaii, prison patter and the language id' loggers. Plot advice also is given. One seasoned fictioneer confided to his fellow Pulp authors that he had for years drawn his plots out of anecdotes in the Bible which he had put into modern dress and sold to every sex magazine printed in English.

The mass production of day-dreams by the Pulps has been accompanied by a phenomenon unique in literature: the standardization of fiction. Even as Fords and hairpins are standardized, so are stories. These magazines represent the incursion of the Machine Age into the art of tale-telling.

By the process of trial and error through the careers of the Pulps, definite specifications have been evolved for the various types of stories. The specifications have been formulated into a series of editorial rules, both commands and taboos, which assure the essential sameness of all the stories. Should the authors slip up, it falls to the sub-editors to enforce the taboos by revising the manuscripts.

Here is an actual incident showing how it works. A Western story magazine hungered for "romantic adventure of the glamorous West; love is paramount but stories must he packed with cow action." A story was submitted which was brimming with cow action, was just what the magazine wanted—except that the hero, after passing through a splendid assortment of perils, was rescued in the end by three airplanes. Now, airplanes were strictly taboo in the magazine, so a sub-editor was instructed to eliminate them. He did; he changed "whirring" to "thudding," and "gleaming wings" to "foam-flecked haunches." The three airplanes became six horses and the story went to the printer.

Continued on page 51

Continued from page 27

The reason for the standardization is not to help speed the mass production —although it does enable the Pulp writers to turn out the reams of stories they do—but rather to make the yarns conform with the pattern of their readers' natural day-dreams. The Pulp customers never allow social problems to intrude into their own flights of fancy; hence the magazines rigorously bar any touch of contemporary realism. Heroines never are concerned about careers, only about wedding rings; war is never disagreeable, but always a glorious adventure; and there is no Depression.

Mr. Hoover's Committee on Recent Social Trends solemnly thumbed over a lot of Pulps looking for "attitude indicators" which would reveal approval or disapproval of such matters as old-fashioned religion and morality. The Committee noted that the Ptdps were very conservative. Two hundred and thirty-three attitude indicators showed disapproval of sex relations out of wedlock, immodesty and the like, while only thirty-one attitude indicators showed approval of such laxity. This gave a twelve percent approval as compared to a thirty-five percent approval of indiscretion in the quality magazines. The Pulps also were unflagging in their enthusiasm for family life and the rearing of children, whereas the quality magazines betrayed a sharp falling off in the desire to produce offspring. In sum, the Pulps were the most moral of any magazines.

Mr. Hoover's Committee appeared a bit surprised at this conclusion. Rut it needn't have been, because the Pulps know what they are about. They have found that the philosophy of their readers is a synthesis of Sunday School lessons. Therefore it is by rigid editorial specification that the magazines are highly moral, so that nobody will be shocked.

The remarkable standardization extends even to the characters in the stories. The reader puts himself in the most desirable role, and some enemy in the least desirable; so the heroes are all good and the villains all black, and that's all there is to it. The characters need have no more individuality than so many dummies in a tailor shop.

Consider, for instance, the heroine in magazines like Sweetheart Stories or Thrilling Love. No matter how many different names she may bear, she is still the same pure girl in every story in every issue. She must:

Be young—between 18 and 24.

Radiate physical loveliness.

Work for her living, earning barely enough to get by.

Be as pure in thought as in deed.

Win her man in lawful wedlock in the end.

She must not:

Defile her lips with nicotine.

Have a college education.

Touch strong drink.

Display any sense of humor.

Allow kisses by any hut parents or fiancd.

And when the same throbbing climax comes in every story, our little heroine invariably is found panting in a genteel manner. "He had called her sweetheart—at last," recounts Thrilling Love. "Her lips parted a little, her breathing grew a bit more rapid. He was regarding her with a rapt, earnest expression; and as he lifted his hands to her elbows, she swayed slightly toward him."

The heroine of magazines like True Confessions is, on the other hand, a scorched butterfly who has seen plenty of sin in her time. But her soul must he seared in accordance with an invariable pattern! She may violate virtually all the commandments save those laid down by the Pulps. The result is that a genuine confession seldom is acceptable. A girl serving time in a Middle Western prison once sent in the unsparingly truthful account of her seven years' career playing the badger game. For biting characterization, for analysis of emotion, her story was far better than anything the editor had received. The story, however, was rejected, ft was too real; it did not conform to editorial specifications. She had not told how she had been an innocent young girl filling her apron with cowslips on grandfather's farm when a sinister stranger lured her to the city with promises of a diamond tiara. Nor, still more important, had she writhed through her past to the moment when she realized in a blinding flash that she was purified by the love of a good man who forgave all.

The heroes, equally stereotyped, must be as handsome as a collar ad, as virile as Jack Holt, and as clean as a boy scout. Take, for instance, Robert Wallidge in a story called "Second Best": "Tall, good-looking, and teeming with vitality, he was about as popular as any one man had a right to he. Blessed with an amazing fund of energy, he commanded an income rather out of keeping with his youth, as an attorney. He was a sportsman to his toes."

In the magazines that have to do with the World War, of which there are a couple of dozen, special pains are taken to make the hero impervious to fear. The verb "cry" is officially banned even as a synonym for "say". A phrase such as " 'Put that down', he cried", is altered, lest the readers misunderstand, to " 'Put that down,' he gritted". The hero may also rasp, grate, husk, rip or jerk whatever he has to say, so long as he never cries it.

Hairy-chested as they are, these Pulp he-men are alike in their careful avoidance of strong language. Heroes in the trenches can, under the stress of excitement, exclaim "cripes!", but must not let slip either gee or geez, which are forbidden as blasphemous. The oldest of the Western story magazines has never had its pages sullied by a Damn.

Continued on page 60

Continued from page 51

One must not be too supercilious about the Pulps. The New York Public Library, no doubt after grave consideration, has found them worthy. It buys them all. They are withheld from the casual readers, because the Library feels that its periodical room should be occupied by persons of somewhat better literary tastes. It fears, perhaps with reason, that if the Pulps were made available generally there would be no seats left for people who wanted to read, say, The Literary Digest. But, though hidden, the Pulps are there, and anyone with a serious purpose may have access to them. Solely out of a sense of duty to the coming generation, the Library solemnly binds and stores away the Pulps in the belief that they contain valuable sidelights on the social history of the twentieth century. Future scholars may wish to study these embalmed day-dreams to find out how the American proletariat reacted to the Machine Age.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now