Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowNew York: the municipal mess

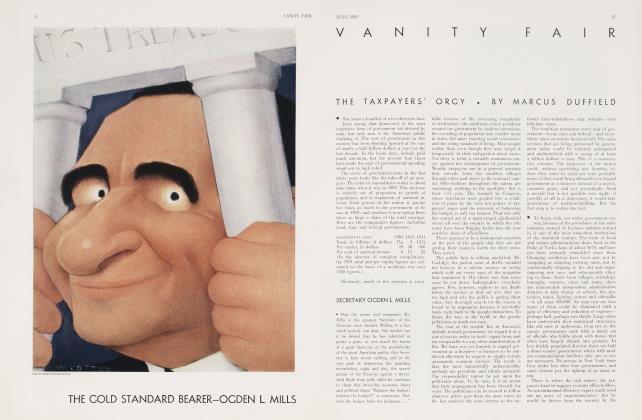

MARCUS DUFFIELD

A story of the devious and preposterous ways in which taxpayers' money is thrown into the community sewer

The chief reason why Tammany Hall whisked Joseph V. McKee out of the mayor's office in such haste is, of course, that McKee threatened to put New York City on a business basis. This struck terror into Tammany hearts. The Braves shivered at the prospect of having to let city contracts to the lowest bidder: what would become of the gravy? The idea of eliminating thousands of unnecessary city employees was horrifying: how could the organization take care of the boys? Moreover, the present 150,000 city employees are all necessary from Tammany's point of view; figuring that they can bring in four votes each, the total is 600.000 votes, which is needed to make sure of winning elections. Naturally the Tiger had to shelve Mr. McKee as quickly as possible as a matter of selfpreservation.

His sober interregnum, however, is an illuminating episode not only in the history of New York's city government, but for municipal government throughout the country. With rare exceptions, the attitude has been that the conduct of civic affairs is a mysterious process to he carried on with little regard for business methods. Mr. McKee has indicated the possibility that a city can be run on exactly the same principles as any other large corporation. He has not been allowed to do more than make a hare beginning. But he has given the taxpayers an inkling of the millions they throw away every year; and it is yet possible that the citizenry will have caught the idea that they are paying about SI 16 for every $100 worth of services obtained from their civic corporation. It is now generally agreed that New Yorkers could save themselves one hundred million dollars a year without the slightest impairment of the services they receive simply by insisting that their government be put on a basis of efficiency.

Citizens of other municipalities throughout the country need not laugh at the folly of New Yorkers; nearly all the municipal taxpayers are allowing themselves to be mulcted in just the same fashion. A few glances at the avenues of civic common sense which McKee has opened up will be just as instructive for the citizens of Los Angeles and St. Louis and Detroit as for Gothamites.

When he replaced the gay Jimmy Walker as New York's mayor, the grave McKee caused a general gasp by arriving at City Hall in the subway, instead of rolling up. as did his predecessor, in an exceedingly expensive motor car bought and maintained by the city. This use of the subway was unorthodox and unprecedented. City dignitaries are accustomed to traveling to their offices in limousines, except, of course, when their wives have taken the car up to the Catskills or their daughters have gone out for a spin on Long Island. These motor cars are owned by the city and kept up by the city and chauffeured by employees of the city. Not counting the police and fire department automobiles, there are something like 849 pleasure cars for politicians and their wives and daughters to ride around in at the expense of the taxpayers. Commissioners have them, and deputy commissioners, and the deputy commissioners' secretaries. The executive staff of the Borough President of Brooklyn consists of 63 persons, of whom 23 are chauffeurs. They are not cheap cars that New York City's officials sport; there are 71 Cadillacs, 12 Lincolns, 24 Packards, 10 Pierce Arrows, and two Locomobiles.

Realizing that even the biggest private firms are not given to bestowing pleasure cars on their employees, Mr. McKee moved to end the limousine racket by ordering out of service the fancier part of the motor fleet, and thereby hoped to save $600,000 a year. An even greater sum—at least a million dollars a year—could be saved if New York made a clean sweep of its superfluous automobiles by following Boston's example. Boston, beset by budget troubles, sold all its officials' cars and ordered them to hire driveyourself taxis by the hour when necessary.

Elimination of the limousines would, of course, throw dozing chauffeurs out of work. They would not be the only city employees to lose their jobs if the municipality were to be put on a business basis. The city is over-staffed probably as much as 20 percent. McKee, understanding. the situation, began to trim the personnel by refusing to fill vacancies except in cases of absolute necessity. Certainly this was handling the problem with gloves. Much more drastic methods are called for, in view of the fact that thousands of city employees are workers only in name—actually they are recipients of a community dole dispensed not generally but to office-holders' friends and political henchmen.

There are, for example, 231 bridge tenders on the payroll. Bridges that have not yet been opened, bridges that have long since fallen into disuse have their tenders, sometimes several to a span. Some tenders rarely visit their bridges. By the same token, there are inspectors who have nothing to inspect, supervisors who have no men to supervise. Sanford E. Stanton, who made a study of the subject of city waste, reports the following oddities, among others, in the personnel situation:

In the Bureau of Records, four overseers watching over 20 clerks, whereas one overseer should he able to guide 200 or more clerks.

Secretaries unfamiliar with shorthand and typing who therefore have to have their own stenographers.

The spreading of $5 worth of paint by $95 worth of workmen; the use of six million dollars' worth of labor on a job requiring $35,000 worth of materials.

Nine bosses bossing 14 employees in the Ward's Island sewage plant.

The successful conduct of the Sanitation Department on one occasion despite the officially reported absence, for one reason or another, of 4,000 of its employees.

Swarming over New York City are 1.152 inspectors, many of whom without doubt are performing useful services conscientiously. But they are far too numerous. They descend in hordes upon a skyscraper in construction: inspectors of plumbing, electricity, fire escapes, cooking systems, oil burners; inspectors from the Bureau of Buildings, from the Tenement House Department, from the Bureau of Fire Prevention of the Fire Department, from the Department of Health. They get to he a pest, causing confusion and delay. Scores of inspectors could be eliminated to the relief of everybody if the inspectorial system were concentrated in one unit.

With so many inspectors at large it is small wonder they get careless at times. An investigator for the Mayor once checked up on the work of the Bureau of Weights and Measures inspectors and found 1,382 irregularities in 1,347 cases checked. Among the places whose scales had been approved were 10 vacant stores, 3 vacant lots, 14 shops that could not be found, and a gospel mission. The harassed Commissioner of Weights and Measures explained that his assistant who supervised the inspectors had been absent on sick leave for five years. She had drawn her pay all the time, of course, and in fact had been given an increase. Why had she remained on the payroll? "She was," the Commissioner testified, "a strong-willed woman."

That particular Commissioner was roundly denounced by the mayor's investigator in 1930 as unqualified to hold office. He is still in office and his salary has been increased from $8,000 a year to S9,000.

The superfluous small-salaried employees would by no means be the only victims of an efficiency regime. There are 90 Democratic district leaders and their relatives, together with 16 Republican district leaders, on the city payroll drawing a total of $715,000 a year. Those jobs were granted without civil service examinations fundoubtedly a fortunate circumstance for the appointees) and at least half of them could be wiped out without any loss to the effectiveness of the public service. Bureau heads who are accustomed to spending the winter in Florida, deputy commissioners who are in the habit of dividing their time between Saratoga, Bowie, and other tracks; and doctors, lawyers and engineers on the payroll who seldom approach City Hall because of the demands of their private practices— all such supernumeraries would be dispensed with, just as they would be in a business corporation.

(Continued on page 62)

(Continued from page 54)

The principle on which the city has apparently been acting in hiring personnel has been that no one man should perform a job which two, three or even four could do; which is not precisely businesslike. The largest element in the current budget is the cost of personal service, approximating $368,000,000, or nearly half the total. This has been going up at an astonishing rate. It more than doubled between 1918 and 1927, and has increased another eighty million dollars since 1927; in the last five years 32,380 new jobs have been created. By dropping perhaps a few thousand workers who do little or no work. New York City could save millions annually.

The principle on which the city buys apparently is that no article should be bought for S3 which could be obtained for $7.50. Within a few days of taking office, McKee saved the city S50.000 by having election ballots printed by the lowest bidder for the job instead of by the highest bidder, who had enjoyed the bulk of the city's printing business for years. Often there is no competitive bidding at all, because the Board of Aldermen exercises its power of permitting "emergency" purchases. Such "emergencies" pop up nearly every time the Board meets. Recently some functionary was enabled to leap into a breach with purchases of furniture for the new Bronx County Courthouse. He bought 12 judges' chairs at $115 a chair; 12 clerks' chairs $43; 900 chairs for the public 6a $12; 24 wastebaskets @ $12; and 100 cuspidors @ $3.

Mr. McKee apparently bad the idea, strange to most city administrations, that the business enterprises in which the city is engaged ought to be selfsupporting, at least, or else abandoned. He selected as a point of attack a terminal food market in The Bronx which the city operates for wholesalers. The market cost about 19 million dollars in the first place, and its operation eats up some $162,000 a year, of which $148,000 goes to pay the 70 or more employees. But the market has just four tenants, who pay some S20.000 a year. That leaves a deficit of about $140,000 a year which the taxpayers have to dig from their pockets. McKee noted that in the engine room one out of the 13 engines were running—under the supervision of several foremen, eight laborers and 36 helpers. Most of this crew apparently was in the habit of turning up for work only on pay day. McKee dismissed the commissioner responsible, and ordered the market closed. Tammany later restored the appropriation for the market in the budget.

Fantastic as is this instance of waste in the Bronx Market, it is by no means a unique example of New York's disregard of the simple business principle that departments and enterprises should be self-supporting. McKee might have gone much farther along this line. There is a Bureau for the Collection of Arrears in Fersonal Taxes which costs $50,000 a year to operate. It collects $20,000 a year. There is a seven-million-dollar municipal airport in Brooklyn which is supposed to pay its way through the leasing of hangars to private airplane companies, but it loses about $100,000 a year.

The city ferries plying in the harbor are supposed to pay their way, but they do not. The Commissioner in charge proposed to abandon the ferry from Twenty-third Street to Greenpoint because it was such a consistent loser, but the Alderman from Greenpoint pleaded with the Mayor, who was at that time Walker. "Don't take away the old ferry," he said. "There would be tears in the eyes of those ferryboats, as there would be in the eyes of the people of Greenpoint. T hey ask you. those ferries do, to love them in May as you did in December." The Mayor was reported to have been visibly moved, and the ferry plies on, eating the taxpayers' money to keep Greenpoint's eyes dry.

This ferryboat incident also illustrates another obstacle in the path of anyone trying to put New York City on a business basis—an obstacle perhaps even greater than the impregnable greed of Tammany Hall. The citizenry as a whole wants the budget cut—but the citizenry is made up of a myriad of little groups, each with a pet project. If any of the pet projects are tampered with in the process of cutting the budget, a fearful howl arises. Add the various howls together and the upshot is that the very taxpayers clamoring for economy are, in their capacity as members of small groups, blocking it.

Moreover, the populace insists upon keeping its finger in the governmental pie. This necessitates the retention of a maze of clumsy machinery providing for popular representation and for local autonomy which has long outlived its usefulness and should be scrapped. The structure of government in New York City, as in many other cities is admirably adapted to foster waste and, in fact, almost precludes the possibility of efficiency. Overhauling it would be simple enough if the people could be induced to cast off old governmental habits. Until they do, neither McKee nor anybody else can bring about further elimination of sheer waste totaling further tens of millions of dollars.

(Continued on page 69)

(Continued from page 62)

New York County is identical in its boundaries with Manhattan, the affairs of which are conducted by the mayor and the city government. But because counties were important units in England in the days of the early Georges, modern Manhattan has a complete county government; so does Kings County, which is Brooklyn, and Richmond County, which is Staten Island, and so on. The county officials have virtually nothing to do except draw their pay, and they and their offices and their assistants and secretaries and stenographers and motor cars and chauffeurs are maintained by the taxpayers. The chamberlain long ago was an important member of the household of the English kings; so New York has one. 11 is sole duty is to take city revenues over to the bank and deposit them, which is not enough work for a grown man. The city once had a business man for a chamberlain and he resigned on the ground there was nothing for him to do. The subsequent chamberlains have been content to draw their salaries.

In mediaeval England the shire reeve was a busy official who, bearing a halberd, kept the peace and acted as hangman when necessary; so now New York has a sheriff, who does not bear a halberd and is superseded as hangman by the electric chair in Sing Sing. If he notes a disturbance of the peace, he calls a city policeman. He has a staff of 122 to help him do practically nothing. The sole contribution of the sheriff to modern life in recent years has been to make the tin box famous.

There is no conceivable need of having court houses strewn through five counties. One or two courthouses in Manhattan might be more convenient for everybody concerned, and far less expensive. But the various local chambers of commerce insist on having a handsome court house apiece, presumably to point out to visitors. Each of the many courts has its own set of subordinate officials who, among other things, register titles and deeds which would be much more accessible if registered economically in one central office.

In addition to the county governments, there are the borough governments, instituted as recently as 1898 when Queens and Staten Island were remote country suburbs afraid of being abused by the wicked city of New York. To preserve their rights they and the other boroughs insisted on having autonomy. So each has its own president and its own governmental structure which has been almost wholly superseded in fact if not in theory by the municipal regime of greater New York City. When the borough governments were instituted it was feared that the borough presidents would have too little to do and not enough patronage to dispose of, so certain city functions were split up among them, notably the privilege of building sewers. This has been a source of great profit to borough politicians and considerable grief to the taxpayers. Apart from the matter of graft, the sanitation work could be much less expensively and much more efficiently done if one trained city official were in charge throughout.

Of all the ludicrous and expensive vestigial units of government, the Board of Aldermen is undoubtedly the champion. In times forgotten it was felt that no government could be complete without an upper and a lower legislative chamber. So New York provides itself, according to the current fashion, with a Board of Estimate (Senate) and a Board of Aldermen (House of Representatives). In the course of years the duties of the Board of Aldermen have been pared away by the legislature, by charter amendments, and by reason of the obvious uselessness of the Board itself. Yet the dear old Board of Aldermen still meets once every Tuesday (except during the summer), for as long as 20 minutes a time on occasion. There are 65 Aldermen, who draw $5,000 a year each for their arduous duties, except the lone Republican who as minority leader gets $7,500 (he has a secretary at $3,000 and a messenger at $2,000) and except the assistant to the presiding officer who also gets $7,500, and except the president, who gets $10,000 a year. The Board, unable to rely on the city police to keep out the crowd of citizens at its doors (sometimes as many as two persons), has a sergeant-at-arms and ten assistant sergeants-at-arms, or almost enough guardians to look after the 435 Representatives in Congress. These ten assistant sergeants-at-arms seldom get to meetings and are not missed.

The substantial and permanent reduction of New York City's budget is not a matter of a few spectacular moves, but a matter of effecting hundreds of small economies—the sort of economies which would have been instituted long since by an efficiency expert in any other large corporation so near financial chaos as is New York today. In taking a few preliminary steps, Mr. McKee indicated some of the important lines of endeavor: abolishing luxuries, removing superfluous personnel, putting city enterprises on a paying basis, centralizing purchases on a scientific instead of a graft system. He was thwarted before he got well started by the office-holding ring jealous of its jobs and its booty. Mr. McKee could not even attempt the more important economies which would be brought about by pruning away the great mass of dead wood in New York's governmental structure. The groaning taxpayers themselves would have defeated him in that.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now