Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowI know it does little good to find fault with the way this universe of ours is run. But it does seem a pity to me that we cannot live to be a hundred. It would give us a chance to judge the affairs of men from a more or less balanced point of view, whereas now we are obliged to get our perspective by proxy.

We are forever bothered by the conviction that the time at our disposal is much too short, that we have not been able to gather enough data upon which to base any sort of a general law in connection with mere human existence, and that we shall have to depart for our unknown destination about as wise as when we first delighted our parents with a feeble cry for food and comfort.

I suppose that that is one of the reasons why the human race struggles so tenaciously to hold on to its fairy stories. Without those charming fables it could never muster up sufficient courage to go on with the show.

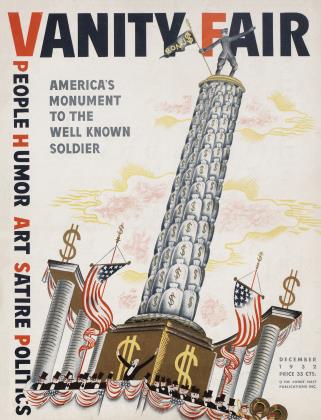

I realize that I am writing this in the middle of the great Era of Science which was to set all of us free, with its myriad miracles and its glorious conquest of time and space and energy. I also realize that the further we penetrate into that region of the Truth as Revealed according to the Tables of Multiplication, the more hopeless the general outlook upon life, the more widespread the feeling of despair and lassitude which is rapidly overtaking vast multitudes of our contemporaries. Indeed, when I hear all the smart wise-cracks of my neighbors about "what this world needs is a good five-cent nickel" or "a good five-cent congressman," I feel more and more inclined to answer, "What this world needs is a good, soul-satisfying Fairy Story."

One thing these fifty years among the human race have taught me is this: that man can live without bread and without butter and without jam, but that he cannot live without his fairy stories. If you want further proof of this, look at the funny little red-garbed derelicts who stand at the corners of our streets and ask you for "alms for the sake of mercy" during the present Yuletide season. Officially they are the accredited representatives of diverse charitable organizations. Unofficially they are the living proof of what I have just said. They are the relics of an old, a very old Fairy Story. They are the direct descendants of one of the oldest Fairy Stories connected with our own species of the so-called Indo-European race. They have survived empires and kingdoms and they ante-date the Papacy by several thousand years. They jingle little bells for fifty cents a day, and at night retire to some obscure lodging-house, the poorest among the poor, victims of the great and beneficent age of science. But they are first cousins to the mightiest of all Germanic gods and to one of the best beloved among the ancient saints. As such we should respect them and give them a little more than we intended to do.

I first met the good old Bishop of Myra when I was about four years old, on the fifth of December. He had visited me regularly once a year ever since I was born, but when I was four, I saw him face to face. He rode over the roof of our house and I heard the clattering of the horse's hoofs. Also in the morning the straw which I had placed in my shoes in front of the open fire was gone. The good Saint had sent his black man Friday down the chimney to get that straw. And in return for my kindness (one good deed deserves another) he had left me those presents which, duly enumerated, had been mentioned to him in a letter addressed to his somewhat vague whereabouts in the Kingdom of Spain.

Reader, tell me not that all this was not true for I would refuse to believe you. It is a long time since I watched the wintry sky of my native village in Holland to get a glimpse of the white-bearded old gentleman as he leisurely trotted across the roofs of the neighbors' houses. Now the fifth of December here in the land of my adoption means nothing but just another day. Nevertheless when the fifth of December comes, so does the Saint. I may be the only man in New York to see and hear him. But I know that he is there. He no longer brings me any presents; but how can I fill my shoes with hay in this city, and how can I leave both shoes and hay in front of an open fire-place in a Manhattan Hat?

Once, a very short time after the war, I was having my shoes shined by an amiable old Italian, and I said that it was nice that the war was over and now there would not be any more fighting, for Germany was beaten and we could breathe freely once more. But the old Italian shook his head and said no, and he told me that I did not know what I was talking about, for although Germany was beaten she was not really beaten, for she had put four billion dollars in gold on an island somewhere in the North Sea, and that island went to the bottom of the ocean whenever anybody came near it, and it was guarded day and night by an old man with a white moustache and when nobody was paying any attention, that island would come to the surface and the Germans would take their four billion in gold and conquer the world.

Could anything have been more marvelous than this jumble of history, fairy stories and just plain nonsense? Try and figure out for yourself what queer and hazy and half-forgotten and badly remembered recollections lay huddled together in the brain of that old boot-black man. The Kyffhauser Mountain of Frederick Barbarossa had been changed into Heligoland. Barbarossa himself had assumed the shape of Bismarck. The tower of the fortress of Spandau where the golden millions of the French indemnity of 1871 had rested for such a long time had become the countless billions of which the Allies were then talking. But most mysterious of all, the old island of Saint Brandan off the African coast, the horror of all mediaeval mariners because it had the uncanny habit of slipping towards the bottom of the ocean whenever a ship came near, had got itself so hopelessly involved with Heligoland and the Kyffhauser that the three had become one and that only an experienced folk-lorist could detect their highly different origins.

"But this fellow," you may well argue, "was just an exception. Perhaps he read fairy stories and history in his hours of leisure. Perhaps he was not very bright." I knew him rather well. He was of average intelligence and never read anything except his own Italian paper. But sagas are like weeds. They will flourish even under the most uncomfortable of circumstances—as I hope to prove to you now, by submitting our little red Santa Clauses to a short examination.

That Wotan, the mightiest of the ancient Teutonic Gods, should have survived the onslaughts of Christianity is nothing out of the ordinary. The greater number of the old Gods survived in one way or another, as any historian will tell you. That I was really looking for Wotan when I was trying to catch a glimpse of Saint Nicholas is such a self-evident fact that it needs no elaboration. The long bearded Valhallian with his white horse had merely donned Christian garb, as Christ himself had adopted the halo of the Sun-God Apollo before he could begin his triumphant march through the Hellenistic world.

It has been said, and truthfully, methinks, that no race can ever be entirely defeated on its own soil, and the same holds true of gods and Fairy Stories. No power is sufficiently strong to eradicate them unless it kills absolutely every man, woman and child who was ever exposed to the nursery-tale. Even then there have been cases where the fable proved mightier than the sword. Our own Santa Claus is proof of this.

First, a few words about the original Saint Nicholas of history. Historically speaking, he is as vague a figure as Zeus or Minerva. Both the Romans and the Greeks of the early Middle Ages worshipped him as a former Bishop of Myra in Asia Minor. When that Bishop had lived was highly problematic. The date of his birth was the sixth of December and it was said that he had been present at the Council of Nicea which was held in 325. This therefore allows us to guess that the good Saint (if he had really existed) must have been born sometime during the second half of the third century.

But this, of course, interested nobody. Chronology was an unknown science among the earliest Christians. They gave the date of the birth of Christ four years too late, and spent four centuries debating whether he was born on the twenty-fifth of December or on the twentieth of April, the twentieth of May, the twenty-eighth of March, or the sixth of January. The struggle between the adherents of the twenty-fifth of December, and those who clung to the sixth of January (the same day as that on which the marriage in Cana took place) gave rise to severe and bloody conflicts which lasted for several generations, until in the end—chiefly under the influence of the newly converted inhabitants of northern Europe, who celebrated the twenty-fifth of December as their own new year— that date was selected as the "official" birthday of the Christ.

This, merely in passing. The point I wish to make is that the vast majority of the people are little affected by what we are pleased to call "scientific historical evidence." They loved the good old Bishop of Myra and intended to go on loving him, and they were willing to slaughter all those who doubted the authentic details of his unauthentic life, and that was all there was to it.

But even these authentic details were meagre. On all the old pictures of the good Saint we see him with three small boys. Those three children had been rich boys, murdered by a rapacious hotel-keeper, cut up into pieces and hidden in barrels of brine, but brought back to life by the Saint who had known all the time what this inn-keeper was up to. Other pictures show him with three girls. They were the daughters of a poor Lycian peasant who was unable to provide them with dowries and therefore intended to make them business associates of Mrs. Warren, nee Shaw. But the Saint had secretly provided them with three purses filled with golden doubloons, and they had been saved from a fate that was worse than a fate that was worse than that, for which reason it became a good and holy fashion to send your friends mysterious packages on the birthday of the Saint, on the sixth of December, and never thereafter reveal that you were the generous donor.

And now this is what interests me most. With the coming of the Reformation, all the saints were banished from the Low Countries along the banks of the North Sea; but this one particular saint could not be budged. All the edicts of the Synods and the Estates of the Dutch Republic of the sixteenth century were of no more avail than the act of Parliament of 1644 which forbade the celebration of Christmas, calling it a survival of the days of heathenish ignorance. The reason was plain enough. By that time the Lycian Bishop had become so completely identified with Wotan that he had become part and parcel of the natural landscape of the great North European Plain. He looked like Wotan, he dressed like Wotan, he behaved like Wotan. Except that he was infinitely more generous and in the most agreeable of all possible ways he was generous without making a fuss about it, for to give some one a present on the day of Saint Nicholas without strictly hiding the identity of the donor was quite as much against the strict etiquette of the occasion as it would be to send a lady a flower for Christmas without attaching a card.

Another strange detail: Saint Nicholas was no longer a native of Asia Minor, but he lived "somewhere in Spain." I suppose that during the eight years' struggle for liberty, when everything Catholic was spoken of as something "Spanish", the old gentleman also changed his address. But he did not care, and he remained as vigorous as ever. Nor does he seem to have worried greatly when his birthday was transferred from the sixth of December to the fifth. That was the result of ordinary, everyday snobbishness. The common people celebrated St. Nicholas during the daytime of the sixth. So the rich began to hold their celebrations on the eve before the sixth. And then the poor followed their example and the sixth of December became the day after Saint Nicholas, when little children are apt to go through the same physiological agonies which they suffer in our own fair land on the day after Thanksgiving.

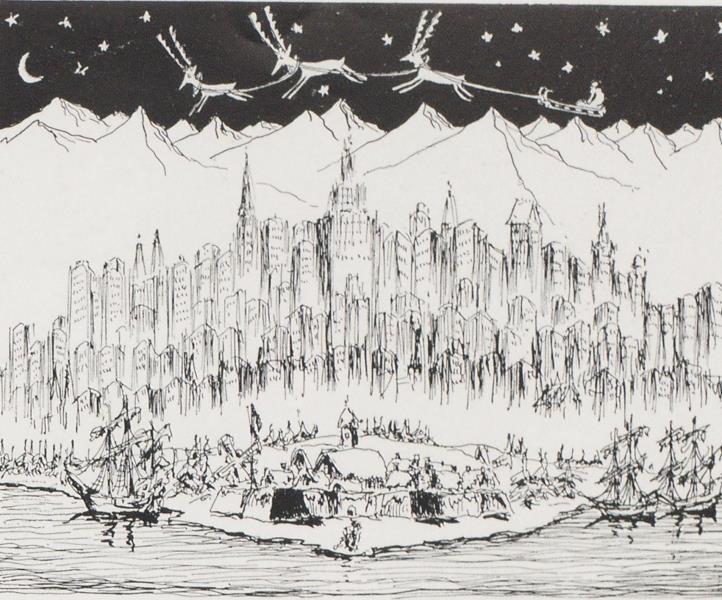

The Dutch who settled down in Nieuw Amsterdam and lived here for two generations brought their queer composite Saint with them and celebrated his birthday in the usual fashion and on the usual day. And as he had no competition to fear from the North and very little from the South (the Puritans celebrated Christmas as a sort of private Yom Kippur, with a day's fasting), he prospered until the vast influx of latter-day English brought their Yuletide and the other remnants of the feast of those "ancient Angles" which had so greatly shocked the earliest missionaries who had preached the Gospels to the barbarians dwelling in those distant isles.

Then came the immigration of the Germans, who during the latter half of the eighteenth century had begun to celebrate Christmas with a fully lighted Christmas-tree at the base of which the customary presents of Saint Nicholas Day were heaped together, still in a slight guise of incognito. Then came the Italians, who had never known Christmas as a day of family life, who recognized no Saint Nicholas and no Wotan, but regarded it merely as another church festival when—according to a pleasant habit instituted by the good Saint Francis—the Church showed the birth of Christ in a small replica of stone or putty and brightly colored palms and cows.

And out of this mixtum-compositum of several nationalities, one German deity, one Mediaeval saint, half a dozen legends, a couple of Fairy Stories and a well-known poem, The Night before Christmas, and the irrepressible desire of mankind to give something to some one just for the fun of giving, we have gotten our own modern Santa Claus and our own Christmas.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now