Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

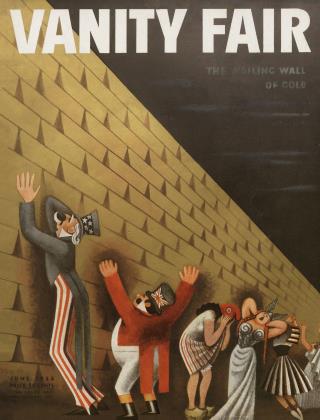

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWill the Kaisers return?

RICHARD VON KÜHLMANN

Harshly, the telephone rings through the halls of one of those few Berlin private houses which, despite all the distress of the dav. still maintains a shadow of that city's famous hospitality.

"This is the Palace of the Netherlands, sir. Her Majesty requests your company on Wednesday at one o'clock for breakfast."

"I shall obey Her Majesty's command with pleasure. How long does Her Majesty intend to remain in Berlin?"

"A stay of ten days is intended." answers the melodious voice of the trained courtier. "1 am certain," he continues, "that Her Majesty would take great pleasure in dining at your house and meeting several interesting people in the political, literary, or social world."

"I would regard this as a high honour, and I request Her Majesty simply to name the day and the hour. I shall keep in touch with you in respect to the persons to he invited.

That morning, the newspapers of the Right had announced: "Personal Notices: Her Majesty, Empress Hermine, coming from Doom, has arrived for a short stay in Berlin at the Palace of the Netherlands."

This palace—a small and dignified building in the Unter den Linden—was left to the Hohenzollerns at the time the German Republic was founded. It is used by the Empress as a regular residence on her frequent trips to the German capital. Her husband, of course, always stays behind in exile. But with his family establishing closer relations in the home country, and with the arrival of a nationalist restoration in government—what may be the outcome?

"Will Hitler bring the Emperor back to Germany?" That is the question which is asked of a German everywhere in America. According to trustworthy private reports. Chancellor Hitler recently expressed, in conversation with the Empress, his belief that the time was not ripe for a monarchy. In his speech at the opening of the new Reichstag in March of this year, he stated that the question of the monarchy was not a matter for discussion at this moment. This confirms the opinion of many who believed from the beginning that Hitler would not add to the complexity of a task that is already difficult enough, by bringing in the royalist problem. But the problem will continue to busy the minds of Germany and of the outside world. It is worth our while, therefore, to draw the portraits of those persons of the House of Hohenzollern who may be considered as possible German Emperors and Kings of Prussia.

To begin with, the House of Hohenzollern is the only dynasty that is available for the German throne. The rival House of Wittelsbach, which ruled Bavaria for centuries and has strong support today, is practically ruled out by reason of its allegiance to the Catholic Church. If such a minority rule were instituted, Protestant Prussia would protest indeed.

"I.R."—these two letters, the initials of the Kaiser's former title Imperator et Rex, still appear under the signature of the exile in Doom. Wilhelm II. as head of the House of Hohenzollern. is the first name that comes up when the revival of the crown is mentioned. He has changed greatly in exile; and if the sparkling vitality of his conversation calls up an illusion, it is still true that the profoundly difficult years of his estrangement just before and during the War have left deep marks upon him. The white hair and white pointed beard have brought out more clearly his resemblance to his brother, the late Prince Henry, to his cousin, the murdered Czar of Russia, and to his other cousin, King George of England. Even at the time of his coronation. many people commented on his sickliness and prophesied a brief reign; and today, at seventy-five, he is certainly no young man any more.

But so far as one can learn from occasional conversations, the Emperor has retained his composure in the loneliness of his Dutch exile. His able mind is no adequate or reliable balance against a fundamentally soft and kindly heart, and an easily aroused, far-flying imagination. Even now, in his days of grey-beardedness, he retains much of what is youthful; and if he happened again to be German Kaiser, in his Bellevue Palace in Berlin. he would give the same impression of impulsiveness as in the old days. The weight of a life that has been deeply tragic, even if borne with dignity, has noticeably deepened the religious side of his character. This religious side had begun to reveal itself in the terrible years of the war; and without it. a great many things—especially the decision to flee to Holland at the time wdien everything in Germany collapsed—would barely he comprehensible.

Continued on page 55

Continued from page 22

Now and then, the Emperor speaks of his hope and firm belief of being restored as ruler of the German people. Mow far he really believes in this idea is difficult to surmise, and could be fathomed only if one were able to penetrate more deeply into this complicated and strangely divided personality. In former days, Wilhelm II was faced with the immensely arduous task of creating the type of a modern German Emperor. One can say that now he has created the type of a monarch who lives in exile with dignity and gentility, after having suffered heavy reverses of fortune.

His second wife, Empress Hermine, is one of those people who show up notoriously poorly on photographs: her pictures are like caricatures. Not that one could describe her as any beauty in the classical sense; but she knows how to captivate those who meet her. A versatile mentality and a certain natural warmth brighten her features. Of course, the charm of her conversation does not exclude cleverness and diplomatic calculation.

At the time she married the Emperor, she decided, with much wisdom and political realism, on frequent absences from Doom. She associates in the society of German intellectuals, financiers, and statesmen. Of all the influences which claim to be working for the return of Wilhelm II to the German throne, Empress Hermine is certainly the most honest, the most modern, and the most adroit.

The Crown Prince—a different type of man from his father—does not share the exile in Doom. When he and his wife have not retired to their Silesian estates, they live in Potsdam, in the very center of Germany's nationalist-military revival.

Commander of an army in the World War, the Crown Prince is now a well-known figure in circles of Berlin society and sport. He is frequently seen driving his enormous motor-car at high speed through the city, or passing out prizes at horse-shows, or enjoying himself at golf. During his father's reign, he rose up several times in more or less emphatic political opposition. But since the end of the war, practically nothing has been heard of his political interests or activities, except that in recent times he has expressed strong sympathy for Hitler and his movement. It would be wrong to say that the Crown Prince is unpopular; one could even say that in certain circles of society, the dashing and attractive sportsman was actually well liked. But it is also wrong to assume that he could become the center of a popular movement which would enable him, as sovereign, to lead the German people politically and economically out of their present misery. Politically, the Crown Prince is an unknown quantity, although he has already passed the age of fifty.

While the all-seeing court gossip could connect the name of Wilhelm II—whose family life was exemplary— with barely the slightest flirtation, the Crown Prince tends to follow his famous grandfather, Emperor Wilhelm I, in susceptibility to the charms of attractive women. But in the case of the first Emperor (who was also the first gentleman of Europe), the perfect tact with which he handled such matters kept the knowledge of his susceptibilities from spreading beyond 1 the most intimate circle.

Of the other sons of the Emperor, only Prince August Wilhelm has been mentioned in public more than occasionally. Originally, he was considered as the one imperial son who expressed especial interest in art and general cultural questions. Disappointment in marriage and material difficulties in the post-war era may well have aroused in him a sense of bitterness and loneliness, which helped to bring about his joining the Hitler party. At all events, he has been one of Hitler's most faithful followers for several years; he is a regular adjutant at the side of the present Chancellor. But not even his best personal friends believe that he would ever be considered as a candidate for the throne.

There remain in view the children of the direct line—the sons of the Crown Prince. They are still comparatively young, and the German public knows practically nothing about them.

Prince Louis Ferdinand, the second son, is the best-known. For several years he lived in South America, and now is one of the countless automatons which build the motor-cars on Henry Ford's assembly-belt. If this popular prince is ever destined to assume a leading post in Germany, these years of study and travel, which have brought him so close to the realities of modern life, will be of the greatest service.

One thing must not be forgotten. If the Crown Prince is to mount the German throne, a formal renunciation is necessary on the part of Wilhelm II; and even if the old ruler could decide upon such renunciation, it would be an arduous move for an enterprising Empress. In the same manner, the son of the Crown Prince could assume the throne only if the Crown Prince himself would renounce the position. The Crown Prince is a man in his best years, and would certainly find such an unselfish procedure most difficult.

The deciding moment in the question of Germany's return to monarchy will come when President Hindenbuirg leaves office. In case the Chancellor and his party at that time decide for a restoration of Kaiserdom, they will have to choose one of the personalities mentioned here. But, if they decide on the election of a new president, the royalist hopes of Germany will remain buried for a long time to come. And under the type of absolute dictatorship along the Italian model which Chancellor Hitler is trying to build up for himself, the role of a monarch would be a very shadowy one, offering small inducement to a man of stature and personal political ideas.

This much is certain at the present time: that among the royal persons now available for the throne, none has become the center of popular enthusiasm. and that none seems destined to be the focus of a dream of monarchy.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now