Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

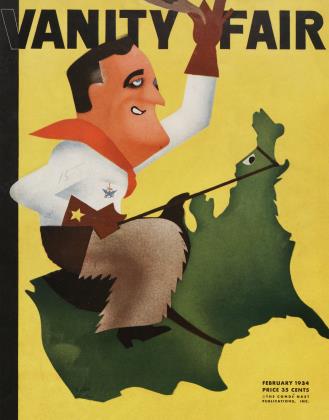

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowA Valentine for Mr. Woollcott

DOROTHY PARKER

When I was young and charming—at which time practically nobody in the

land was safe from buffalos—the literary quarters of the town were loud with indignation against the dark and infrequent crime of log-rolling. Indignation, in fact, is a rather small word for the fury of feeling that spread and deepened until it became generally accepted that anyone who would praise a friend would steal a horse. You might set fire to widows, deflower orphans, or filch the flags from soldiers' graves, and still be invited to all the literary teas; but if you admired, in print, the traits and achievements of any member of your acquaintance, your jig was up. And if you couldn't stand up and put a revolver to your head, like a man, the only thing for you to do was to streak for Port Said, and become Hoppy Dick, the human derelict.

The fear of becoming a log-roller was put into me during my formative years, and there was a good long stretch during which, in my endeavors to keep clean of the ugly charge, I said only the vile of my nearest and dearest. If there were not enough outrageous things to be said in honesty, I made them up and swore by them. It was nice work, while it lasted, only, pretty soon I didn't have a friend in the world and became known as the Lone Wolf. Then 1 found that, with a refreshing suddenness, the tumult against log-rolling had ceased, and it was as safe to write honestly of a friend as if you were in your own bed. I do not know quite what happened. Perhaps, as your morning paper will tell you, everything is ever so much better now, or perhaps people found they had enough troubles without bothering their curly heads over the tributes wrung from one writer to another. Anyway, there is little or no shuddering about log-rolling going on these days, and it is with a blessed sense of emancipation that I may here set down a few facts in the life of Mr. Alexander Humphries Woollcott—whom I have known for fourteen years and never a cross word—without feeling that if I don't say he is illiterate, venal, and a love-child, I must live out my days a marked woman.

Alexander Woollcott was born in Phalanx, no kidding, New Jersey, in a gently strange community of which his grandfather was a founder. The idea was that everybody was to live in one vast establishment, which still stands large as life, and raise their own food and live happily' ever after; and so, apparently, they did. It seems to have been an enchanted existence, perhaps due in part to the presence of a beguiling gentleman who got back to Mother Earth by painting his room in three great stripes of brown, green, and blue, and taking daily sand-baths. The father of the infant Alexander was a man of introspective nature who kept getting his feelings hurt and moving to another town, and dutifully the family went where he did, even unto Kansas City. Nor has Kansas City forgotten that the boy who was to grow up to be co-author of The Channel Road once dwelt there; today a splendid bulldog named Alexander Woollcott, to the very point of spelling it with all those double letters, is one of the prides of the place.

We next find our hero in Philadelphia, I forget by what process of reasoning, where he lived alone through his high school days and supported himself by his precocious pen. He reviewed books, and there was some pretty fast work done about taking them around the corner and selling them as .soon as he had damned their contents. Once he entered an essay contest, won in a walk, and was awarded a gold medal, which he quickly sold, for sentiment was not yet in him. In Philadelphia he met some enthusiastic alumni of Hamilton College, so that was where he went next and back there he still goes whenever he is allowed time. It is to Hamilton, I think, that he will go when he dies, if he is good.

Then He came to New York—don't we all?—found that he was a reporter and ripped his nerves to fringe working on murder cases. So they made him dramatic critic, possibly to give him a chance to sit down. Then came That War, which occasionally creeps into his writings, and then he came back to more dramatic criticism, and then he began shooting out in all directions. But always his love, his sweet, his ladye faire is the stage, and he cannot stay long away from her. With his friend George Kaufman he wrote The Channel Road, of which 1 can only say that I didn't see it, and later he was persuaded—I imagine someone dropped a hat—to tread the boards himself in a play called Brief Moment, which, in an engaging manner, he stole right from under its star's pretty little nose. His part required him to lie around on couches a good deal and utter wearied epigrams and experienced advice—a role of which Mr. Donald Ogden Stewart remarked that no matter how thin you sliced it, it was still Polonius.

Still he is faithful to the stage, although his bi-weekly outings with her wicked stepsister, the radio, might be considered mild cheating. He loves to talk over the radio, he actually loves it; and certainly his civilized gossip along the air has gained him thousands of friends—which in his case was painted lilies to Newcastle. But tin; play is ever the thing with him, and his and Mr. Kaufman's The Dark Tower, is, it seems to me, as skilled and entertaining an exhibit as you will find in the town. And I wish to God that were higher praise.

Apart from his work—or perhaps because of it—he has, I think, the most enviable life I know; and it is all his own doing. He plans the pattern of his days, sees its whole fine shape and all its good colors, and then follows it. He is predisposed to like people and things, in the order named, and that is his gift from Heaven and his career, also in the order named. He has, I should think, between seven and eight hundred intimate friends, with all of whom he converses only in terms of atrocious insult. It is not, it is true, a mark of his affection if he insults you once or twice; but if he addresses you outrageously all the time, then you know you're in.

Alexander Woollcott has been told he looks like Chesterton, but he seems to me to resemble less Chesterton than one of his paradoxes. He is a vast man, not tall; mightily built, with tiny hands and feet. Caricatures of himself always delight him, no matter how they were intended. His apartment is hung with black-and-white libels of Woollcott. That apartment is just what you've always wanted, and so, I am sure, has he. It stands over the East River, so that through a great sheet of plate glass you can look across to Welfare Island or look down and see the corpses drifting lazily by, and there is one whole blessed room given over to shelf above shelf of books about murder. Murder is Mr. Woollcott's other love; it is, to date, unrequited.

(Continued on page 62)

(Continued from page 27)

It is a shade sad, for one who lives from hand to sheriff, to know that Alexander Woollcott has that apartment, all for his own, and then keeps leaving it. In the first place, he is encumbered with a passion for rather huge dogs, and as soon as he enters delightedly into their possession, he has to take country houses for them. And, besides, he travels like a forest fire. Turn your back, and the man is in Shanghai. He sails invariably with a bleeding heart for those he leaves behind, and three days out he has a complete new outfit of dear ones. It is his boast that, were he lifted from the thousand arms of his friends and dropped in some small, strange town, in two weeks the affairs of that town would be his affairs and if someone mentioned New York to him, he would have to think for several minutes before he could place it. But I think, myself, he ought to smile when he says that.

He is at the same time the busiest man I know and the most leisured. He even has time for the dear lost arts— letter-writing and conversation. It is a good thing to hear real, shaped, shining talk, in these days when halves of sentences are left hanging miserably in the air, with nothing better to sustain them than an "at least, I mean," or an "oh, you know." And it is a good thing to know that someone is writing letters and, as a reward, receiving them. It makes you feel that all that is being taken care of, and so you can just sit back and take off those heavy shoes. The Lord alone knows where he finds the hours for all he does, though I suppose that those who have always enthusiasm have, also, always time. Alexander Woollcott's enthusiasm is his trademark; you know that never has he written a piece strained through boredom. Sometimes, indeed, there are those who feel that he lets himself be carried away, though in a winning way, and gives perhaps over-generously of his sentiments in his printed words. It was Howard Dietz, God bless him, who, on reading one curiously lace-edged bit of prose, referred to its author as LouisaM.Woollcott.

Alexander Woollcott likes to work; I give you my word, he likes working. He does it rapidly and surely and, you know darn well, expertly. And he likes it. That is the worst thing 1 know about him; to me, the sight of someone enjoying work is the affront direct. Well. That's the way he is. He is my friend—he can do no wrong, I suppose. Maybe it would be better to slide over that side of him, if the phrase does not conjure up too difficult a picture, and go on to the best thing I know about him. That is that he does more kindness than anyone I have ever known; and I have learned that not from him but from the people who have experienced it.

(Note to Mr. Wool I coll: Dear Alex, now will you marry me? Dorothy.)

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now