Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWhile Woollcott burns

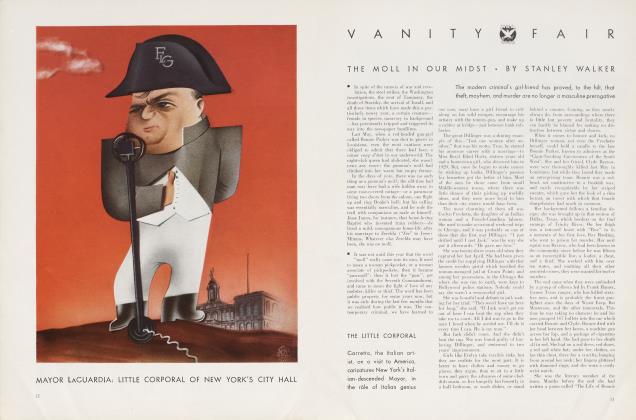

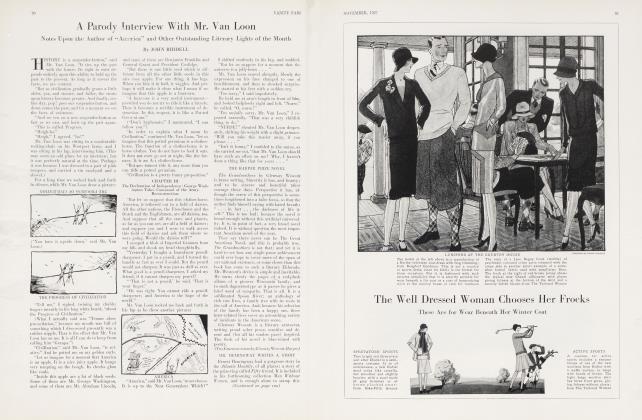

JOHN RIDDELL

(NOTE: In view of the ever-increasing popularity of America's Public Raconteur No. 1, in the magazines, on the stage, over the air, and most recently between the covers of a national best-seller, the editors of Vanity Fair this month have requested their staff gossip, John Riddell, to prepare a similar collection of his own random notes and jottings, in the stone-skipping manner of that faintly effervescent selection, "While Rome Burns," by Alex a n de r Woollcott.)

WHEREIN it is related how the discovery of a dismembered head on the floor of a parlor in Sussex gave rise to the odd supposition that its owner had been faintly murdered.

"IT MAY BE HUMAN GORE": I

THE DISAPPEARANCE OF THE INVISIBLE ABSENTEE. It is doubtless some years since that regrettable August morning when, it is rumored, the somewhat testy nature of Miss Lizzie Borden prompted her to indulge in a series of rather sanguinary experiments upon the persons of her doubtless faintly startled parents, and thus evoke a drama which was destined to set the tongues a-wagging over every breakfast tray in America, ere the slightly incredible case wound its way into the archives of history: yet the vaguely blood-stained hatchet with which Miss Borden is said to have performed her mulish dissection, to what I have no doubt was the lofty disapproval of the more conservative community of Fall River, was probably no less conclusive a lethal weapon than the kitchen cleaver with which someone had the deplorable taste to sever the head from the body of an obscure Brooklyn dentist who bore the remotely incredible name of Dr. Mops.

This, then, my dears, is the tale as it was told by Harpo Marx to Katharine Cornell and by Katharine Cornell to me, told on a fine May morning whilst sipping an aperitif in a rickshaw bowling down the Rue de la Paix in Moscow with Kathleen Norris, who must be, I think, so disassociated in the public mind with ruffianly behavior and raffish dissipation as to render any comment on her own lack of part in the affair a work of supererogation, told, I may add, with such patent relish for the homicidal details that your timorous correspondent was inclined to suspect for a wild moment that the narrator might even then be contemplating some similar violence upon what George S. Kaufman has referred to as this not inconsiderable shadow of a former sylph, and consequently I am setting it down here among the, as Edna Ferber caddishly points out, faintly familiar stories of similar macabre indiscretions which your lugubrious correspondent has had occasion to note from time to time in these random jottings, ere he totters into what someone—was it Dorothy Parker?— refers to as his anecdotage, in the faint hope that perhaps Mr. Edmund Pearson or some other indefatigable delver into criminal lore sometime may find it convenient for his gory files. Where was I?

The discovery of this lamentable lapse in manners which someone had displayed toward the unfortunate Brooklyn molar chirurgeon was made by the late Dr. Mops's weekend hostess, a lady with the slightly repellent name of Mrs. Kiki Messersmith, who it seems had invited the unsuspecting dentist down to her home on Long Island, a mullioned-windowed manor-house known for reasons which escape me as "The Wuppery," in order to enjoy what subsequently turned out to be a complete rest. The erstwhile practitioner was discovered by Mrs. Messersmith the morning following his arrival, lying on his stomach in the center of a rather atrocious carpet in the dining-room; but in her explanation later to the slightly incredulous jury, Mrs. Messersmith stated that she had assumed that Dr. Mops was merely looking for crumbs of Cheddar cheese, for which he had a somewhat pardonable weakness, and that she had no idea be was even faintly dead. Her impression that he was not dead was strengthened by the fact that she recalled Dr. Mops had risen on one elbow when she entered the room and said distinctly: "Good morning, Mrs. Messersmith." Three days later, having occasion to glance again into the dining-room, Mrs. Messersmith observed that the body still lay on the carpet, but that the head was missing. Her suspicions were aroused.

The fact that the head was missing seemed to indicate that this was a clear case of suicide. This faintly obscure theory was borne out by the discovery of a note in the doctor's pocket which read: "This is a clear case of suicide. McNaboe L. Mops, D.D.S." A desultory search ensued for the head, however, and presently it was discovered in Mrs. Messersmith's black bombazine reticule. In the meantime, unfortunately, the body had disappeared. By the time they had found the body again, Mrs. Messersmith had disappeared. Mrs. Messersmith was later discovered operating a teashop in East Orange, N. J., but, by the time she was found, both the body and the head had disappeared, and as a result the case was thrown out of court for lack of evidence, followed by Mrs. Messersmith.

When Mr. Pearson gets to work on this case, I trust he will not overlook one or two minor details which have somewhat enhanced its very slight interest for me. I have had occasion elsewhere to mention how greatly such mysteries are enriched by the flavor of the names involved. F or example, the tea-shop which Mrs. Messersmith operated was named—with such a spasm of quaintness as rather to revolt this old stomach—"The Teentsie-Weentsie Shoppe". Finally, I ask Mr. Pearson in particular to note, in his doubtless engrossing history of the trial, the name of an obscure young barrister who defended the suspect with such rustic eloquence that he quite overcame the natural prejudice which his disheveled appearance and gangling cordy figure aroused in the faintly meticulous jury, an appearance which some of them, no doubt, had occasion in later years to recall to their grandchildren. You see, the name of this awkward solicitor "was Abraham Lincoln.

Continued on page 62

Continued from page 16

THE story of on answer, being an effort to break the previous all-time long-distance record for anecdote-inflation, likewise held by your space-consuming correspondent.

LEGENDS: II

THAT WAS MY wife—Then there is the answer which someone—was it Mrs. Patrick Campbell?—once made when Paul Robeson, if memory serves, asked her: "Who was that lady I seen you with?" I was reminded of this answer the other afternoon whilst browsing through a volume by Joe Miller at Wit's End during that eldritch hour when the enchanted rooftops of Manhattan invariably recall those faintly nostalgic spires beneath which your doddering correspondent, then but a mewling sophomore in his salad days at Hamilton College, was wont to sit in an execrable pair of pantaloons upon the steps of the Theta Delt house, a conspicuous position from which, the brothers intimated, I might do worse than remove myself if we were to have any freshman delegation at all that year, and there speculate somewhat idly upon that magic moment when I first had seen the llamalike'Lillian Gish in Camille, a haunting performance as exquisite and fleeting as that other in a Tokyo theater when Onoe Kikugoro, a sensitive and subtle thespian, put me in mind, by the sheer artistry of his pantomime, of a very different moment in the frozen mud near Savenay when the monstrous winds of war had swept a number of us together at a time when the I burning question on everyone's benumbed lips was somewhat different from the question which prompted that flippant answer which f have had occasion to repeat at odd moments from Moscow to China, whilst trundling in a rickshaw along the Avenue of Banners in Chicago, or whilst eating a souffle under the midsummer stars at Monte Carlo, an answer from which, though subsequently disinclined to recall it, its owner must have derived at the time some slight malicious pleasure, an answer of which it ! could be said that it had the quality of greatness, an answer which I note with ill-concealed satisfaction has already consumed two and a quarter columns of fine print while getting to the point, an answer which in fact has shattered my own previous record for literary suspense of one and seveneighths columns, an answer which I have taken so long in telling, as a matter of fact, that by this time I have even forgotten it myself.

Footnote: The foregoing dispatch evoked such an agreeable shower of responses from eager correspondents, who sought to enlighten this old memory, that I am forced to conclude that the classic rejoinder must be another of those specimens of American folklore in the making which recur now and then, bobbing up every so often, whenever I am stuck to till a column.

PORTRAIT of the author as a jigsaw puzzle, wherein he proves, to his oivn not inconsiderable bewilderment, that if you take away all the pieces there is no puzzle left at all.

SOME NEIGHBORS: III

"PUBLIC RACONTEUR NO. i"—A portrait of Mr. Woollcott? I am reminded of that urchin remark made once, as 1 recall, by Dorothy Parker, who, queried by some mulish rustic—could it have been Harpo Marx?—as to her presence in his barnyard, was moved to reply somewhat loftily: "They ain't nobody here 'ceptin' us chickens."

Then there was the occasion when Anne Parrish, Charles MacArthur, Rebecca West, F.P.A. and your inevitable correspondent were discovered in the closet of their host whose name, for reasons which escape me, was Harold Ross. "Believe it or not," explained one of the number, of whom it might he said that he had the qualities of greatness, "we are only waiting for a street-car."

Or that other to-be-forgotten moment when Alice Duer Miller, loping up the aisle of a theater for a dash of nicotine, was accosted by a sidewalk mendicant whose name, as I recall, was Mr. Sullivan. "Could you tell me," inquired Mr. Benchley, if it was he, "which is the other side of the street?" Mrs. Miller obligingly pointed out the opposite curb. "Sure an' begorra." replied, I have no doubt, Mr. Connelly, "an' they told me over there that it was this side!"

Also I am inclined to doubt, for example, whether I am any longer capable of such blistering scorn as animated Edna Ferber when her dinner-partner—could it have been Herbert Bayard Swope?—turned to her and inquired: "Do you mind if I smoke? ' Miss Ferber's reply was devastating. "I don't care if you burn," she said.

But all this is not a portrait of the author, you murmur faintly? This is merely a series of portraits of the circle of ink-stained wretches who surround him? Well, my pretties, it seems there is an old text-hook theory which states, if memory serves, that when a tree falls in a forest and there is no one around to hear it, the tree makes no noise. To be sure, I do not know how you would set about to prove it by Alexander, if memory serves, Woollcott.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now