Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowPHOTOGRAPHY

PAUL 0UTERBRID6E (Grey Art Gallery and Study Center, New York, a retrospective selection, September 21-October 15; Robert Miller Gallery, New York, September 8-October 1). During the past decade Paul Outerbridge has been transformed from a neglected commercial photographer into a lesser modern master. His fastidious commercial images and his once unacceptable nudes are now exhibited together, the subject of half-baked scholarly critiques. It’s an odd body of work, and its very oddity raises questions about the nature of photographic creativity and the allure of the eccentric artist.

Outerbridge’s life story is a patchwork saga of natural talent, quick success, arty delusions, bad judgment, failure, and isolation. His nervous sensibility sent him to Bermuda as a very young man to recover from his exhausting social life; it also pushed him to commercial success, in 1922, while he was still a mere pupil of photography. Seen in the context of American and European modernist photography, Outerbridge’s black-and-white work of the 1920s was in perfect sync—immaculate, highly formal compositions of everyday objects and fashion accessories. Even the developing international avant-garde acknowledged him, and he was included in the important “Film und Foto"' exhibition in Stuttgart in 1929.

But Outerbridge suffered from self-intoxication. His demanding temperament ruined his lucrative job at Paris Vogue, and the photography studio in Paris where he was a partner collapsed after less than a year. By 1929 Outerbridge had wrecked his finances and his marriage, and stymied his career.

After four years in Europe he returned to the U.S. and became a recluse, with a seven-foot snake as his constant companion. Locked in his family’s dilapidated New York country house, he toiled away writing treatises on “feminine beauty’’ and perfected the difficult, expensive, and time-consuming Carbro-color printing process. By the mid-1930s he reemerged an even more successful commercial photographer with an expanded clientele. No longer the images of the perfume and masked ball set, his new subjects were lighthearted housewives and holiday pies. Although his elegant aesthetics still held, many of these color commercial images (made for House Beautiful) are early representations of the straight-arrow American domesticity that reached its height in the 1950s.

At the same time he was also turning out pictures of fetishistic female nudes based on his “theories’’ of perfect womanly beauty. These are the images that sparked his rediscovery. The most famous among them conform to our own nostalgic fantasies of the elegant, decadent 1930s, nudes decked out in top hats and high heels. He photographed uncostumed nudes in greater number. In his writings, Outerbridge analyzed the female figure into its component parts, defining optimum appearance and proportions of noses, breasts, thighs, etc., as if they could be made to order for him. This mechanistic objectification makes his nudes look more like anatomical specimens than erotic fantasies.

The photography world has become infatuated with Outerbridge for other reasons besides his idiosyncratic style. The finely detailed, luminous Carbro prints have a subtlety and an eerie realism to them unmatched by any other process. And the bleak grotesquerie of his failed eroticism is compelling, pinching the sensitive cord of our cultural fascination with and prudish abhorrence of naked women. Even his commissioned work is sometimes imbued with his kinky sensibility; a length of toilet paper snaking across a field of blood red roses looks more animated than the lifeless model’s hand that caresses it.

Outerbridge’s two seemingly opposite bodies of work raise important questions. What aspect of his photographic process can be defined as “creative” when both his vision of well-ordered domestic life and his unsavory nudes are obvious fabrications? Who acquired the nudes? If they were the same people who also subscribed to the all-American life style he was selling, then how do we determine where to draw the line between the two bodies of work?

All of Outerbridge’s work (like most photography) is an amalgamation of his attitudes toward the tangible real world and cultural stereotypes that shape our perceptions. That elusive interaction is ultimately more telling and more significant than the continuing squabbles over photography’s (and Outerbridge’s) artistic status.

CAROL SQUIERS

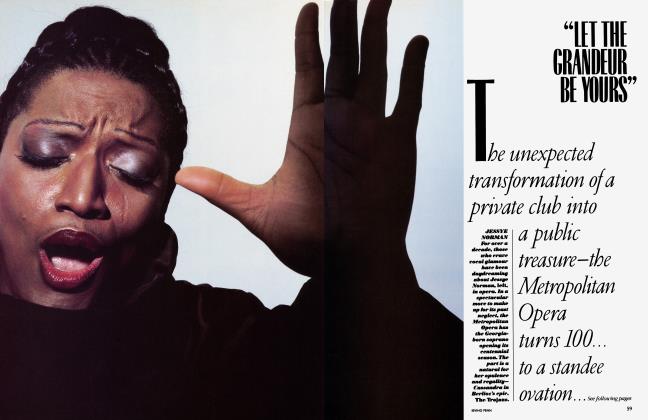

■ MARILYN MONROE, J. Edgar Hoover and Elsa Maxwell are only some of the opera buffs who liked their Verdi hot. These and other glittering moments are captured with verismo in the Metropolitan Opera Centennial: A Photographic Album at the energetic International Center of Photography (New York, September 27November 13).

With a new staff and a new group of Financial backers, the photography gallery called LIGHT (New York) casts just that this month on Eikoh Hosoe’s new sensuously abstract photographs.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now