Sign In to Your Account

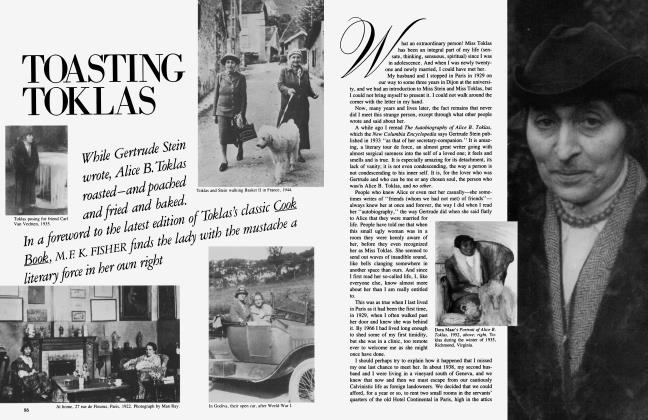

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowSylvia

LEONARD MICHAELS

An exclusive preview of LEONARD MICHAELS's dark memoir in progress. In this excerpt, Michaels, author of the acclaimed novel The Men's Club, arrives in Greenwich Village in 1960, a grad-school dropout yearning to write fiction. He meets the brilliant, black-eyed Sylvia Bloch and begins a romance that evolves into a tragic marriage. When he met Sylvia, he writes, "the question of what to do with my life was resolved for the next five years"

I

In 1960, after two years of graduate school at Berkeley, I returned to New York without a Ph.D. or any idea what I'd do, only a desire to write stories. I'd also been to graduate school at the University of Michigan, from 1953 to 1956. All in all, five years of classes in English literature and I wasn't a scholar or a writer or anything except an overspecialized man, twenty-seven years old, who could give no better account of himself than to say "I love to read." It doesn't qualify the essential picture, but I had a lot of friends, got along with my parents, and women liked me. In a vague and happy way, I felt humored by the world, and, whatever my predicament, I wasn't yet damaged by judgment, though I inflicted it on myself every minute. I had nothing else to do.

A few days after arriving in New York, I went to see Naomi Kane, a good pal from the University of Michigan with whom I'd spent innumerable hours drinking coffee in the studentunion cafeteria, center of erotic social life and general sloth. She lived in Greenwich Village, on MacDougal Street near the comer of Bleecker. From my parents' Lower East Side neighborhood, ] rode the F train, banging through the rock bowels of Manhattan to the Wesl Fourth Street station. Then I walked.

It was a hot Sunday afternoon in June. Village streets carried slow, turgid crowds of sightseers, especially MacDougal, a main drag between Eighth and Bleecker. The famous Eighth Street Bookshop at one end, the famous San Remo bar at the other. I'd walked it a thousand times during my high-school days when I'd gone with a girl who lived in the Village, and later all through college at N.Y.U. when I'd gone with another who lived in the Village. But I'd been away for two years. I hadn't seen MacDougal Street become jammed with stores and coffeehouses or felt the new apocalyptic atmosphere. Around then, Elvis Presley and Allen Ginsberg were the kings of feeling, and the word love was beginning to sound like a proclamation with implications similar to kill. I saw a blunt admonition chalked on the wall of the West Fourth Street station: "Fuck hate." Weird delirium was in the air. I sensed it even in the sluggish, sensual crowds as I pressed toward the sooty-faced tenement where Naomi lived.

The street door had no lock or buzzer. I pushed in, into a long and very narrow hallway, painted with greenish enamel that gave it a dingy, cold, sickish glare. The hallway went straight through the building, ending at the door to a coffeehouse called the Fat Black Pussy Cat. Urged by the oppression of the walls, I walked quickly and, just before the coffeehouse, came to a stairway with an iron banister. I climbed six flights and walked down another narrow hallway, dim and gloomy; brittle waves of an ancient linoleum floor crackled beneath my steps. Naomi's door, like the entrance to some kind of office, had a clouded glass window. I knocked. Naomi received me with a great hug.

I took in the small, squalid living room behind her, dominated by a raw brick wall. The floor was exposed thick, rough planks, like the floor in a warehouse. She said, "Don't make wisecracks. The rent is forty bucks a month." She then introduced me to her roommate, Sylvia Bloch, and the question of what to do with my life was resolved for the next five years.

Sylvia was slender and very tan, with straight, black-black, dense, shining hair. It fell below the middle of her back. Low bangs obscured her eyes and made her look shy or modestly hiding; also shorter than she was. She was about five six. Behind the bangs her eyes were quick and brilliant, black as her hair. She had a long fine neck, wide shoulders, narrow hips, and delicately shaped wrists and ankles; a figure reminiscent of Egyptian statuary. She wore an Indian dress of light cotton, with an intricate flowery print. Apparently she'd stepped out of the shower a moment earlier. She said hello while brushing her hair with deep slashing strokes, tipping her head right and left, tossing the wet black weight. Then she quit abruptly and dropped onto the couch, brush still in hand, as if she'd never move again.

We sat in the living room drinking iced tea until Naomi's date arrived, and then we all went out, staying loosely together, strolling against the slow flow of sightseers up MacDougal to Washington Square Park. Naomi whispered, "She's not beautiful, you know," as if it were too obvious that I'd been deranged by Sylvia's flashing exotic effect. Since Naomi was one of my sharpest friends, I took the remark seriously, but there is no use in such correction no matter who offers it. Conceding to the inevitable, Naomi said, "She is very smart."

We intended to have dinner together and maybe go to a movie, but Naomi and her date disappeared, deliberately abandoning Sylvia and me in the park, like social liabilities, both of us too stupid with feeling to be any fun. We walked like zombies and hardly talked, wandering through the crowds in the dreamy heat. Though we'd met less than an hour before, it seemed we'd always been together in the plenitude of this moment. Neither of us tried to be flirtatious or charming. We barely glanced at each other, just stayed close, and eventually wandered back to the tenement, down the dismal green hall, up the six flights of stairs, and into the squalid apartment like a couple doomed to a mysterious, sacrificial assignation. We made love until afternoon became twilight and twilight became black night.

Through the tall, open window of the living room, we saw the nighttime sky and heard the people proceed along MacDougal Street, as in some mad carnival, screaming, breaking bottles, wanting to hit, needing meanness. Someone was playing a guitar in another apartment. Someone was crying. Lights crossed the walls and ceiling. Radios were loud. Everything in the city made its statement nearby, even within the living room, it seemed; but none of it had to do with us, naked on the couch against the brick wall. The couch was Sylvia's bed, just wide enough for two. Now, as if released by sex into simple confidentiality, we talked.

She told me that she was nineteen and her parents were dead. Her father, who had worked for the Fuller Brush Company, died of a heart attack. Her mother, who had been mainly a housewife, did well playing the stock market as a hobby. She died of cancer. A time followed, during which Sylvia lived with an aunt and uncle in Queens, when she thought she was going crazy. She could describe none of it. When she decided to go to college out of town, she applied to Michigan and to Radcliffe, because her boyfriend was at Harvard. Though she was much brighter than her boyfriend, she wasn't admitted to Radcliffe. She supposed Radcliffe could pack every class with black little German Jews who tested high, but she took the rejection personally, especially since it marked the beginning of the end of things with her boyfriend. Her new boyfriend worked in a local restaurant. He was a tall, good-looking Italian, but she preferred the frail blond at Harvard. The Italian would show up tonight, she said. His swimsuit was in the apartment.

As she went on about how she had met Naomi at Michigan, and how much she adored Naomi, I thought of the boyfriend who would show up tonight and I wanted to flee. But Sylvia said no, got out of bed, and searched the apartment until she found his swimsuit. She hung it on the doorknob, outside the apartment, by the jock. It looked like a disemboweled rabbit, dripping white stringy guts. We lay as before in the loud, balmy darkness, and after a while we heard his trudge on the stairway and along the linoleum to the door. From the weight of his steps, I figured he could break my head. The steps ended at the door, less than ten feet from where we lay. No knock followed. Was he contemplating his swimsuit? The message was clear. I supposed he wasn't a moron, but even a genius might kick in the flimsy door and make a moral scene. He said, "Sylvia?" His voice carried fatigue and pain, no deadly righteousness. We lay still, hardly breathing, disintegrated in the darkness. Moments passed. Again the question, "Sylvia?" Then his steps went away. The burden of his voice stayed with me. I was sorry for him, feeling inadvertently responsible for his pain; but mainly I was struck by Sylvia's efficiency in exchanging one man for another like a gambler shuffling cards.

Would it happen to me too? I imagined it would, but she lay beside me now and the cruel uncertainty of love was only a moody flavor. I pushed the image of the swimsuit out of mind. We turned to each other renewed by the thrill of betrayal. Afterwards, Sylvia got out of bed and sat on the window ledge, outlined against the western skyline of the city and the Jersey shore. It seemed, by putting a distance between us, she wanted to collect a power of decision in herself, or to understand what decision had been made. Years later, in fury, she said, "The first time we went to bed. The first time..." She resurrected the memory with crushing bitterness, saying we'd done extreme things and I'd made her do them.

At dawn, having slept not one minute, we went down into the street. The residue of the night was strewn along the curb and was overflowing metal trash cans, shining and garish, beginning to stink in the returning light. The broken, heaving sidewalks oozed a steamy glow. There was no traffic or people. Between dark and day, the hard city stood in stunned, fetid slumber.

Thus, in an aura of peace and desolation, we walked until we found a bench in a small grassy area set back from the street on Sixth Avenue, and we sat there staring into each other's eyes adoringly, yet with a degree of reserve or concern to see whom we'd been to bed with for the last ten hours. Sylvia then announced that she was leaving for summer school at Harvard the next day. Immediately I remembered her former boyfriend and felt jealous. Though I had no right or reason to expect fidelity, and perhaps didn't even want it, I remembered that she had said she liked his blond looks, his kindness, his gentle and Gentile old-money manners, and I anxiously supposed that I would lose her to him. But then she asked if I would move up to Cambridge and live with her. Her face was held high, stiff with anticipation, as if to receive a blow.

I see her. Maybe I know what I'm looking at.

Then I was taken by highlights along her cheekbones and the slack, luscious expectancy in her lower lip. How timidly she asked the question, how she waited for my answer. I liked the Oriental cast of her face, the smoothness, height, tilt of its bones, the straight black hair against its length. Steep, stylized clarity; a look of cool dark blood. Her bangs made her seem shy, like a kid. She was afraid I wouldn't say yes.

A week later I took the train to Boston. Sylvia moved out of her dormitory. We found a room near the university in a big house of solemn furniture and shadowy passages.

I took the train. We found a room...

The truth is I wasn't sure why I was in Cambridge except that she wanted me to be there and I had no reason to be elsewhere—no job, nothing to do, only a desire to write stories, which, I sincerely believed, was nothing to do. It wouldn't pay. It wasn't useful or real work. When I looked at Sylvia's face, I liked what I saw, but I wasn't sure of anything else.

The room we rented was in a house full of things, heavy and stolid, with sheets thrown over them. Blinds were drawn, doors were shut; the whole place seemed defended against light and air. A man in his sixties lived alone in the house, unwilling to use his things or fully to acknowledge their existence, but they were much felt, hulking in corners, looming against walls. Even the shadows, like more furniture, seemed to have material being, loading rooms, choking halls with their obscure silent presence.

Our room was on the second floor. It contained a grand dresser, some lavishly upholstered chairs, a night table, and a giant bed. All wood surfaces were veneered in hard, slick brown. Pulling back the bedcovers demanded a strong grip and snap. Sheets were tucked in tight, making a hard flat field of white to resist the most elephantine buttocks. A principled bed, enemy of comfort, perfect for a corpse. The mattresses were unusually thick, like a fat luxurious heart sealed in denial. They suggested an emblem of the house— bulging, ungiving, dark, still.

When we came downstairs the first morning, the owner was waiting for us. He was a bald man, gaunt and flat as a plank, sitting in a high-backed chair in the parlor, with his long platter face staring at the floor. Before he said a word, I felt his disapproval and a vast pool of sorrow beneath it.

"You two will have to go.''

Why he had rented us the room in the first place I don't know, but it may have struck him in the middle of the night that we were doing things to each other's naked body, though we struggled to be quiet, fucking slowly, in a manner consistent with the grave dignity of his ethical domain. His words—"You two will have to go''—were drawn against the bitterest moral constipation. Except for novels and poems, they were my first intimate experience with the spirit of New England.

We went directly back up to our room, packed, made no fuss, and were soon adrift in the busy, hot, bright streets around Harvard Square. Sylvia refused to go back to her dormitory, though—being together—we had no place at all to go. The beauty of the day made everything feel worse, even hopeless. It seemed our romance was blighted. Storefronts and windshields flashed threats, and everyone but us walked with healthy, energetic purpose, as if they belonged here and were good. We had bags, no place to go, and were bad. We had each other with heavy hearts. Then, after phoning some friends, we learned of a house where three Harvard undergraduates lived, in a workingclass neighborhood far from the university. Maybe they'd rent us a room. We went there. It was an ugly, fallingdown, sloppy, happy house. One of the men, Clive Miller, began talking to Sylvia, the moment they met, in baby talk. She said, "Hello," and he said, "Hewo," with a goofy grin. She thought Clive was hilarious, but, more than that, she loved being treated like a little girl in a house full of men. The others treated her the way Clive did, more or less, but then she herself inspired it, so darkly sensuous and shy. Also the bangs, remarkably long, behind which she hid and looked at the world with her black, brilliant eyes.

In the mornings, when Sylvia went to class, I tried to begin writing stories. The room was narrow and hot and, being just off the kitchen, noisy. Sylvia studied in some library at Harvard. Though there were irascible moments, when we whispered angrily at each other in the hot compression of the room, they seemed attributable to its airless weight and mosquitoes; nothing personal. Through most of the summer in Cambridge, Sylvia and I were happy.

One afternoon, waiting for her to return from class, I saw her far down the street, walking toward me as I sat outside the house. I wondered why she walked so slowly. She walked even more slowly when she noticed that I'd seen her, and then I noticed that her right sandal was flapping and dragging. The sole had tom loose. At last she came up to me and showed me how a nail had poked up through the sole. She had walked on that nail all the way home, sole flapping, her foot sloshing in blood. What else could she do? She smiled pathetically.

She could have had the sandal repaired. She could have walked barefoot. As I protested, her smile went from pathetic to screwy. Perturbed. Injured. The source of pain was no longer the nail. It was me. For days thereafter, Sylvia walked about Cambridge stubbornly pressing the ball of her foot into the nail, bleeding freshly, refusing to wear other shoes. Finally, after much arguing and pleading with her, she let me take the sandal to be repaired. I was grateful. But she was not grateful and I was not forgiven.

Sylvia would begin breaking things. I'd try to stop her. She would twist loose and come flying at me, and then, as the violence intensified, it sometimes became sexual.

II

"Go. I don't love you. I hate you. I don't hate—/ despise you. If you love me, you'll go. I think we can be great friends and I'm sorry we never became friends.''

"Can I get you something?''

"A menstrual pill. They're in my purse.''

I found the bottle and brought her a pill.

"Go now.''

I lay down beside her. We slept in our clothes.

(Journal entry, December 1961)

III

At the end of the summer we returned to New York. Naomi moved out of the MacDougal Street apartment. I moved in with Sylvia. By then we were fighting daily and had become ferociously inextricable. Sometimes, directly after fighting, we had sex. For me, it was a new, hideously exciting thrill. In the middle of some trivial disagreement, Sylvia would begin breaking things. I'd try to stop her. She would twist loose and come flying at me, and then, as the violence intensified, it sometimes became sexual. Afterwards, she always slept and neither of us ever mentioned what had happened. The sex, whether conventional or violent, was very frequent and usually more exhausting than satisfying. Sylvia told me that she'd never had an orgasm and, as if it were I who had always stood between her and that ultimate pleasure, screamed at me, "I will not live my whole life without an orgasm." She said she had had several lovers better than I was.

Soon after we moved into the MacDougal Street apartment, Sylvia began taking classes at N.Y.U., a few blocks away across Washington Square Park, to complete her undergraduate work. When she asked me what she ought to declare as her major, I said that if I were doing it over again I'd major in classics. I should have said nothing. She registered for Latin and Greek, ancient history, art history, and English. It was a maniacal program, since she had to learn the complex grammar of two languages simultaneously while living in squalor and fighting with me every day. She also had to read a lot of fat, dull books and write papers almost every week. I expected confusion and disaster, but she was abnormally bright and did well enough.

Because there was no desk in the apartment, she studied sitting on the edge of the bed in a huge mess of papers. We also ate dinner in the bed, usually noodles, a frozen vegetable, and orange juice, or we went out for a pizza or Chinese food. Neither of us cooked. My mother often sent us food, and three or four times a month we had dinner at my parents' apartment. One night, after dinner, my mother carried Sylvia's coat into the bedroom and quietly sewed up a tear in the sleeve. Sylvia thanked her and seemed pleasantly grateful, but later, in the street, she became hysterical with indignation. She felt she'd been humiliated. Thereafter, I went to my parents' for dinner alone, but I would always bring something back—fried chicken, steak, dumplings, cookies. Sylvia would eat. Once, when I was at my parents' place, Sylvia phoned to say that she'd slit her wrists. I left in a rush, but not before my mother had packed a bag of food—a dozen bagels, large jars of gefilte fish and matzo-ball soup, and a pound of potato latkes.

I hadn't wanted to rush back. I didn't believe she'd slit her wrists. But I couldn't be sure. In my frustration, I yelled at my mother for holding me until she could pack the food. Then I rushed to the subway. From the subway I rushed to the apartment and burst in, hot and wild, schlepping a huge bag of food, shouting, ''I don't give a damn if you slashed your neck."

She had in fact sliced her wrists very superficially. There was some bleeding, but there'd be no scars. When she began picking at the food, I felt relieved. She liked gefilte fish and latkes.

Because of our long, miserable fights, she often began studying after midnight. Sitting on the edge of the bed, with the remains of our dinner amidst her mess of papers, she'd hold the grammar book in her lap and flip the pages, glaring at them as if they were an irritating distraction from her real concern, which was me. She'd say I was "doing this" to her, starting fights, trying to ruin her chances, make her fail. She'd say it as she studied and then again, early in the morning, as she flung out of the apartment still wearing the clothes of the previous day, in which she'd slept, for maybe an hour, before leaving. Her long black hair bouncing, flying with her stride, her blouse crumpled and half-buttoned, her skirt twisted on her hips, she'd hustle through the Village streets to N.Y.U. like a madwoman imitating a coed.

IV

We were sitting on the bed after dinner. I was looking at a magazine, Sylvia was beginning to study. I commented on the beauty of one of the models in an advertisement. Sylvia glanced at the photo, then said, ' 'Your ideal of beauty is blue, slanted eyes.''

"So?''

Sylvia dropped backwards on the bed, pulled the pillows against her ears, and began sobbing and thrashing. Then she stopped, sat up, and said, ' 7 never went into detail about my sexual experiences."

(Continued on page 109)

Continued from page 79

I sat in silence and waited. She fell back again, made leering, hating faces, writhed like an epileptic, and then sat up and slapped my cheek and sneered, "I can't see why you don't adore me."

(Journal entry, December 1961)

In the throes of vile histrionics, her voice could suddenly become cool and elegant, and, with lovely phrasing, she'd make a witty remark, as if, even when she seemed out of control, every quality of the moment was clear to her—the hatefulness of her display as well as my startled appreciation and pleasure in her wit. Now it seems ridiculous and contemptible, considering the almost unrelieved misery of our daily life, that I didn't tell her to go to hell and leave, walk out the door, take the F train back to Mom and Dad; but she touched levels of aesthetic and sentimental disease in me as deep as anything in herself. I saw her as an amazing and precious mechanism, at the center of which certain springs and wheels— exceedingly fine—had been brutally mangled. Anyhow, something like that. The very repulsion I felt held me, closer and closer as it became more powerful, more insufferable.

A major cause of our fights was my desire to get off the bed after dinner and go into the tiny room adjoining the living room. It contained a cot, a desk chair, and a small, plain wooden table, which was shoved against the tall window. I sat at the table, looking out over a fire escape and across rooftops, with their chimneys, clotheslines, and pigeon coops, toward the Hudson River and the Upper West Side. Winds shook the window and penetrated the old loose putty, carrying icy air from the Hudson River to my fingers. They stiffened as I tried to write. My chin and the tip of my nose became numb. I'd hear Sylvia sigh as she flipped the pages of her book. Papers on the bed rattled. I could even hear the sound of her pencil when she made notes. I was only four steps away. Nevertheless, she'd become resentful, feeling rejected, excluded, lonely, then angry. The feelings were associated, maybe, with the death of her parents. With me out of sight, though only four steps away, she might have felt herself ceasing to exist.

After dinner I lingered with her on the bed, reading a magazine as she collected her notebooks, preparing to study. When she began, I'd begin to leave. Never in a simple, natural way, but with a sort of vague gradualness, I'd stir, lay aside the magazine, lean toward the cold room.

"Going to your hole?'' she'd say.

Sometimes I'd settle back onto the bed. I'll write tomorrow when she's at school. Maybe she'll go to sleep in a few hours. I'll write then. A small sacrifice, better than a fight. That in itself, however—my desire not to fight— could be an incitement. "Why don't we talk about this for a minute...'' To sound rational, when she was wrought up, was like a smack in the face to her. In response, she became totally irrational. She smashed our radio against the brick wall of the apartment. She threw the typewriter she had given me—"to help you write''—at my head. An Olivetti portable, Lettera 22. It struck a wall, then the floor, but was undamaged. I use it still. She also failed to destroy the telephone, though she tried many times.

I wrote, I wrote. After a while, I didn't know exactly why. The original desire, complicated enough, had become something like a grim compulsion. Writing felt like I was doing a job—almost. Hard work. I hoped it would justify itself, though I believed anything good that emerged in it belonged to luck. After all, how good could it be? I'd spoken only Yiddish until I went to elementary school. I was aware that Jews were as unwelcome to English sentences as to nice hotels and that it was probably impossible for me to pass as anything else. Syntax, tonal pressures, rhythms, vocabulary, images—anything might betray the manners and peculiar energy of an incorrect Jew. I'd fumble and blunder amidst racial subtleties inherent in a language not my own. This was no matter of mere correctness. To write in English was to practice self-betrayal in ways not even accessible to my understanding. I remembered incidents in graduate school when I'd felt discovered. Once, after a class in Renaissance literature, the professor returned a paper I'd written and asked, with embarrassed curiosity, "Are you Greek?'' Something in my written English wasn't English. He was sincerely curious and meant no harm. He himself was a Greek. I adored the man. He seemed sublimely sensitive and fine. His shirt collars, gray and frayed, bespoke spiritual purity; the books he carried into class also looked deeply used, softened by endless caressing, mauled by his love of them. "I'm a Jew," I said. "Oh," he said. Entirely inconsequential, a completely innocent exchange, yet I brooded over it for years.

Another incident, in a seminar on Pascal, was less innocent. The professor was from Oxford, visiting America for a year. I went to each meeting of the seminar as if it were an incomparable opportunity and privilege. Then, halfway through the term, during a discussion of a passage in the Pensees, I blurted out an interpretation without waiting for the minimal inclination of the professor's head which meant it was all right to speak. His expression remained impeccably unchanged as he said, "Yes, Mr. Michaels. Pascal is as clever as you." I didn't say another word. I imagined the professor had seen grotesque spontaneity in me. I felt shame, self-hatred, and enormous rage at him. Thereafter, I read Pascal on my own. British anti-Semitism, I decided, was the most insidious kind.

Sometimes while writing in the cold room, I'd become exhilarated, as if I'd transcended all barriers, cultural and genetic. A day later, rereading with a cooler eye, I would sink into the blackest notions of destiny. It was no good. I was no good. I couldn't write in Yiddish. In effect, I had no language.

"Going to your hole?"

I felt I was digging it.

V

Sylvia had pain in her shoulder. She lay in bed and asked me to rub it, but when I touched her she squirmed spasmodically and kept pushing my hand away. I kept trying to do it right, but she wouldn't stop squirming and wouldn't tell me just where to rub. Then she lunged out of bed and paced the room, rubbing her shoulder herself.

' 'I have a sore spot. A stranger could rub it better than you."

(Journal entry, January 1962)

Sylvia was often in pain of some kind, or else in a nervous, defeated condition, especially when she got her period. Then she'd lie on the living-room couch, our bed, and groan and whimper and beg me to go out and buy her Tampax. Invariably, this request came late at night. I didn't see how Tampax could ease her pain, but she would be so desperately insistent, whining and writhing, that it was very apparent there was no use in talking about it. She wanted Tampax. She needed Tampax. After midnight, I found myself in the streets looking for an open drugstore where I could buy Tampax. I always dreaded approaching the man at the counter and asking for it. I imagined he would think I was an exceptionally bizarre Village transvestite, but I did it, asking for Tampax in a low, hoodlumish voice to disguise my wretched embarrassment. I did it about half a dozen times before I detected the faint indication of a smile in Sylvia's lips, one night, and realized that having me buy her Tampax turned her on. Then I quit.

VI

I recorded our fights in a secret journal because, as they became increasingly violent, I was less and less able to remember how they started. In the middle of the shrieking, with Sylvia breaking things—once she pulled my shirts out of a dresser and began jumping up and down on them and spitting on them—I realized that I didn't know why it was happening, and—however much I actually participated, seizing her wrists and shrieking back at her, or holding her down on the bed while I said that I loved her and pleaded with her to stop—I was more like a stunned observer than a committed fighter.

Usually, after a fight, Sylvia collapsed into sleep, in her clothes. I would find myself ringing with anguish and confusion, terrifically awake. In order to salvage a degree of sanity, I began forcing myself to rethink the fight moment by moment until I remembered how it had started. Then I'd write it down.

I hid the journal in a space below the surface of the table in the cold room, where I wrote stories, none of which ever had to do with life on MacDougal Street. I didn't write about that until years later, and then very obliquely in one story, and I never talked about what went on between Sylvia and me with friends. I also never talked about it with my parents, but they had seen a lot during Sylvia's visits to their apartment and on the night of the suicide phone call.

My mother's way of trying to help was to send food, bags and bags of love. My father's way was silence and looks of sad, philosophical concern, but he also gave me money. The one time I tried, in a fugue of agonized incoherence, to tell him about things in full and explicit detail, he cut me off, saying, "She's an orphan. You cannot abandon her.'' He didn't want explicitness, didn't want the details. He couldn't bear listening to my description of a ghastly problem about which nothing could be done. He told me a few stories of tragic marriages between people he knew where a husband suffered the evil lunacy of his wife. The point was, I think, one lives with it. Nothing should or can be done. Whatever the character of their life together, the couple is an absolute condition, as immutable as the relationship of the sea and the shore.

VII

One evening, after another long, gruesome fight, Sylvia went raging out of the apartment to take an exam in Greek, saying she had no hope of passing, she would fail disgracefully, it was my fault, and she would get me for this. The door slammed behind her. I sat on the bed listening to her footsteps hurry down the hall, then down the stairs. I was becoming more and more deeply immobilized by shock and self-pity when, in a spasm of strange determination, I shook free of these feelings, got up, and went out the door after her. I followed her through the streets and into a building at N.Y.U., and when she entered the exam room I slid up to the door and looked in. She was in a chair at the back of the room, still wearing her thin, brown leather winter coat with its tall collar standing higher than her ears. She was bent fearfully, huddled over the questions, her ballpoint pen clenched in a hand of white knuckles. She wrote very quickly and didn't stop until five minutes after the hour, when she had to surrender her exam to the professor. She came out of the room with a yellow, sickly face, looking killed. When she saw me, she came to me and said that she had been humiliated, had failed, it was my fault; but her voice was quiet and she seemed touched and very glad to find me waiting outside the room. I put my arm around her. She let me kiss her. We walked home together. Movies, the quintessence of excess, were becoming known as films—important to think about. Antonioni's movies were among the most important. Sylvia and I made sure never to miss one. We'd emerge feeling radically deadened, yet exhilarated, and sad that it had ended. She whispered once, as the lights came on, "Why can't they leave us alone?" It was terrible afterwards, having to thrust back into the windy streets, back to our apartment. We carried away visions of despair that had been exacerbated into gorgeous images. There could be thrills in tedium. Emptiness could be a way of life not only for Monica Vitti and Alain Delon but for us too. Why not? We'd read Nietzsche. Our brainiest and most promising friends—not only sad Agatha—brought regular news from the abyss.

Her exam was the best in the class. The professor encouraged her to persist in classical studies. She did not always do that well, but it was a miracle that she ever passed any exam. She took no pride in her success. Her acquisition of Latin and Greek had no special significance for her, and she never exhibited her learning in conversation or even referred to it. Academic powers and achievements were essentially meaningless to her.

"I'd give thirty points of my I.Q. for a shorter nose."

"Nothing is wrong with your nose."

"It's too long. A millimeter too long."

VIII

Sylvia's friend Agatha Seaman, who lived in Yonkers and visited us regularly, told Sylvia about a doctor in Switzerland who would reshape her nose without surgery, molding it by hand over a period of weeks, at his clinic in the Alps. Though Sylvia cared less about the shape of her nose than its length, she yearned for this mythical doctor. Not that she would go to him even if she could pay for his services, but she wanted to believe there was such a doctor, such hope for her nose. None of it sounded kosher to me, but I offered no opinions. Anyhow, I liked her nose, and I thought Agatha's doctor, like Agatha's life, was merely an expensive fantasy more relevant to her own problems than Sylvia's.

Agatha's problems focused strictly on boys. She was continuously subject to the most racking and degrading fixations on boys who were younger than she, very poor, ignorant, dark—Arab, Turk, Italian, Negro—sublimely handsome, seething with hatred of her, and vicious. This was her account every time. I never saw any of them.

She sprawled on our couch and talked to Sylvia for hours about the boys— how, last night, in a dirty, scary alley, she waited behind the hotel where Abdul or Francisco or Cesar worked as a bellhop, and, when he appeared after work, surprised him. The boys never called for her, never seemed to want to see her. They were sometimes outraged by these surprises, but she'd bring them gifts—sweaters, jewelry, leather jackets—tickets of admission to their lives. Trembling with humility, she would hold the gift forth until the boy looked, took it, relented.

She might have been a gift sufficient in herself—a slender bleached blonde about the same size and shape as Sylvia—but she indulged an enervated, unattractive manner; her voice, kept low and dull to suggest sensitive feminine reserve, suggested a low-voltage brain and morbidity; her complexion, embalmed for years in cosmetic chemicals, had the texture of tofu. Her hair was moon grass.

As she then followed the boy down the street, he'd fondle the gift, maybe try it on while Agatha whimpered about how beautiful he looked in it. Gradually his initial revulsion gave way to a different feeling, a species of desire, and he would lead Agatha into a doorway or phone booth, where he allowed her to blow him, or he'd root in her anal sphincter. Then he'd take off to meet his real date. "Mean, selfish bitch," said Agatha. In other words, if not for her...

A sort of contempt bound Sylvia to Agatha—maybe not unlike the boys— but Sylvia admitted to fascination as well. Beyond that, she simply liked her, as did I. In Agatha's sickly languid manner, in her air of fear and hurt, she had the appeal of dumb vulnerable things—doomed kittens, broken birds. Nobody could seem more harmless; she was even a little funny. She was also perversely exciting. The boys occasionally beat her up.

However obliquely—and despite our righteous anger at these boys and our sympathy for Agatha—it was impossible not to taste their nasty gratification and to suppose that, in her peculiar harmlessness, she invoked dark torturers. Simply being rich and pampered made Agatha potentially offensive; but then flaunting all that in luxurious gifts was to beg for cruel returns. Flaunting it also in our roach-infested apartment, in her stories, glorying in details of abomination as she lay on the couch, manifestly reborn, in the smartest frock from Madison Avenue. From there to Columbus Avenue and sleazy joints along upper Broadway wasn't a long walk. Besides, she had cab fare. She had plenty. Every new sensation was hers long before it was intimated as O.K. in Cosmo. Limp, colorless bit of a girl, she burned along the extremest cutting edge of avant-garde sensibility in the sixties. At last her mother had her committed to a Manhattan madhouse. Sylvia, astounded to hear that it cost several hundred dollars a day, felt twisted by envy and disgust.

We visited Agatha there. She sat in a neat, gray room with barred windows, high above the city, looking still softer and chastened into a new spirit of quiet composure. She named many celebrities who had stayed in this hospital, and she described young people among the inmates who struck her as marvelously interesting. What luck. She'd fallen, or been flung, into a crowd of sensitive kids. Artists, really, not lunatics. Her very kind. We'd gone to the hospital feeling sorry for her, a little frightened by what we'd see. We came away feeling annoyed and idiotic. She loved the place, was in no hurry to leave. She stayed for about five weeks.

IX

In those days, R. D. Laing sang praises to the condition of being nuts. French intellectuals were arguing for allegiance to Stalin and the Marquis de Sade. Diane Arbus was looking hard at freaks, searching maybe for a reservoir of innocence in this world. Lenny Bruce, at the Village Vanguard, a few blocks west of MacDougal Street, was doing hilarious self-immolating numbers. A few blocks east, at the Five Spot, Ornette Coleman was eviscerating jazz essence through a plastic raucous sax. In many salient forms of life and art, people exceeded themselves—or the self.

I'd come back from shopping, or doing the laundry—Sylvia never did these things, never once—and find Agatha in the apartment, lying about, telling all. I could hardly wait to hear it from Sylvia, stories about the wilderness of Manhattan where bodies descended nightly— rich, poor, white, black—fusing in the fevers of knowledge. When Agatha stayed very late, I'd walk her down into the street, then wait beside her for a cab. I worried for her. She might run into trouble—hapless, defenseless girl—alone in the dark. My heart, nourished long on latkes and gefilte fish, refused to acknowledge—despite her stories—that she was actually running after trouble in the dark. Sylvia's friend. Jewish. Chivalrous consideration was due.

"I'll take the subway, Lenny. It's too cold to wait out here.''

"No bother. I want to do it.''

Blinded by archaic, macho sentiments, the putz peered down the avenue, freezing, praying for a cab to appear and take Agatha away. Then he hurried back to Sylvia. Agatha had told her how a boy had forced her into prostitution a couple of times. The effect of this story is beyond my power to render.

Repeating the story to me, Sylvia was ironically amused and very appalled, posturing in her voice, mimicking Agatha's dull tones, as if to measure the distance between Agatha's lust for degradation and herself. I listened without ever feeling guilty about my pleasant interest in the sorrows of a friend. Actually, Sylvia's friend. Agatha never told the stories to me. Maybe that's why it seemed all right to be entertained by them. Besides, I imagined that Agatha was far gone—an object more than a subject—without profound claims on my feelings or influence on my life. She lay about for hours talking to Sylvia, but I owed her only politeness, a few minutes freezing in the street as we waited for a cab. My sympathy for her was easy. Liking her was also easy. Despite her affectations, corrosive cosmetics, intimidating clothes, and aura of self-destructive debauch, she was nonthreatening and even sort of cute. I liked myself for liking her. I didn't think, because Agatha could describe every bizarre peculiarity of her soul to Sylvia, in some mysterious way they were sisters. I didn't see, beneath the patina of contempt in Sylvia's retelling of Agatha's stories, that Sylvia was intimately involved in Agatha's fate. Then, one night in bed, Sylvia told me to call her names. "Call me whore, slut, cunt.

I was eventually to call her wife. Things would change then, I believed. But our fights had become so ugly and loud that the gay couple across the hall—who wouldn't say hello to us, though we passed frequently, almost touching, in the narrow dingy route to the toilet outside the apartment—began turning up their phonograph until it boomed above our shrieks. Always an eighteenth-century piece, wildly flourishing strings and a magnificent extravagance of golden trumpet—as if to insist upon the high, vigorous, joyous grandeur of civilization, and to shame us into silence.

They didn't like us. I assumed it wasn't merely because we made unpleasant noise, but also because of what they were—repressed midwestern types. Towheaded, hyperclean, quiet kids in flight from a small town in Ohio, probably Methodists, hiding in New York, where they could be lovers. It struck me as paradoxical that being gay didn't mean one couldn't be severely disapproving and intolerant. Personally, I loved eighteenth-century music. Couldn't they tell? Forgive a little? Weren't we all basically simpatico? They hurt my feelings, passing us in the hall with blank, rigid, ghostly faces, as if we belonged to an order of life beyond any recognition by them. Their soaring music damned us to oblivion. Their silence and their music threw me back on myself, embarrassed me, forced me to think Sylvia and I—not them, the gay kids from Molecule, Ohio—were marginal creatures; morally offensive; in very bad taste from the point of view of decent folks. They were right, but it seemed unfair. They didn't know. Perhaps I didn't either as I held Sylvia in my arms and looked into the black intelligence of her eyes, and called her names, and felt that I loved her, and said that, too. Didn't know we were lost. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now