Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowLate Bloomer

Fresh from raves at the Venice Biennale, British painter Howard Hodgkin is finally coming into his own with his first American tour, starting at the Phillips Collection, in Washington, D.C. JOHN McEWEN reports

JOHN McEWEN

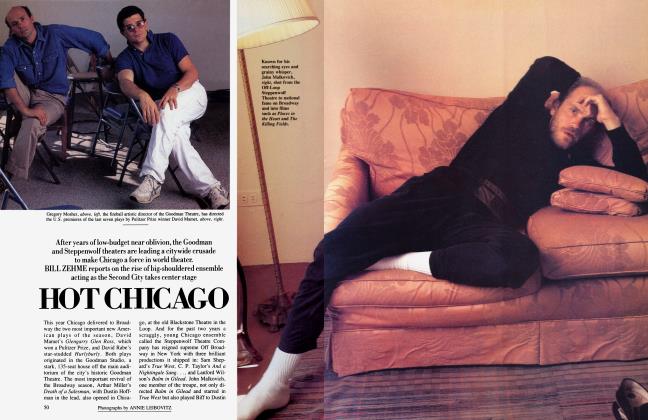

At the ripe old age of fifty-two, Howard Hodgkin finds himself the hottest property in English painting. His outstanding exhibition at this summer's Venice Biennale was both the people's and the critics' favorite, and now, following a string of successful solo shows in New York (the most recent at Knoedlerlast spring), his first American museum show (an expanded version of his Biennale retrospective) has begun a four-month tour of the United States at the Phillips Collection, in Washington.

This belated fame is all the more surprising when one learns that Hodgkin first determined to be an artist at age five, and paints in a style that is, if anything, a contradiction of the current fashion for size and energy at the expense of refinement and desirability. "Hodgkins" are often small, always considered and intended to be treasured domestic objects.

"I have always thought of pictures as 'things,' with as much physical character as tables and chairs or cups and saucers. At school I liked making pictures using very thick bits of cardboard covered in gesso, carving into the gesso, and adding color in the form of boot polish or whatever, to make it more of a 'thing.' "

Some areas of his paintings remain unchanged from the outset, but usually he revises and constantly overpaints, so the finished result represents an arduous accumulation of ideas. And yet the effort never shows, which is precisely the spontaneous effect he labors to achieve. Increasingly, this agonizing revision goes on in his head, giving his pictures an even more free and easy look, but the time and effort remain the same. It seems appropriate, therefore, that he makes things even harder for himself by painting on bits of wood that have an existing character to be overcome, rather than on anonymous panels or sheets of canvas.

Hodgkin's pictures, as far as he is concerned, are representational—but not in the conventional sense. They represent his feelings about people, rather than their physical appearance. Figures and objects are alluded to rather than described, with the inspiration being derived from one charged moment whose emotional significance is later— sometimes years later—the subject of a painting.

This method of slow development is consistent with the measured progress of his career, which began with his running away from some of England's most expensive schools, the sooner to get on with the job of being an artist. This eagerness, however, was balanced by a professional restraint that prevented him from showing solo in England till he was thirty and in America until he was forty. Like so many of the best English artists down the years, he is a stylistic loner, and his late recognition is the outcome of his own self-discipline rather than public neglect.

Certainly Hodgkin has never lacked for stimulus, at least of an environmental kind. Bom into a mainly scientific family—he can count the father of meteorology and the discoverer of Hodgkin's disease among his forebears— from the earliest age he had rooms and relations in plenty to fire his visual imagination. His cousin Marjorie Fry had a house full of bright decorations by her brother, Roger, the famous art critic, and other members of his Omega Workshops, and all the Hodgkins seem to have collected in one way or another, even if they did not admit to it. There was a great-grandfather who owned a copy of the Magna Carta and collected, among other things, cookbooks and books on fireworks; a grandfather with a roomful of delft tiles neatly catalogued on index cards; and his father, who worked for Imperial Chemicals but was obsessed by his scholarly garden of alpine plants. "Then there was my great-uncle Tolll—with three /'s. He lived in a flat, and when he could no longer move for objects, he simply took the flat above, and so on. When he died they found a Beethoven manuscript in one of the telephone directories. It was as mad as that."

Hodgkin calls this "the family disease" and readily admits to having contracted it as badly as most of his predecessors. He began collecting as a schoolboy and is today acknowledged as a leading authority on Mogul miniatures. In fact, ten years ago he was probably better known in the English art world as a collector and trustee of the Tate Gallery than as a painter, though for him there was no disparity.

"Collecting means a great deal to me. I don't know why people are so surprised, or seem to be, by my doing it, because so many artists have had collections. You remember the story of Picasso buying that incredible still life of oranges by Matisse? The price kept on going up and up and up and he couldn't understand why, though in the end he got it. And of course it had been Matisse who had been bidding against him."

The greater part of his collection of Indian miniatures is now on indefinite loan to the Victoria and Albert Museum, but, like all addicts, he is never so likely to be up to his old collecting tricks as when he says he has finally decided to kick the habit. In his Bloomsbury home, most markedly distinguished by a seemingly unique Italian Renaissance tondo of an African head, picked up on a weekend trip out of New York, there is usually some subtle change to show that the best is continuing to drive out the good, though never with the least hint of chichi contrivance. Chairs are in disarray, books lie on the floor, a desk top is a mess of mail, and the eau de Nil walls are, as he points out, no different in color from those of hospitals, town halls, airports, and police stations the world over.

Green is also something of an obsession with him. Hodgkin's country house is in as green an English valley as you could find. A mix of green carefully made to his own specifications and named "Long Dean" after this idyllic country retreat darkly differentiates the shutters and frames of his Bloomsbury house, and once adorned every suitable surface of the outside as well. In Venice the inside of the British Pavilion had to be totally repainted several times before the pitch of his specially requested pale green satisfied him (pale green being, in his opinion, the most light-absorbent and therefore sympathetic color against which to hang pictures), and some of his own most praised pictures in the show—The Moon, Clean Sheets, D.H. in Hollywood, In the Bay of Naples—are notably green, a comparatively unfashionable color in modem painting. When pressed, Hodgkin can trace its more personal and comforting associations to a memory of the color of the walls in his family home's dining room.

Hodgkin's childhood was beneficially disrupted—with regard to his artistic education—by the Second World War, when he became one of those well-to-do young English children sent off to America.

"Think how eclectic it all was! Here I was, aged nine or ten, learning all about French painting from looking at those marvelous pictures by Vuillard, Matisse, Leger, and so on in MoMA. It would have been impossible in England because people simply didn't collect them at the time."

His guardian was a family friend who lived in an extraordinary house on Long Island. She, too, seems to have been a crucial influence—an exotic person of great erudition, who took him to Quaker meetings (so reminding him, perhaps, of his Quaker origins) and collected as avidly as any of his relations back home. He particularly remembers a Queen Anne "Indo-Chinese" paper on the walls of her main stairs—canvas strips painted with flowers of red, orange, and brilliant green. This taste for Indian art was later stimulated by his art master at school in England, the art historian Wilfrid Blunt, who first opened Hodgkin's eyes to Indian miniatures.

Hodgkin himself later became an art-school teacher, but gave up twelve years ago when the demands of his own painting became all-consuming. He tries to visit India at least once a year, and divides the rest of his time among Wiltshire, London, and New York, where he now has the use of a loft.

"My professional life, however, is almost entirely in America. There are two or three people who will occasionally buy my pictures in England, but in New York all my shows have been very successful—and just the general acceptance and encouragement is stimulating. In America they understand that my pictures are representational, whereas in England they are puzzled and think they're abstract. In reality everything happens at once, and my painting tries to be realistic in this way. We can be breaking our heart and looking at the corner of the jukebox at the same time. All things are visually of equal importance— one emotion doesn't sweep it all away."

(Continued on page 121)

Continued from page 74

His London studio is white and unfussy, not an enlarged and three-dimensional "Hodgkin," like his two-part living room upstairs. No extraneous ornament hangs on the wall except a tambourine hitched to a nail, presented by the painter Patrick Caulfield for Hodgkin to beat the daylights out of when things go wrong. Stacked on the floor are the stubbornly individual bits of wood—trays, blackboards, breadboards, filled-in picture frames—that will be recycled into new life as paintings. As many as twenty may be in the works at any one time, some taking months and even years to finish, thanks to Hodgkin's agonizing need to constantly revise.

"My Quaker heritage is inescapable. I remember being extremely pleased when somebody said about my collecting, 'Oh, Howard's very strict, very severe with himself,' meaning that if I felt something was bad I wouldn't keep it on grounds of sentiment. It also partly explains why it took me so long to learn how to be a painter. ' '

It is on this point that he finds the example of Matisse so inspiring.

"Matisse, I think, gave a great many people a feeling of moral courage, but he also showed how an artist today has got to be his own patron and his own audience and often his own dealer and his own critic. And that is a rather uncomfortable position to be in. The ideal life of an artist would certainly not be one in the twentieth century, but that's beside the point. As for the rest, someone years ago asked what my paintings were for. I said they were for hanging over a mantelpiece or a sofa, and I still don't think that's putting them down for a second. It's to do with paintings' being part of life as it's lived all the time. However large they may have become, they're meant to be from me to you."

Hodgkin's pictures can be on a more ambitious scale these days—like the strikingly explicit but nevertheless daringly spare Interior with Figures. They may still autobiographically depict specific events and places (like David Hockney [D.H. in Hollywood]), but today Hodgkin's paintings are concerned more with his own life than with the wittily interpreted lives of his friends. They are technically more lush, sexier, and psychologically more complex.

Such newfound freedom of expression and the latest wave of success, however, leave him characteristically unsatisfied.

"I want to be a better, more intense artist. And I'd like to be rich and famous too, but only for a moment, to see what it's like. I think of this year as the beginning of my life as an artist, rather than any peak. Up till now it's been 'fifty years of foreplay,' as I'm accused of saying." □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now