Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTELEVISION

Washington Talk and the Gang of Five

James Wolcott

Like a bookie parlor, Washington, D.C., is a hive of hot tips and sudden hunches. It's a town with a telephone stuck to its car, measuring out its life in message units. Not only is Washington wired into itself, abuzz with news and feedback and loose conjecture, it's wired into the nation at large through such public-affairs shows as Washington Week in Review, This Week with David Brinkley, and The MacNeill Lehrer Newshour. Although Sam Donaldson loves to misbehave on ABC's This Week (he's as incorrigible a terror as Red Skelton's "mean widdle kid"), the tone of these shows is wry, respectful, in the know. Tempers are kept in check, and issues are discussed without a severe ideological tilt. On Washington Week in Review the reporters are so cautious about appearing fair and above the fray that their observations seem cushioned with layers of down. Washingtonians themselves have no need or desire for such insulation—they want the wind raw in their hair. So they prefer a program like Agronsky & Company or its upstart rival. The McLaughlin Group, both of which arc broadcast on Saturday evenings in Washington, enabling political junkies to enjoy a double injection.

A longtime Washington favorite, Agronsky & Company is moderated by Martin Agronsky, a liberal veteran who uses his wise, patient hands as if he were weaving the very fabric of democracy. The show's run of glory was during the Watergate era, when each week brought a fresh catch of scandal for his regulars to weigh and scale. However, the thumping shock of Reagan's triumph has left Agronsky woozy, floored, and a bit put out, the fabric of democracy limp in his defeated hands. "We are in a fnist, and cannot know ourselves" became the show's refrain. Such a familiar refrain, in fact, that in 1981 Michael Kinsley's brilliant parody of the show in The New Republic had Hugh Sidewall (Time's Hugh Sidey) dithering on so wordily that the Agronsky character finally became testy:

JERKOFSKY: ...Well, tell me this, Hugh. If, as you seem to suggest, you know nothing about anything, why do I pay you to drone on week after week on my show?

SIDEWALL: Well, you know, Marvin, that's a very good question, and it's one I've heard being asked at the very highest reaches of government in my major lunches around Washington and in traveling across the entire country. But there are no conclusions at this point, and we'll just have to wait and see. It's hard to say. No one knows for sure....

JERKOFSKY: Hugh, do you have any brains left at all?

SIDEWALL: I don't know, Marvin. We just can't say.

Earlier this year there was a major change in the Agronsky & Company roster which has served only to make the show even more vague and irritable. George Will, after long service, cleaned out his kitty in order to manicure his ironies full-time for ABC. (Agronsky is syndicated nationally.) With Will gone, the angel wings of sweet reason were pinned on The New Yorker's Elizabeth Drew, who has hardly worn them with flying bravura. Like Hugh Sidey, Drew is a member of the there-are-no-easyanswers school of discourse, though she tends to favor the royal "we." (Eliza beth, how would the nation react if a big hairy monster ate the president? "We don't know, Martin, we just don't know.") But Drew has added a drop of acid to the show's chemistry by being a real dill pickle on etiquette, a Miss Manners without charm. "If! may fin ish my thought, Hugh ..."" As I was saying before 1 was interrupted, Mar tin..." She's always having her rich thoughts interrupted, poor thing! And always reminding us of the rich though she had weeks before. "Martin, if you will recall, I said two weeks ago on this show that..." Perhaps the supreme expression of Drew's above-it-all snootiness came when Agronsky asked the group for its reactions to the summer games and Drew replied with a triumphant smirk, "I haven't been watching the Olympics." I wanted to bop her one.

(Continued on page 97)

(Continued from page 95)

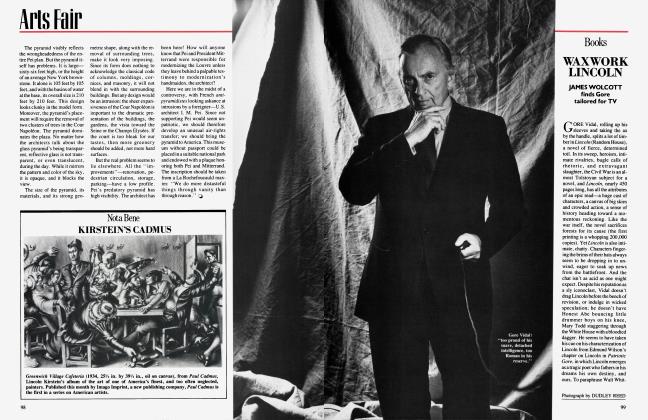

When George Will said farewell on Agronsky & Company, he saluted the show's "conspicuous civility," which may have been a subtle dig at The McLaughlin Group. For civility is what is conspicuously missing from The McLaughlin Group, where the air is peppered with buckshot. If Agronsky & Company mirrors liberalism's current mood of funk and disarray. The McLaughlin Group represents Reaganaut conservatism in all its bare-knuckle confidence and might. The group has even given itself a fighting nickname: the Gang of Five. The Gang of Five comprises Morton Kondracke, executive editor of The New Republic; Jack Germond, a syndicated columnist based at the Baltimore Evening Sun; Patrick Buchanan, a syndicated columnist and former spear-carrier for Richard Nixon; Robert Novak, of the infamous syndicated-columnist duo Evans and Novak (or "Errors and No-facts," as their critics have snickered); and the host, John McLaughlin, a former Jesuit who served under Presidents Nixon and Ford and currently publishes a column on the Washington scene in the National Review, where every day has a red dawn.

Unlike Agronsky, who's content to set his topics into motion and then gently coast, McLaughlin is always at the wild center of his big-top circus. He's the show's tower of power, its smokestack of indignation, its mad mullah. He uses his hanging-judge voice as a gavel, rapping the show to disorder and demanding a strict verdict: "On November 6, will Geraldine Ferraro be a plus or minus for the Democratic ticket?" And if a guest waffles, he booms in capital letters: "PLUS or MINUS?" Big John don't allow no choirboy mumblin' around here.

In an interview, McLaughlin told me that he considers issues to be "living entities" that come and go, thrive and wither, hibernate and have to be roused from hiding. So his abrupt queries are a way of shaking the possums loose from the trees and seeing where they skedaddle. With issues like Lebanon, the economy, and Central America, it's more important, says McLaughlin, to get "the right spin" on a week's topics than to try to be exhaustive. It's also, he acknowledges, a way of separating the men from the boys—which here means the conservatives from the liberals. To McLaughlin, conservatives are creatures of flinty convictions who, when duty calls, "grab the musket from the wall." Liberals, by comparison, are political adolescents who muddle Hamletlike across a darkened stage in tights, pale-cheek'd and indecisive. On The McLaughlin Group, Mort Kondracke has been cast as the boychik Hamlet, whose evasive answers allow McLaughlin an opportunity to "philosophize on the liberal epistemology." But in truth McLaughlin doesn't indulge in much philosophizing; mostly he just barks and tells Mort to finish his oatmeal. Confronted with the real Hamlet, McLaughlin would demand to know, "Regicide—is it a plus or minus for Denmark?" Doubt and introspection drive him batty. But it's an entertaining battiness, with a tail-tale air of self-parody. There's something big and rumpled and foolish about McLaughlin's bluster—he reminds one of John Wayne in his late phase, going merrily to seed in True Grit. McLaughlin is a more dapper presence (I can't quite see him slopping off beer foam with his sleeve), but he too seems to enjoy gunfire and a hearty gallop. His regulars ride behind him like a posse, yelling "Whoa!" What makes the show itself entertaining— and, for all its exasperations, it is the most entertaining talk show on television today—is this sense of bickering camaraderie. The Gang of Five have even begun to speak in their own rootin'-tootin' rhythms. On one program, McLaughlin showed a clip from a Republican ad depicting Tip O'Neill as a bloated despot and canvassed his guests for their responses. "Stinko," said Robert Novak. "Ditto," said Jack Germond. "Zip," said Mort Kondracke. "I give it a zip, too," concluded McLaughlin. And when Novak charged that Jesse Jackson was the advocate of "tinhorn totalitarian Third World bozos," McLaughlin remarked, "Are those bozos doing a rope-a-dope?— that's what I want to know." In exchanges this clipped and coded, The McLaughlin Group takes on the crackle and inner dynamics of a George V. Higgins novel, or Glengarry Glen Ross. It's a world without women or minorities— a world of white men dishing up the spoils.

The McLaughlin Group has been criticized for being in essence a brotherhood of the honkie elite.

This men's-club chumminess hasn't gone unremarked. Although black and women reporters have been allowed to saddle up for Big John's posse (Eleanor Clift of Newsweek is an occasional backup guest, and Chuck Stone of the Philadelphia Daily News appeared on the pilot episodes, later telling the Washington Weekly, "I was the token shvartser"). The McLaughlin Group has been criticized for being in essence a brotherhood of the honkie elite. Indeed, I detected a note of self-directed criticism when Jack Germond described the Republican convention as a deathly boring gathering of "smug white folks who said, 'If you adopt our line, you can become rich and white like us, and put down other people' "—not an inapt way to encapsulate the mind-set of the show's conservatives. McLaughlin not only is unapologetic about his whiteguy bias but delights in being provocative. When Mondale picked Geraldine Ferraro for his running mate, McLaughlin announced, "It's a girl." A few weeks later he opened a segment on Ferraro's financial problems and the effect these would have on the Mondale effort with a bit of advice from My Fair Lady: Never let a woman in your life.

No, racial/sexual integration of the Gang is not topmost in McLaughlin's mind; he's more concerned with the political mix of the show. McLaughlin prefers hard, opposed clarities to wishywashy syntheses—he feeds more happily on the hard-left polemics of The Nation than on the soft-left polemics of The New Republic. Even though Mort Kondracke has been typecast as the show's starry-eyed liberal, he is in fact a pragmatic moderate who's gravitated so far to the center that he even flirted with an endorsement of President Reagan in an article published in the Wall Street Journal—a musing that did not make all of his colleagues at The New Republic brim with glee. (When T.N.R.'s Michael Kinsley was asked on radio whether or not Kondracke would vote for Reagan, Kinsley replied, "He better not.") To McLaughlin, Kondracke is a transitional figure on a "quest" for fundamental values. But if that quest takes Kondracke too far right, McLaughlin will have to round up a new lefty to give him apoplexy.

For the time being, however, the Gang of Five is intact and The McLaughlin Group has found its moment. With its fast chat, inside savvy, and judo chops of emphasis, The McLaughlin Group is the perfect locker-room show for Reaganauts tired and exhilarated after a busy week of bashing liberals. Although The McLaughlin Group runs second to Agronsky & Company in the Washington ratings, it's syndicated to more than 130 stations nationwide, and could ride the crest of a second Reagan term, leaving Agronsky paddling behind. The question is how well the show will wear. It is already dangerously close to shtick, as each week Novak coyly bats his almond eyes and tells one and all how uninformed they are, and McLaughlin smokes the floor with hostile, withering glares. Will Mort Kondracke inch further toward the infernal right? Will The McLaughlin Group unseat Agronsky & Company as the local Washington favorite? Can Sally and Catlin find true love on Another Worldl In the immortal words of Elizabeth Drew, "We don't know, Martin, we just don't know." □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now