Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

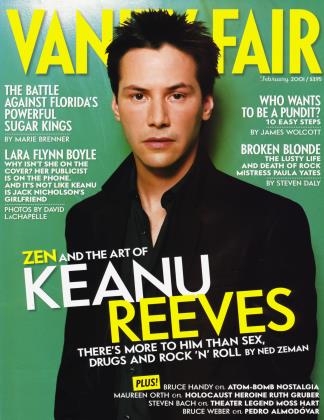

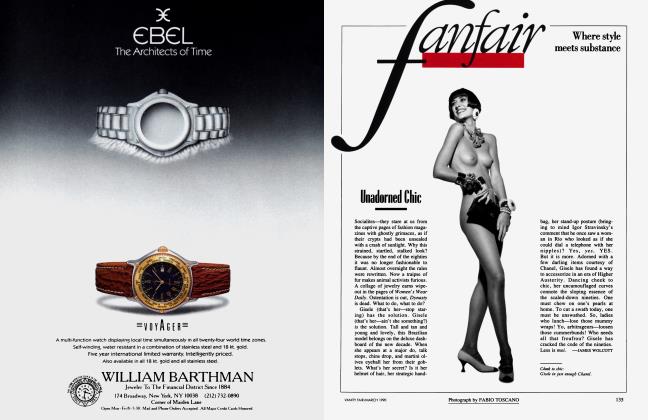

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowPUNDITRY FOR DUMMIES

JAMES WOLCOTT

Why sweat over your laptop, trying to make every word count, when you can gasbag your way to fame and lecture fees? TV punditry looks easy (and it is), but for lasting success-a la Chris Matthews, Jeff Greenfield or Margaret Carlson-follow these 10 simple rules

Nothing puts more of a damper on a writer’s day than actually having to drop anchor and write. Civilians think a writer’s life is taking sips of coffee in your bathrobe while the rest of the world reports for work, but from the writer’s perspective it’s more like being in perpetual summer school, stuck indoors while everyone else is out playing. All of the time-honored delay tactics and sorry excuses for missed deadlines handed down through generations of hacks—from the coffeehouse wits of 18th-century London to the Josh Freelantzovitzes of our own day, bent over their laptops in the window seats at Starbucks—only postpone the inevitable anticlimax of having to put away the newspaper, mute the TV, and coax a few dinky paragraphs out of one’s inner blah. Nonfiction writers have discovered that there is a lucrative way to lighten this overhanging chore. It’s called punditry, taken from the Hindi term for a “learned man,” and it can be the ticket out of the tedium of trying to make every word count. Once one can parlay a byline into a TV I.D.-tag, the quality craftwork of journalism-constructing paragraphs as if they were fine cabinets, filigreeing the sentences with a wry touch here, a bass note there— becomes a Victorian enterprise that no longer need weigh one down. Being granted the license to blab on TV permits the writer to blab in print, since it all becomes part of the same shtick. Grooming a loftier persona on the page will only confuse your new fans! Now that so many journalists are hanging out their shingles on the Internet (Mickey Kaus, Andrew Sullivan, and Joshua Micah Marshall all have their own busy Web sites), the old Walter Lippmann formalities have gone kaput. Chat is king.

Sure, punditry looks easy, doubters will scoff. Because it is! Do you think Tweety Birds such as Margaret Carlson (Time) or Tucker Carlson (no relation, The Weekly Standard) could do it if it weren’t? Moreover, job prospects have never been riper. Everyone grouches about tracking polls, photo ops, and “Sabbath gasbags” (Calvin Trillin’s pungent phrase) to equally futile effect: the expansion of cable news coverage of the latest hoo-ha—what Frank Rich has christened the “Mediathon”—requires a full roster of rotating faces, some fresh, others old-reliable. (The cable channels often stack four pundits at once in a Brady Bunch grid.) But if instant analysis seems like an E-ZPass lane to fame, highway-robbery speaking fees, and unctuous phone calls from senior officials close to the president, beware. The spiral staircase of punditry is strewn with the twisted remains of writers who couldn’t quite make the climb to the top. Scant years ago, Ruth Conniff of The Progressive surfaced on CNN talk shows, so young, so full of peppy, socialist idealism. She’s supposedly a regular commentator on the Fox News Channel, but I didn’t spot her once during the electioncrisis coverage—where were they hiding this breath of spring? Where is sourpuss Washington Times columnist Mona Charen, a once familiar presence? Her conservative parking spot seems to have been delegated to Kate O’Beirne of the National Review (a regular on CNN’s The Capital Gang), leaving Charen in limbo. Of the blonde-witch coven that boiled Clinton in a pot over Monica Lewinsky, Laura Ingraham (author of The Hillary Trap) is still making the rounds while Ann Coulter (author of High Crimes and Misdemeanors: The Case Against Bill Clinton) seems to have fallen by the wayside, no longer enticing viewers with the Basic Instinct ride of her miniskirts and Fatal Attraction stare.

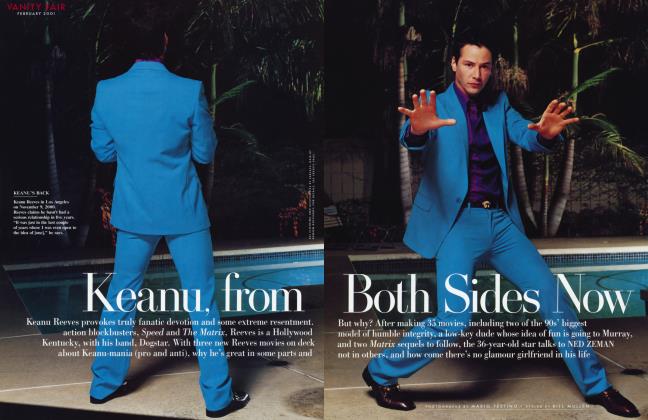

The Gap-ad attire of Andrew Sullivan telegraphs a nonconformist message.

To assist my brethren in their ruthless climb to the hospitality suite of celebrity journalism, I have devised a 10-point program that will help prospective pundits not only get to the top, but stay there.

I. ABANDON YOUR IDEALS

They’re only holding you back. You’ll feel so much better, so much lighter, once you let go. There was a time when your role model might have been Bobby Kennedy in rolled-up shirtsleeves wading into a sea of outstretched hands in Harlem; or perhaps—shudder—it was Newt Gingrich standing like the Pillsbury Doughboy before the billboard-size copy of the Contract with America on the steps of the Capitol. Treasure these images in your scrapbook for their inspirational value, but don’t let them mist your mind. To be a successful pundit is to forgo quixotic crusades for a hard-boiled cynicism and sarcasm worthy of a film noir detective in some fancy joint. Henceforth, you must patronize politicians (aside from a few personal pets) as used-car salesmen, dismiss civil servants as “faceless bureaucrats,” and regard foreign partners as America’s puny chess pieces. Consider Chris Matthews, host of MSNBC’s Hardball, and Lawrence O’Donnell Jr., MSNBC’s senior political analyst and a panelist on The McLaughlin Group: Matthews worked for former House Speaker Tip O’Neill, O’Donnell for Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, yet you’ll seldom hear them crooning about the glory days of Democratic liberalism, mourning the loss of sweeping social initiatives. They see through their former allies and cronies, saving their most fire-breathing scorn for liberals who pad their ambitions in soft, pandering baby fat. Their favorite target is Bill Clinton, who symbolizes the damp underbelly of the Kennedy legacy of public jauntiness, private debauchery. They beat up on him like a couple of rogue cops. (The liberal pundit who has kept the faith is Doris Kearns Goodwin, wrapping her rooting interest for a return to New Deal/Great Society big-government rollout in warm nostalgia.) On the Republican side, Tony Blankley, Gingrich’s former mouthpiece and also a panelist on The McLaughlin Group, can barely recite the conservative mantra of less regulation, lower taxes without his lips betraying a smile. He dresses like a dapper riverboat gambler, as if to signal to the audience, “Don’t kid yourself, folks—it’s all a game.”

2. DRESS THE PART

Tony Blankley can get away with a Jackie Gleason ensemble—a portly dandy can carry off a carnation in the lapel. You, buster, probably can’t. The moody Mafia hit-man dark shirts and electric ties of Salon’s Jake Tapper are a singular statement, as is the casual Gap-ad attire of Andrew Sullivan, which telegraphs a nonconformist message consonant with his gay-Catholic-conservative identity. (Michael Kinsley in the same outfit would look as if he forgot to change.) One fashion option is the popular bow tie. The pre-eminent bow-tie pundit is, of course, George Will (ABC’s This Week with Sam Donaldson and Cokie Roberts), on whom this puckish accessory achieves an odd sobriety. It seems to fasten his gravitas in place. On Thomas Oliphant (The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer) and Tucker Carlson (the rising star of CNN’s Late Edition and The Spin Room), it serves a more traditional function as a twerp accessory. But for most male pundits, standard business attire is the safest bet.

Female pundits such as Margaret Carlson employ Susie Student eyeglasses for that sorority look, but most choose a sedate, borderline-matronly wardrobe and a coif that might be called Hillary lite. The balancing act for women is looking attractively telegenic without coming on too overtly sexy, arousing the resentment of other women and impure thoughts in the horny hosts (a mistake made by Ruth Shalit, who, before she gave up political reporting for advertising, appeared on Politically Incorrect with Bill Maher in dome shoes and baby-doll makeup). Sparky blondes such as Laura Ingraham, who posed on the cover of The New York Times Magazine in a leopard-print miniskirt, have learned to lower their wattage and adopt a tamer junior-law-partner getup that makes their political cheap shots sound like feisty advocacy.

3.BURY YOUR NOSE IN DON IMUS

The view isn’t pretty, but it’ll pay off down the line.

The successful pundit understands that punditry begins at dawn, with a quick on-line skim of the buzzworthiest sites (Drudge, Salon, Slate) and a mental download of the New York Times op-ed page to find out the smarty-pants line to take as laid down by Gail Collins or Maureen Dowd. Then it’s time to tune into Imus in the Morning, a syndicated radio show simulcast on MSNBC, the breakfast club of the punditry. Although Imus has lost audience share in recent years, his appeal to the Northeast Corridor media elite has never been stronger. The I-man stamp of grumpy approval (“Bernie, see if you can get that lying weasel Paul Begala on the phone”) means that the pundit has well and truly arrived. Tim Russert, Jeff Greenfield, Laura Ingraham, Jonathan Alter, Howard Fineman, Frank Rich, Chris Matthews, Cokie Roberts, Mary Matalin, Mike Barnicle, George Stephanopoulos, Bob Schieffer, even the reclusive Maureen Dowd—all take their spin at the mike as members of the Imus all-star squad. To make it onto the Imus show, however, his people must call you. Being pushy will only earn you Imus’s leather-tongued wrath. While waiting for this summons to the majors, familiarize yourself with every aspect of his big-deal life. His bossy wife, Deirdre. His son, Wyatt. His ramshackle brother, Fred. Become conversant on I-man topics such as Joseph Abboud neckwear and custommade cowboy boots; listen to Delbert McClinton, read Kinky Friedman mysteries, catch Rob Bartlett in the play Tabletop. Prepare yourself, grasshopper, for the trial ahead, always keeping in mind the message of hope enunciated by Johnny Carson, who, after a particularly obsequious compliment from sidekick Ed McMahon, turned to the camera and pronounced, “Sucking up does work.”

Imus's stamp of grumpy approval means that the pundit has truly arrived.

The danger of dealing with Imus is sucking up to excess. Even the most vain monarch doesn’t want his courtiers to drool. An Imus rookie must be a dignified toady, making exaggerated bows to his exalted status (“Yes, Your Lordship, the Dixie Chicks indeed rock”), extracting from his incoherent ramblings a pithy nugget of received wisdom, and accepting his teasing as part of the hazing process. Once you’ve passed the Imus initiation, proceed carefully. Don’t get too chummy. Work in the fawning references to Deirdre, Wyatt, and the Imus Ranch slowly, judiciously, raising yourself from a prostrate position by imperceptible degrees. A sudden swagger will only provoke Imus to pop open a can of salsaflavored whupass. I-man regulars such as CNN’s Jeff Greenfield and radio host Mike Francesca enjoy the privilege of flinging darts at Imus’s expense, targeting his temper and turkey neck, but insult humor from a relative newcomer is a risky proposition. Err on the side of caution. Above all, never presume to call him “Don,” an honor reserved for media equals (Russert, Tom Brokaw) and longtime pals (sportswriter Mike Lupica). The deference you pay will yield lifelong dividends. Because once you’re inducted into the Imus fraternity, you’re set. The Cosa Nostra couldn’t be tighter.

Consider the case of columnist Mike Barnicle. Accused of plagiarism and fictionalizing sources, this stale-beer, manof-the-people Mike Royko pretender was bounced from The Boston Globe and could have easily joined fellow miscreants Janet Cook and Stephen Glass in journalism’s leper colony. Almost anyone else would have had to slink off into anonymity. But braced by Imus and Tim Russert, who kept throwing him on the air despite the leaky holes in his reputation, Barnicle managed to win back his badge and completely recharge his blowhard batteries. He has a new soapbox in New York’s Sunday Daily News and has survived his own perfect storm. So take heart: pundits are loyal to their own kind, once they make the cut.

4.MASTER THE SNAPPY PATTER OF POP CULTURE

Many of the eulogies for Lars-Erik Nelson, the Daily News columnist and New York Review of Books contributor, whose death in November left an unfillable gap of candor and integrity, quoted a complaint he had lodged against his colleagues in the press—that what they were practicing these days wasn’t political analysis but “theater criticism.” Shrewd owls such as Nelson and Jack Germond represent a diminishing breed. In the past a prospective pundit could pass inspection by mouthing a rosary of political cliches. The New Hampshire primary: “retail politics.” Social Security: “the third rail of American politics.” Ronald Reagan: “the Great Communicator.” Today’s pundit, raised in front of the TV and the computer screen, doesn’t have the luxury of dismissing political theatrics as so much mascara. She or he has to be not merely a theater critic but an insatiable pop-culture sponge, putting an Entertainment Weekly face on every political player (Katherine Harris as Cruella De Vil). It is not enough to trot out the same tired line from Casablanca (“The Republicans were shocked, shocked, to discover pork in the House appropriations bill”), or to evoke Wayne’s World (“It looks as if Ralph Nader will be forgiven by the DemOCRATS-NOT”). Keeping tabs on current pop-culture fluff is hard work, requiring constant scanning, a cement butt, and the ability to turn attention deficit to your advantage. Let Maureen Dowd be your Love Boat guide. She and New York Times colleague Frank Rich are the ones most responsible for chasing politics through the cineplex. A recent Dowd column on George W. Bush began, “President-elect (?) MiniMe has not yet started gnawing on his cat, as the Austin Powers’ Mini-Me did to the hairless Mr. Bigglesworth”—a wisecrack that was cited that week by A1 Hunt on The Capital Gang, much to Robert Novak’s unamusement.

5.PICK A SIDE, THEN STICK WITH IT

Crucial to the career prospects of the aspiring pundit is deciding which team to play on. Committing to conservatism based on a close reading of Edmund Burke, the Federalist Papers, and the criticism of T. S. Eliot has become as passe as subscribing to liberalism after repeated exposure to John Stuart Mill and Arthur Schlesinger Jr.’s The Age of Roosevelt. Unless you’ve undergone strict Jesuit training, having too much intellectual ballast will only load you down and hamper your agility to dance around the truth when it comes time to defend Tom DeLay without gagging. No, today one’s political loyalty is mostly a brand preference, like choosing Coke over Pepsi, Apple over Wintel. (Or a negative brand-selection rooted in antipathy, a way of signing up for any posse hounding Hillary Clinton.) Once your political label is chosen, however, it’s pinned to your hide. Idiosyncratic political commentators who attack issues from unpredictable angles, such as the brilliant Kevin Phillips, who went from crafting Nixon’s southern strategy to being the pin-striped populist of the books Arrogant Capital and Boiling Point, perplex talk-show programmers trying to book a simple Punch-and-Judy act. Similarly, sage elders who transcend partisan bickering, such as The Washington Post’s David S. Broder, the anointed egghead of Washington correspondents, function as sedatives during periods of national uncertainty and unrest. As long as Broder retains the title of the press corps’s most respected calmer-downer, no one else need apply. Your task is not to hold complex problems up to a prism or to allay the anxiety of a troubled nation; your job is to dig a foxhole on one side of the liberal-conservative divide and fight like a breezy fanatic, giving no ground.

Margaret Carlson employs Susie Student eyeglasses for that sorority look.

But which side? Eight years of Clinton scandal and the insurgence of Fox News have created openings for conservative nasties, but the saturation level may have been reached. Radio gripefests are dominated almost entirely by filibustering reactionaries like Sean Hannity and Bill O’Reilly (both Fox hosts). Unadulterated liberals have become so rare that the stars of Fox’s The Beltway Boys, Mort Kondracke and Fred Barnes, are forced to collude in the laughable fiction that a lukewarm moderate like Kondracke consorts like a French hussy with the left. (When not crossing his arms and pouting, Fred makes ho-ho references to Mort’s “liberal buddies on the Hill.”) If I were you, I’d seize the opportunity of a possible liberal swingback and try out for the underdog team. Unless, of course, you feel that would violate your “principles.”

6. ONCE YOU STAKE OUT A POSITION, FEEL FREE TO ABANDON IT

Dramatic flip-flops, which can be fatal to the health of a political career (“Read my lips—no second term”), are integral items in a pundit’s acrobatic repertoire, along with the Palestinian-state pommel-horse straddle, the whoopee cartwheel, and the indignant whipback. Logical inconsistencies—lauding Anita Hill as a brave voice speaking truth to power, then diagnosing Kathleen Willey as a hysteric; asserting “the rule of law” until the rule of law rules against you—can be tucked into the larger consistency of sticking to the game plan. Twenty-twenty hindsight and a dose of amnesia allow even the most myopic opinion-maker to smooth out bad calls into the clean horizon of history. (Pundits who pronounced Clinton “political dead meat” during the Monica craze now marvel at his Houdini escape as if it were an outcome any fool could have foreseen.) Maintaining a fluid line of logical inconsistency means that the old debatingsociety rules no longer apply. In the early years of Firing Line, which was broadcast from 1966 to 1999, host William F. Buckley Jr. had a feline ability to tease out the weak threads of an opponent’s presentation until the entire case seemed to unravel. Today no one has the TV patience for such slow, methodical cross-exams. Constant interruptions and high-contrast personalities have miniaturized political debates into karate catfights, midair duels of catchphrases.

He/She says, “Chinese money-laundering!” You say, “Iran-contra!”

He/She says, “‘No controlling legal authority!”’

You say, “‘Subliminable!’”

He/She says, “Class warfare!”

You say, “Top 1 percent!”

In the future, the transcripts of pundit squabbles will come to resemble snippets from e. e. cummings, chunks of concrete poetry.

doorpound of miami mob!

dimpled ballot bingo. Katherine Harris’s red-red lipstick —democracy’s deathkiss gore (sigh)/bush ... hidebehinddaddy How dja lk yr willofthepeople

now?

mr chad

7. LEARN TO MODULATE

Each pundit must turn himself into a one-man or -woman rapid-response machine, a compact version of the ClintonGore model. But the necessity to speak fast doesn’t entail the necessity to speak LOUD. A pundit can raise his voice on occasion as long as it doesn’t become a persistent foghorn.

The decline of John McLaughlin is instructive. A former speechwriter and special assistant to Presidents Nixon and Ford and an editor and columnist for the National Review, McLaughlin launched The McLaughlin Group in 1982. From the outset his band of pundits—which included the Prince of Darkness, Robert Novak—buffaloed through the modest compunctions and courtesies that characterized stodgier public-affairs shows such as Washington Week in Review and Agronsky & Company (whose verbal footdragging was hilariously lampooned by Michael Kinsley in The New Republic). McLaughlin redefined the genre, and the panel itself took their act on the road, playing corporate events. The group’s recognition factor peaked when Saturday Night Live parodied the show, with Dana Carvey imitating McLaughlin’s stentorian boom and gavel-rapping verdicts (“Wrong!”), asking absurd round-robin questions, and ringing innumerable bananafana changes on Kondracke’s name (“Mort-on Salt, when-it-rains-it-pours ... what say you? ... Wrong/”). McLaughlin took the wrong lesson from the satire. He seemed to believe that the skit’s whopping success signified that audiences found his excesses endearing: he became even more of a caricature after Carvey’s send-up, as if to show he was in on the joke and, what’s more, could top it. For a man already riddled with hubris, priding himself as a mirth-maker was the folly of follies. As the show grew into a franchise, The McLaughlin Group began to drown in its host’s chicken fat. McLaughlin’s introductions became longer and fuller of thunderation, his choice of topics even more arbitrary and capricious; he imperiously played musical chairs with the panelists, antagonizing Novak and Germond until they finally defected. In Germond’s memoir, Fat Man in a Middle Seat, he recalls how McLaughlin assumed the airs of a selfappointed caesar in the studio and on the road, hogging the money and sliding into a chauffeured limo while the other panelists had to pile into a van. His top-heavy ego eventually took its toll. In recent years, ratings for The McLaughlin Group have sunk like a damaged submarine, McLaughlin himself becoming a rusty relic, a dull roar.

To be a pundit is to forgo quixotic crusades for a hard-boiled cynicism.

His mouth has been supplanted by Chris Matthews’s on Hardball. It’s Matthews who is now the alpha-male master at talking over his guests, tackling their responses in mid-sentence, and freeassociating like Dutch Schultz on his deathbed. But Matthews may have heeded the warning of McLaughlin’s meltdown. In November, Saturday Night Live did a parody of him, mocking his outboard-motor manner and compulsion to ratchet up every discussion into a screaming meemie. Unlike McLaughlin, Matthews didn’t interpret the parody as a popular mandate. It seems to have chastened him. Since then he’s toned down his demeanor, becoming a reasonable facsimile of a rational person. On Charlie Rose recently, he seemed almost ... calm. If he can continue to adapt, he’ll be able to dodge the nickname of “Old Yeller.”

8. DON'T MERELY GIVE ADVICEHELP GUM UP THE WORKS!

“I can speak to almost anything with a lot of authority,” Fred Barnes is quoted as saying with fathead complacency in Eric Alterman’s Sound and Fury: The Making of the Punditocracy. Speaking with authority on everything from global warming to the ripple effects of Viagra is vital to a pundit’s aura of offhand infallibility. A pundit is someone who knows exactly how hard Alan Greenspan should tap on the brakes to glide the economy to a soft landing, what the price of gas should be at the pump, where and how NATO forces should be stationed, and whether Microsoft should be compelled to unbundle its browser. You’ll never hear a pundit confess, “Man, the Mideast, what a mess—glad it’s not my problem.” But sometimes it isn’t enough to be a nimble know-it-all. Crucial moments in the course of human events require a more active meddling.

On Election Night, NBC and Newsweek’s Jonathan Alter boldly stepped forward to help ball everything up. Only a week and a half earlier, Alter had told viewers of the Today show, “As many Americans know, the person with the most votes doesn’t necessarily win. The election is decided by the electoral college.” But on Election Night he flabbergasted Tom Brokaw (not an easy thing to do) and Tim Russert at the anchor desk by contending, “If it turns out that A1 Gore wins the popular vote nationally, there will be intense pressure in this country to have him become the president. Most people think the guy with the most votes wins. The political pressure would mount quickly to certify A1 Gore as the winner.” Whoa! cried Brokaw and Russert, quickly dismissing this scenario and reasserting the primacy of the electoral college. “Yet in that moment, as his seniors smacked him down,” wrote John J. Miller in the National Review, “Alter laid out what has become Gore’s postelection strategy: denigrating an outcome in which Bush wins by the rules but not by a popular vote. Alter was on-message, even before there was a message to be on.” And thus served as the advance scout guiding the Gore mule team and the electoral process into the Florida swamps and the morass of multiple lawsuits and political stalemate.

Way to go, guy!

9. INSULATE YOURSELF FROM "THE LITTLE PEOPLE"

Sometimes, sadly, to make new friends you must leave old friends behind. To become a successful pundit means saying good-bye to all “the little people” you used to know, those superfluous souls who aren’t on TV and fill in the space in the fly-over zone lying between the power triangle of D.C.-N.Y.-L.A. From now on the average American belongs to a vast, vague abstraction known as “the American people,” which is subdivided into cardboard-cutout cartoons such as soccer moms, former Reagan Democrats, and urban Bobos, and whose domestic concerns fall under the patronizing category of “kitchen-table topics.” (Pundits love to picture families gathering around the kitchen table to discuss prescription-drug benefits.) These residents of Munchkin Land need not concern you, since you’ll never have to meet them in the flesh, except in airports or town meetings where the caste system has broken down. Once you’ve joined the journalistic in-crowd and done your first of many E-mail chats on Slate, it’s time to draw the curtain in the first-class compartment. Where a reporter like Haynes Johnson used to take palm readings of the masses to support his woolly platitudes (in Kinsley’s parody of Agronsky & Company, he was Haynes Underwear, solemnly pronouncing, “For me to pass among the American people at this fleeting yet crucial moment in history, touching an outstretched hand here, accepting a gentle kiss on the foot there, was as stirring and moving for me as a journalist as it was for them as the American people”), today such dirty work can be shunned through the mediation of polls. Every pundit must be as conversant with polls and pollsters as a market analyst is with support levels and significant tops, able to divine the deeper booga-booga of conflicting numbers issuing from Zogby and Rasmussen. “Well, as you know, Brit, polls taken on Friday nights skew Democratic since more Democrats are likely to be home watching The Fugitive.” (“Skew”—a key verb in the pundit’s vocabulary.)

The old Walter Lippmann formalities have gone kaput. Chat is king.

Polling data are the white noise of political discourse, a jamming device to make public opinion seem decisive when it’s corporate money calling the shots. It’s not a conspiracy, this nonstop numbers babble, but a collusion, a nexus of converging interests. Corporate sponsors underwrite the pundit’s affluenza; they’re the ones buying the ads (where would Sunday-morning Washington talk shows be without those G.E. spots?), hosting the business conventions and expos, and sharing the skybox with your media bosses. It’s only natural that the pundit class would eventually gravitate to management’s point of view while offering lip service to “the mood of the people.” How can you align yourself with the workers when they keep losing your luggage? Led by Robert Novak, sneers at labor bosses have become a common slur in the pundit libretto. Germond states that McLaughlin was furious when he refused to cross a union picket line to tape the show. A fellow panelist, the supposed neo-liberal Kondracke, had no qualms about crossing the line (or sneaking around it), claiming the unions were “way out of control.” Anything that inconveniences Mort is clearly the mark of anarchy.

10. ALWAYS END WITH A HEARTY CHUCKLE

Pundit spats should never be taken personally. Ripping off your lapel mike and stomping out of the studio may feel good and look macho, but it will tend to cut down on future invitations. Remember, you and your fellow panelists belong to the same V.I.P. club—practice collegiality; tease but don’t torment. Nearly every broadcast of Crossfire and The Capital Gang ends with everyone enjoying a nohard-feelings chuckle as the credits roll. Chuckling isn’t as easy as it looks: to convey the shallows of phony bonhomie calls for a relaxed diaphragm and a nice twinkle. (Note the evident strain of the guests on Washington Week in Review laughing gamely at one another’s toothless whimsies.) Pundits incapable of producing a fade-out chuckle—such as Joe Conason, who was the Michael Corleone to Jack Newfield’s Godfather at The Village Voice, or the humorless tax-cut militant Grover Norquist—aren’t as welcome in the banquet hall as more congenial spirits. They’re booked, but not asked to join the regular roundtable. And then someday they won’t be asked back anymore, and they’ll sit in their lonely apartments, cursing the darkness.

A question from the floor:

—Are there any pundits you can recommend? Ones I could emulate without hating myself?

Yes. William Kristol of The Weekly Standard. He’s civil, sheepishly selfdeprecating (as befits Dan Quayle’s former chief of staff), willing to depart from the Republican script and entertain doubts and contrary findings (unlike his associate at The Weekly Standard, Fred Barnes, who’s squandered the journalistic

credibility he built up at The New Republic), and he doesn’t need to be grilled over an open flame to admit he’s made a bum prediction. Whoever made the decision to drop him from the lineup of ABC’s This Week deserves a dunce cap. James Warren of the Chicago Tribune has a sardonic, deadpan delivery. Bill Press started promisingly as the left side of Crossfire, but seems to be cashing in his brain cells as co-host of CNN’s The Spin Room, where he and the self-enamored Tucker Carlson (who yips at his own jokes) field phone calls and E-mails from ignoramuses. Newsweeks Anna Quindlen and The Nation’s editor, Katrina vanden Heuvel, were quite forceful on Charlie Rose’s coverage of the second presidential debate. And of course there’s our own excoriating Christopher Hitchens.

That’s about it.

Any other questions? Good. Now go out there and hit the hair spray!

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now