Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowCountry Chic

TALKING PICTURES

Stephen Schiff

Something odd is afoot at the movies. Up on the screen, parched-looking people in overalls are picking corn. The men have wispy crops of hair; the women's necks are as wrinkled as Japanese lanterns. And they're not people, they're "folks." Usually there are two children, the elder a boy who's very grownup and serious and who talks with his mouth clenched, as if he were afraid something ghastly might fall out of it. His parents say grace over dinner, and they sing hymns over the credits. And from the way they make goo-goo eyes during meals, you can tell they love each other. But what they really love—more than anything, in fact—is The Land.

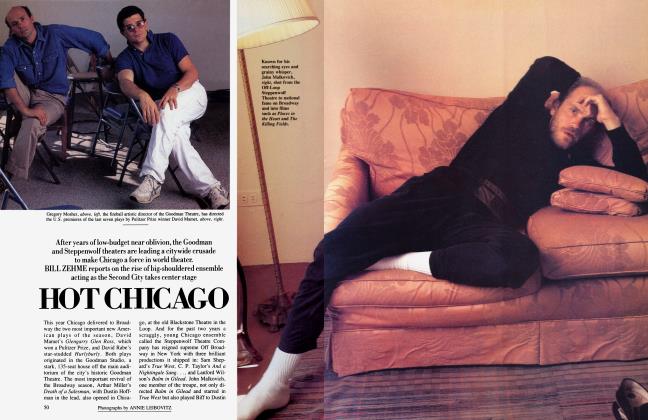

The name of the movie could be Places in the Heart or Country or, coming soon to a theater near you, The River. These are farming pictures, and they're the crest of a wave that's been building for a long time, from Days of Heaven and Resurrection to Raggedy Man, Tender Mercies, and The Stone Boy. Hollywood, renowned purveyor of soap operas, space operas, and intrepidarchaeologist operas, has given birth to the New American Pastoral, a wholesome, milk-fed genre that's actually a stem ritual of atonement in disguise— which is why these new movies feel strangely tenuous and inauthentic. They aren't really about cotton pickers and hymn crooners. They're an outburst of cultural guilt—especially Hollywood's guilt over the film industry it has ruined.

The impulse behind the New American Pastoral is not so different from the one that made this year's Olympics such an orgy of devout nationalism, or the one that's fueling America's current frenzied efforts to fill its spiritual hollows. It's the impulse to believe in something, to slice through the Yuppie fog, to Learn to Care Again.

For years, our most popular movies have been glittery consumer items— wide-screen, Dolbyized tchotchkes. After watching Flashdance or Ghostbusters, you buy the T-shirt, play the record, adopt the fashion. The fantasy becomes yours only when you can own a piece of it. Contemporary blockbusters enter our lives by shoving themselves out at us, whereas good movies used to beckon us in; they used to invite us to enter the lives on the screen. Today's filmmakers know they're spewing out cinematic sludge, and the stench is getting to them. They're angry at the system, and at audiences for supporting pictures even the directors don't respect, but most of all they're angry at themselves for submitting. After all, no one ever journeyed to Hollywood with dreams of Bachelor Party dancing in his head. The vast majority of filmmakers want to express themselves, reveal beauty and truth.

Unfortunately, they don't know much about those things. Oblivious to any world outside the business, these corroding idealists have a hard time remembering exactly what basics they're trying to get back to. God? Literature? Lower cholesterol? How about The Land?

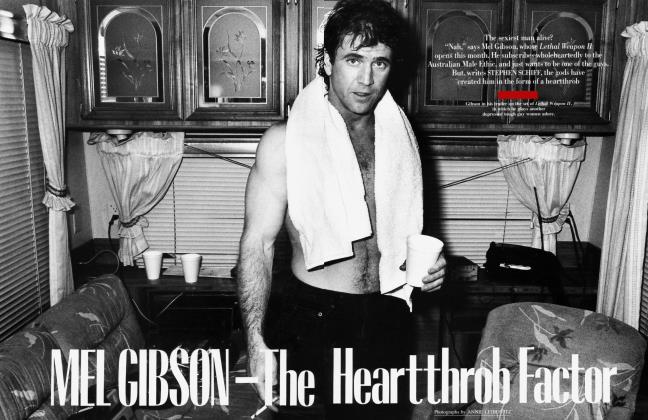

The products of all this soul-searching aren't terrible. The New Pastorals are spirited, craftsmanly, blessed with homely insights. And they have impeccably hip casts full of down-home types like Sissy Spacek and Sally Field, renegade beauties like Jessica Lange and Mel Gibson, and, best of all, honest-toPete theater people—Ed Harris, Lindsay Crouse, John Malkovich. The sacramental presence of Sam Shepard in four recent pastorals (and his screenwriting credit on a fifth, Paris, Texas) is like the High Culture Seal of Approval. And yet none of the ones I've seen has seemed quite sincere. For all their livedin dungarees and rattletrap pickups, these films are weirdly ostentatious. They wear their nobility on their chest like a campaign button—it's conspicuous caring. More alarming still, they all tell the same story, with the same pair of enemies—the big, destructive storm (The River gives us two) and the moneymen who are trying to take the farmers' land away. The common folk always band together to defeat the wealthy plunderer; the longed-for lump always rises in the collective throat. How is it that a genre so young is already so clotted with cliche? The talk in these movies groans with the sort of jes'-folks jabber you used to hear in such Old Hollywood pastorals as The Southerner— or Ma and Pa Kettle. Yup. I reckon. I'd be most obliged. And in a film like Places in the Heart, where blind men, downtrodden blacks, widows, derelicts, and helpless children crowd the screen like so many beggars soliciting our tears, you wind up feeling like a sahib touring Calcutta.

But 1 think I understand why these New Pastorals look so distant and contrived. They aren't really about farming, they're about filmmaking; they're metaphors for the director's heroic struggle to get his dream on the screen. Recasting himself as the guileless and fiercely independent man-of-the-soil, the filmmaker relives the battle against his implacable foes: the weather, which ruins location shooting and puts him behind schedule and over budget, and the moneymen, who are always on his back, always changing the rules, always trying to wrest the property from his control. That's why such an air of selfpity drips through these films. Consciously or not, the poets of the pastoral are bemoaning their fates. They're using the American (/r-metaphor of The Land to glorify their own loamy piety. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now