Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowEating Around

The things restaurants do when they recognize a critic would curl your arugula

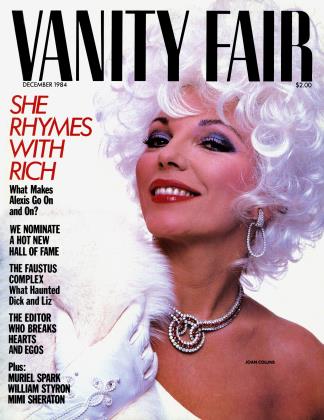

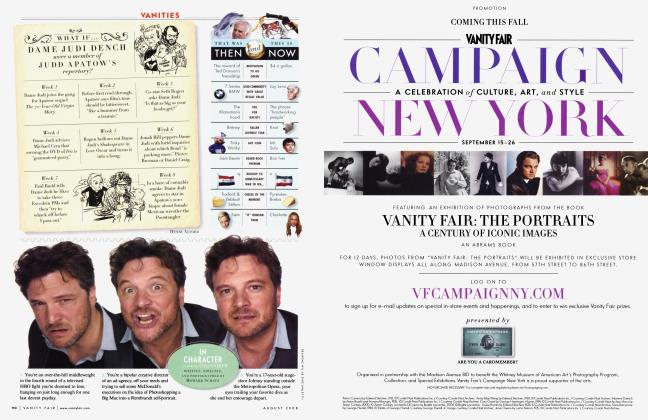

Vanities

RESTAURANT critics who want to perform their tasks unrecognized pay a heavy price: no celebrity parties at the newest hot eateries, no appearances on television talk shows, no profitable cooking demonstrations, and no autograph sessions in B. Dalton’s bookstore. Many critics, therefore, decide to forfeit anonymity. Asked if they do not feel that being known is a handicap when trying to ascertain how the general public is fed and served in this or that restaurant, they swear that it is not. If pressed, most of them will admit that, yes, the service they get is especially careful and that they are likely to be given a choice table. But what, they argue, can a chef do with the food once a critic is seated?

Any so-called food expert who asks that question has to be a fool or a liar.

Through the years, I have learned many of the tricks a wily chef who spots me in his restaurant can pull out of his starchy sleeve. To perform them, he must of course realize that there is something wrong with the food he generally dishes up; if he isn’t aware of that, I get what everyone else gets, only more of it. Some of the tricks are blatantly simple, such as exchanging stale bread for fresh or removing cutinto cakes and pies and bringing out fresh, whole ones, clearly intended for the next meal.

“But what about other foods that must be prepared in advance?” runs the standard query. Plenty about it; and there is no better example than a pate, which is about as cooked and unredeemable as a dish can be. Once again, the chef can easily remove the first slice if it’s stale and dry, and serve it to someone else. If a pate is really old, he can bring out a fresh one. Ditto for a desiccated remnant of smoked salmon. He can thin, thicken, or reseason soups and stews, and if they contain costly ingredients, such as lobster, crab, or truffles, he can heap an extra-generous amount on the critical portion.

A canny critic has to keep an eye on the traffic pattern in the dining room. Frequently, what he sees on the hors d’oeuvre wagon may not be what he gets, especially if what he sees seems to be high or rancid. In that event, his plate will be sent to the kitchen for fresher celeri remoulade or moules vinaigrette.

All dishes that are cooked to order, of course, can be done with extra care when a critic is on the premises. Overor undercooked fish, steak, or chicken can be palmed off on another guest while a second effort is launched on the critic’s behalf. That practice is so common that I now regard a long wait between courses as a sure sign that I have been recognized and that my food is being rendered in at least four versions, in the hope that one will be right.

Many Chinese, Mexican, and Indian chefs tend to go lightly on the authentic seasoning of their ethnic dishes—especially hot chili peppers—in their desire to attract the broadest possible clientele. They also use oil that is not fresh, and cook on dirty woks or griddles—unless, that is, they sense that a rating is about to be laid on them. Often their efforts then result in overkill, with choking amounts of seasonings that provide a clue to their insincerity. Known to dislike food that is undersalted, I am often served dishes so bitingly salty that I know immediately how and why they got that way.

At times, there really is nothing an owner or chef can do. Suppose he has scorched a batch of spaghetti sauce, or he is out of fresh fish or chicken. In such instances he will usually tell the critic that he has just sold the last order of the dish in question.

The most dramatic switch for me took place in a restaurant whose owner had another establishment across the street. His number-one chef was also across the street, but not for long. A few minutes later, in he marched, overcoated and whiteaproned, along with two of his assistants—just in time to prepare my order.

Other restaurateurs who have noted my presence have picked the iceberg lettuce out of my salad, piled eight shrimp in a cocktail that normally consisted of five, and served me such bonuses as a whole duck instead of a half and homemade salad dressing instead of the bottled slime everyone around me was suffering through.

Difficult though it may be to develop them, there are a few techniques the wily critic can use to counteract the effects of recognition. But you’re certainly not going to find out what they are from me.

Mimi Sheraton

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now