Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowBooks

TOUGH CHICKS DON'T WEAR MITTENS

JAMES WOLCOTT

JAMES WOLCOTT compares two young novelists following different paths to literary stardom

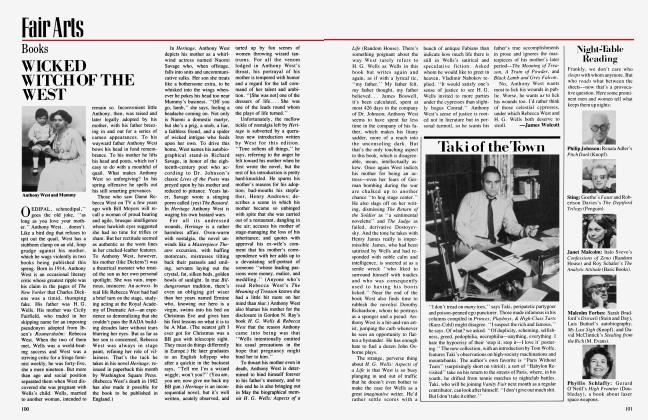

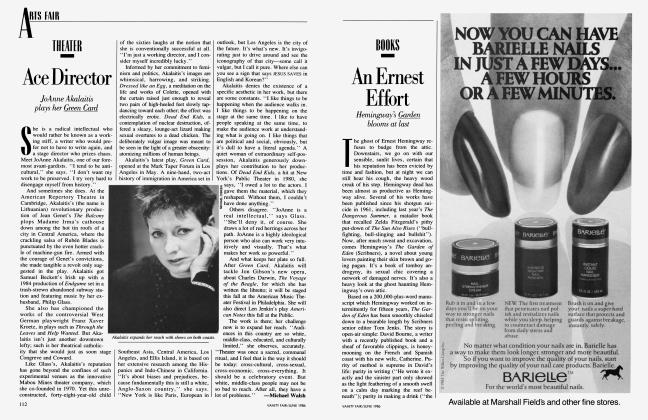

T AYNE Anne Phillips, with J her long, flowing hair and sympathetic brow, looks like the most sensitive coed ever to press sonnets to her bosom. Kathy Acker, with her punky fork cut and defiantly bared shoulders, looks like the most resourceful street rat ever to feast upon society's crumbs. One appears English-major-y and demure, the other unschooled and rabid with loathing. But as writers Phillips and Acker might have been shot out of the same starting gate, so swift and parallel have been their careers.

Both are in their early thirties; both began publishing in smallpress editions, graduating to the biggies; both derive inspiration from William Burroughs, whose cruel, deranged sentences might have been written by a syringe dipped in acid; and both are, in their own cult realms, stars.

In their fiction both take on the role of daughter, but what different daughters they are! Jayne Anne Phillips seems to be the mild sort who keeps her voice low when Mom's asleep, and draws the curtains to soften the light. Kathy Acker, flicking lighted matches at the stove, tries to burn down the house so that she can bawl on every corner that she ' s an orphan. Yet it ' s the dutiful daughter who proves to be the true toughie.

Although Phillips's celebrated first collection of short stories, Black Tickets, had its gentle moments of emotion (particularly in "Home" and "Souvenir"), the book was far more noticeable for its spiked, torn lyricism—its kiss-myboots swagger. "She remembered swerving, cocaine lane, snowy baby in her veins," began one story. "Jamaica Delila, how I want you; your smell a clean yeast, a high white yogurt of the soul," began another. Black Tickets was a book that prided itself on razor nicks and dirty fingernails, on being able to create sparks of poetry by scraping bottom, and the shock of Phillips's first novel—Machine Dreams, just published by E. P. Dutton—is that it's so self-subdued, so free of rough knocks and impurities. Priming itself for lift-off, Machine Dreams opens with not one or two but four introductory quotations, including contributions from Hesiod and Laurie Anderson, the juxtaposition of which we're meant to find droll. All of the citations involve flight, and that's what the novel is about— the quest for flight and transcendence, and how fate and gravity bring that quest to crashing ruin. For all of this rigmarole, Machine Dreams isn't as dire as one might fear.

Jayne Anne Phillips has always had limber vocal cords in her fiction, and Machine Dreams is essentially a suite for voices. Chronicling the life of a single family, the novel passes the microphone from one character to another, with Phillips herself serving as an off-camera commentator. Gone are the askew, narcotic flamboyances of Black Tickets. The language here is quaint and homespun, wrapped in flannel. "Ava died at a hundred, think of that. You remember her funeral. That was the old family plot. Snowing so hard no one could drive past the gate and they had to walk the casket up. Bess took the death hard." Yup, there's a heap of dying in Machine Dreams, and Phillips's plain, muted manner recalls the lonesome fiction of Sherwood Anderson, which was also rich in gravestones, silence, and snowfalls. Like Anderson, she sometimes succumbs to bathos, which in her case becomes soap-opera bathos. Quiet on the set, everybody. Action!

"It's three in the morning," he said. "What the hell is wrong with you?"

Her voice was weak. ''I'm pregnant again." She wiped her eyes with the back of one hand and looked into the pan.

He walked nearer and touched her shoulder.... "What's wrong with that, now?" he said more gently. "We're married, aren't we?"

"But Danner's only six months old, and you were just saying tonight how slow it is at the plant, and with all the bills from this house—"

Like sands through an hourglass, these are the Days of Our Lives.

Yet if the reader is willing to wade through acres of ankledeep suds, the last third of the novel rewards the effort. As Machine Dreams inches into the late sixties (its opening chapters are set in the lull before World War II), the young man who dreams of flight, Billy Hampson, chucks college and enters the army, where he hopes to get into an aircrew and "keep [his] ass in the air. ' ' His ass eventually ends up in Vietnam, where it tumbles earthward, lost in a fire zone west of Tay Ninh. As banal as Vietnam's appearance in this novel is, as open to facile pathos as the plight of the M.I.A. is, Phillips nevertheless manages to create a widening pocket of sorrow comparable to the hollow of death that opened in Virginia Woolf's novel Jacob's Room (which was also about war and bereavement). Once Phillips begins to trace the arc of Billy's dying fall, she seems to tap something deeper in herself; she goes beyond verisimilitude, no longer content to whittle sentences out of choice pieces of hickory. Jayne Anne Phillips writes more commandingly in shorter bursts, where tension and feeling can be shaped into concentrated doses, and Machine Dreams, stripped of all its apparatus, would have been far better as a novella. It's as if Phillips wrote it as a full-scale novel to prove that she was capable of more than burning fragments. Now that she's gotten this big baby out of her system, perhaps she can relax and regather her forces. Like light through a magnifying glass, Phillips's talent arouses flame when it is most focused.

Kathy Acker, by comparison, sprawls all over the sofa with tramp insolence. Acker is currently quite a rage in London, where she has been featured in The Face and Harpers & Queen, and was the subject of a report on television's The South Bank Show (where she told England, "I never knew who my father was. My mother hated me. The only love I ever got was through sex, which I had very early"). An "electric opera" with a libretto by Acker had its premiere in Rotterdam in April, directed by Richard Foreman. And in New York, Acker's legend as a low-life demon capable of drinking wino's blood from a rusty can is long-standing. Although I had been hearing about Acker for years, I had never really read her until I picked up Blood and Guts in High School, Plus Two (Picador), which features more than four hundred pages of Acker material, including poems, plays, parodies, and Artaud-like declarations. I settled into the chair, and as I read, shock stupefied my forehead and dismay lowered my jaw like a drawbridge. There's no skittering around the truth: She's ...awful. Illustrated with scratchy drawings of jumbosize genitalia, Blood and Guts in High School is a long, clumsy bang on the bongos about bad sex and bad chemicals, with sentences only a beatnik madonna could scrawl. "I want: every part changes (the meaning of) every other part so there's no absolute/heroic/dictatorial S&M meaning/part the soldier's onyx-dusted fingers touch her face orgasm makes him shoot saliva over the baby's buttery skull... a tongueless canvascovered teenager pisses into the quart of blue enamel he's holding in his half-mutilated hand... " etc. Kids today, they sure keep you hopping. Rape and bondage are the busiest activities in Acker's fiction, her heroines' orifices carrying a lot of rough traffic, their nipples caressed by riding crops.

Kathy Acker appears to have modeled herself on the former punk-rocker and poet Patti Smith. Like Patti, Acker has been photographed by Robert Mapplethorpe; she studs her fiction with references to the rock club CBGB (where Patti first made her name); and they share a lot of the same culture heroes (Burroughs, Pasolini, Jean Genet). Once, at a poetry reading, I heard Patti Smith reel off the names of the writers she most admired, not only Burroughs and Genet but Verlaine and Rimbaud, and as a tossaway explanation she added, "You know, those tough faggots. . .let's face it, they're the ultimate cool guys.'' That's from where Acker seems to draw her notion of cool as well. It's a weird form of penis envy, this desire to write like a tough faggot. Patti Smith at least had a sense of humor about her fan worship, and her own driving, offbeat sensibility; Acker acts as if a person were incomplete without a terrorizing phallus. Why, despite her blatant lack of originality, has Kathy Acker become such a hot ticket? Now that Patti Smith is a housewife in Michigan and Laurie Anderson has gone shinily upscale, there seems to be a position vacant for a bohemian cult heroine which Kathy Acker, guns ablazing, has rushed in to fill. Publicity breathes from her every pore. Despite a certain show-offiness, Jayne Anne Phillips has a reservoir of talent that flows in original directions. Not Kathy Acker. She's a phony from the ground floor up.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now