Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWeston World

PHOTOGRAPHY

A centennial survey of the man and his myth

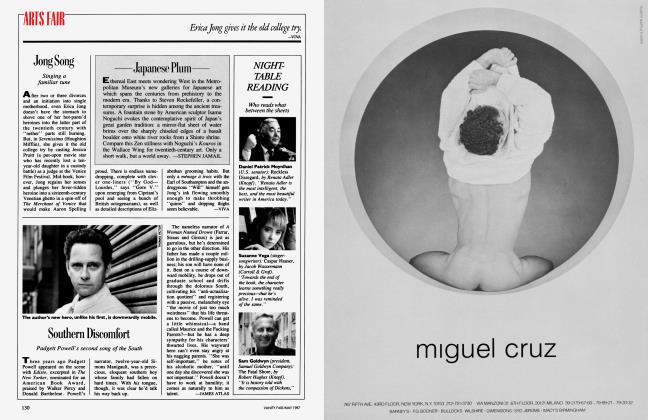

The photographs Edward Weston made between 1925 and 1940—semiabstract compositions of nude bodies, faces, rocks, and vegetables— practically define the heroic age of American photography. His posthumously published Daybooks—half diary, half manifesto—provide a classic example of the artist as modem martyr. This year is the centennial of Weston's birth, and this month the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art opens "Supreme Instants," a fullscale survey of his work. Selected by Beaumont Newhall, dean of photo historians, the show promises an in-depth view of an artist who was a mass of contradictions. A proselytizer for sharp-focus, "straight" photography, Weston frequently resorted to darkroom manipulation to improve

on his negatives. A vociferous vegetarian, he loved bullfights. A family man with four sons, he embraced countless mistresses. Weston today might seem to suffer from overexposure; every amateur imitates his eerie dunescapes and his sensuous still lifes of gnarled vegetables, while slick commercial photographers copy the

poses of his nudes. But the original images retain a vital force of their own. The very best photographs in the show may be Weston's portraits: violent, unflattering close-ups that seem as shocking today as they did fifty years ago.

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. (1117-1118)

#%f age thirty, choreographer Mark Morris is the pre-eminent craftsman of his generation. With his wild range—he touches here on Vivaldi, there on wrestling or classical Indian dance—this Seattlebased iconoclast consistently shuns the limelight and stuns the critics. This month, at the Brooklyn Academy of Music's Next Wave Festival, Morris presents a new group work set to Pergolesi's euphonious Stabat Mater. Miss this one at your peril.

—CRAIG BROMBERG

PEPE KARMEL

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now