Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

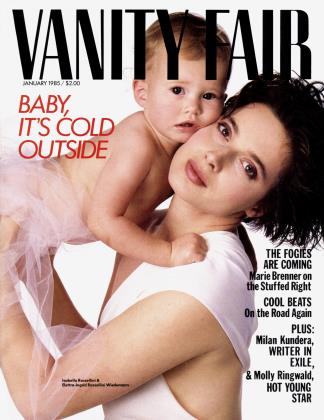

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowDesigner of the Decade

ARCHITECTURE

ARTS FAIR

For such internationally acclaimed works as the High Museum of Art, in Atlanta, Georgia, and the Atheneum, in New Harmony, Indiana, fifty-year-old RICHARD MEIER is acknowledged as one of the world's leading architects. Last spring he became the youngest recipient of the Pritzker Prize, architecture's most distinguished award. Now he

has won the hotly contested commission for the new J. Paul Getty fine-arts center, in Los Angeles. The 450,000-square-foot project, on which construction is due to begin in the fall of 1987, will cost, by conservative estimates, more than $100 million. Here, he tells BARBARALEE DIAMONSTEIN what's in store.

Your work is strongly influenced by the modernist master Le Corbusier. Did you ever meet him?

Twice. The first time was when I graduated from architecture school and traveled in Europe. At that time I had the idea that I might stay in Europe and work for a while. I went to see a few architects, and the first one was Le Corbusier. I went to Paris and knocked on the door of 35 rue de Sevres, and of course was told that it was not possible to come in. So I said, "I have my portfolio with me. I'd like to have an interview for a job." And that didn't work. So I stayed in Paris for a while, and one day I was at the Cite Universitaire—it was at the time of the opening of the Maison du Bresil, designed by Le Corbusier and Lucio Costa, the Brazilian architect. Le Corbusier was there an hour or two before the actual dedication ceremonies for the building, so I went up to him and said that I'd tried to see him and was interested in working for him and would like to come as an apprentice. But he wouldn't hire me, or any other American architect. He had occasionally been disappointed in his dealings with Americans over the years.

You've been called a "second-generation Corbusier'' and a "neo-Corbusian." What is it about Le Corbusier's work that attracted you?

Almost every student of architecture, at least at the time I was in school, was influenced in a major way by four architects: Frank Lloyd Wright, Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, and Alvar Aalto. Le Corbusier's work in particular made a very strong impression on my fellow students at Cornell. Two great Corbusier works—the pilgrimage church at Ronchamp and the monastery at La Tourette—had been recently completed, so his influence was in the air. There's not an architect practicing that in some way hasn't been affected by Le Corbusier. I don't deny having learned from him or that our work has some similar aspects, but I don't consider myself a ''second-generation Corbusier." In my work, the conceptual and spatial organization is very, very different from Corbusier's. Six years ago, you described Frank Lloyd Wright's Guggenheim Museum to me as the single most important piece of architecture in New York City. Do you still think that is the case?

I would say, if it isn't, what is?

Are you, then, more influenced by Wright than by Le Corbusier?

Wright's Fallingwater, at Bear Run, certainly was a very, very strong influence in the design of one of the first houses for which I was commissioned—my parents' house in Essex Fells, New Jersey.

Besides Le Corbusier's and Wright's, whose work do you admire?

I am also inspired by Borromini, and by Bramante, and by the German Baroque architects, like Balthasar Neumann. The great Baroque churches in southern Germany are fabulous. When you look at the quality of light and the way that natural light enters the spaces of those churches, there's much you can learn.

The location selected for the Getty art complex is 742 acres of what has been described as ' 'gold dirt' ' on a promontory in western Los Angeles. Have you ever designed a building for a site that has presented so many challenges?

No. To the best of my knowledge, no one in recent times has designed anything for a site like it.

Why is the location so extraordinary?

The terrain is spectacular. The site is highly visible, on the comer of the San Diego Freeway and Sunset Boulevard. It can be seen from great distances as well as by passing traffic in four directions. The hillside has magnificent views to the east, to the center of Los Angeles, as well as west to the Palisades and the Pacific Ocean. It's a very exposed site, so there is the danger of fire sweeping across to it with the Santa Ana winds. It's going to be an interrelated complex of buildings, with access from the freeway—there are questions as to how to approach the site and how to get up into the public spaces to use the museum. It's a site for which a great deal of thought has to be given to the nature of the landscape, both in terms of its relationship to the building's shape and how the building itself will affect the land around it. Also, there's the quality of light. The light in California is very different from the light on the East Coast. There are many, many considerations in terms of how one utilizes the site for all the diverse activities that are now planned to take place there, as well as for activities not yet thought of.

The complex is to include a museum, a center for studying the history of art and the humanities, and the Getty Conservation Institute. What will each structure contain?

The museum will house the existing collection of decorative arts, as well as the present Getty's collection of sixteenth-, seventeenth-, eighteenth-, and nineteenth-century painting. The study center will contain one of the most incredible libraries on art, architecture, photography, and graphic arts ever assembled.

What will be your major design concern—the site, the nature of the collection, ecology, crowd circulation, or the West Coast location?

All of them!

How do you see the role of the museum as architecture in relation to its role as showcase?

The important thing is the relationship between the viewer and the art. One of the things I've tried to do is make it possible to see a work of art more than one way—so that there's not only a oneto-one relationship when you're looking at art but also an opportunity to see it from different perspectives as often as possible.

And what do you see as the possibilities of the new Getty?

As far as I can tell, this is perhaps the most important major public institution of its kind. There have been a lot of museum buildings built in the last ten years, and there has been a lot of activity in the building of cultural institutions. I don't see that continuing, and I can't imagine a museum or cultural institution being planned that can in any way compare to the Getty. The purpose here is to go beyond what's been done anyplace else and make the best museum that is possible. It will be a place in which there are both major private and major public aspects. I've never had a site

with this kind of opportunity.

So the Getty is a dream assignment?

It's the most desirable commission that I could be working on for the next ten years.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now