Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowBOOKS

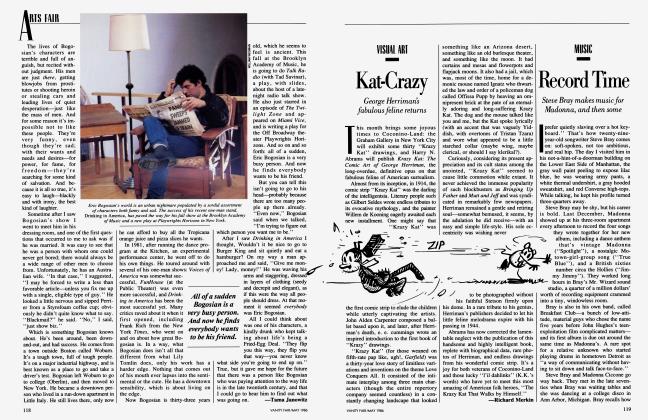

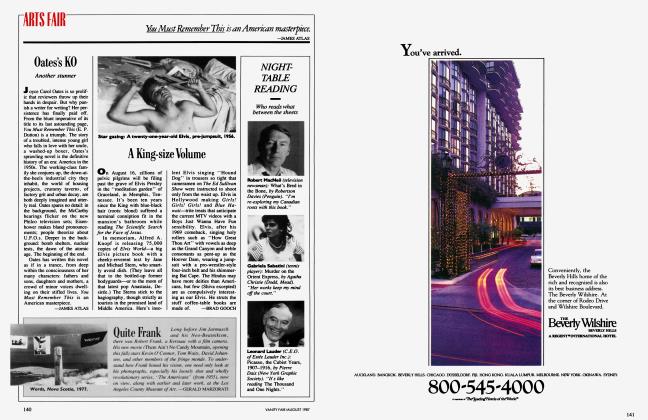

ARTS FAIR/BOOKS

Hot Type

William S. Burroughs's novel W Queer (Viking), written in 1952 but unpublished until now, is a quirky love story in which Cupid's arrow is tipped with curare. It's the tale of an American in Mexico City, William Lee, who tries to hit on a dirty-blond, Eugene Allerton. Unlike most romantic novels, Queer does not trade in psychological urges and surges. Rather, Burroughs's take on sex and love is immunological: the lover is a virus trying to invade, or "contact," a resisting body.

Here in prototype is the notion that was to become the very current of Burroughs's prose in Naked Lunch and Nova Express: that foreign substances, viral, pharmaceutical, or demonic, are vying for control. His own prescription, set down in a new introduction to this manuscript: "writing as inoculation." Burroughs once crankily asserted that "paranoia is having all the facts." It's fascinating to watch the artist as a young paranoid piecing together his case.

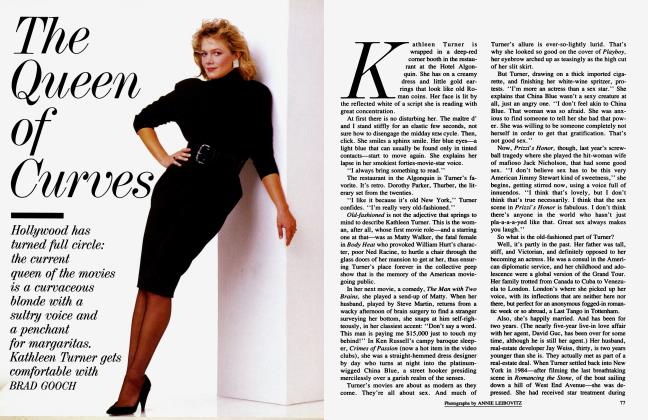

Brad Gooch

In his eightieth year, Stanley Kunitz brings forth Next-to-Last Things (Atlantic Monthly Press). Its opening poems terrify and instruct—through the haunted mind of an itinerant repairman, the cold eye of a beached whale. We are then led into passages of incandescent prose gathered from the "vaults of memory," where "everything unforgotten is equally real." Robert Lowell is alive again, "slumped onto your sofa like an extended question mark," and childhood is returning "out of the mists." In these essays, memoirs, aperqus, and aphorisms is revealed "the occult and passionate grammar of a life," and the mind as a "self-contained universe turning on its obsessional axis." The poet's father, drinking carbolic acid in a public park before the poet's birth, becomes many men, mythic and real; the poet's mother is led onto the page to speak for herself in an act of uncommon intimacy.

This is an autumnal work of remembrance and forgiveness, at times portentous, but always instructive. Questions about the life and importance of the poetic imagination in twentieth-century America have not been so well addressed anywhere else, nor with greater simplicity. Mr. Kunitz is a living treasure, and his newest book a blessing.

Carolyn Forché

With characteristic Borgesian aplomb, it is announced in the prologue to Atlas (E. P. Dutton) that this book is certainly not an atlas. Instead, Jorge Luis Borges points to the reason behind the book: a collection of casual photographs, with text, from his travels with Maria Kodama through Istanbul, Ireland, and Greece to California and Buenos Aires. There are also poems and musings upon such disparate things as "Fountains," r g ' 'The Temple of Posei‡ don," "The Brioche," TheTotem."

Atlas is a collection of meditations, not, as the dictionary has it, a collection of maps. Yet in a profound and elusive way it really is an atlas. For each meditation is a guide to what Borges calls an archetype. This holds true also of the poems, as in "Wolf," a melancholy depiction of the last such animal in the England of antiquity, hunted to death by decree—the archetype of a creature ferocious, banished, and nearly extinct. So in the end we have a collection of archetypes, a strange and enjoyable book, and a monument to what Borges calls "that long adventure which still goes on."

Eve Ottenberg

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now