Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowOut to Lunch

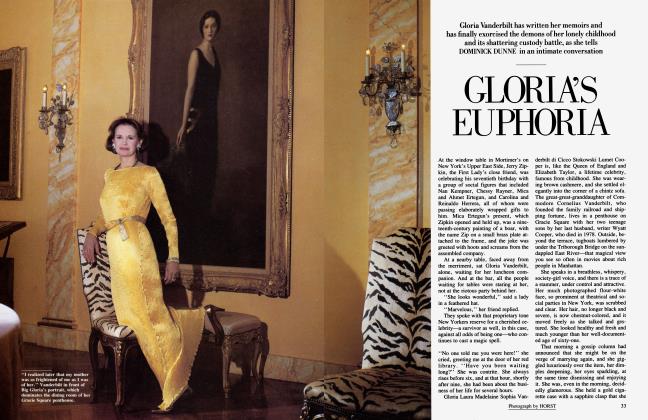

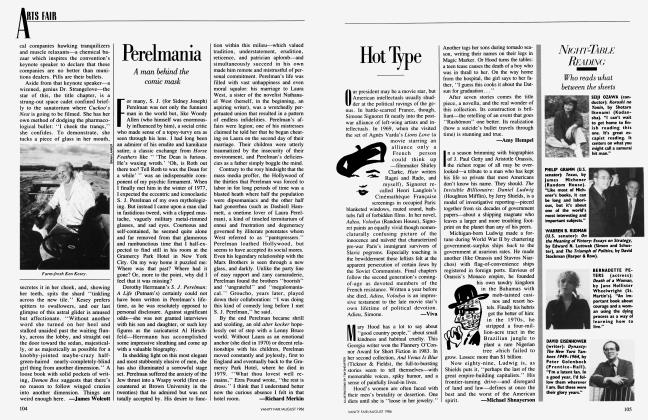

with Linda Ellerbee NBC's resident news-wit dines on chili con AMY HEMPEL

Linda Ellerbee, who used to keep us up late watching NBC News Overnight, is now waking people up with her "TGIF" column Fridays on the Today show. Reason enough to congratulate her over lunch. She suggests the Manhattan Chili Co., and we meet there two days later.

An occasional jade tree garnishes the spare pink-and-green room. We take a window table facing Bleecker Street. Even out of the sun Linda hides her gold eyes behind large tinted glasses. Ditto the pretty face behind dark, layered hair. She's wearing jeans and a pea jacket, the kind of clothes that caused confusion on the campaign trail during the primaries. ("Why is an electrician asking me questions?" she overheard the governor of New Hampshire saying to George Bush.)

Linda is from Texas. "Much of my life is spent in search of decent Mexican food," she says, picking up the menu. This place has something called "Texas Chaingang Chili for the Criminally Insane," which we pass up in favor of what Linda calls "real" chili, the kind without beans in it. The Chili Co. is near her house in the Village, where she is still stopped by people wanting to know why Overnight was canceled.

She dropped out of college at nineteen and has been a full-time journalist since 1971; she has been married and unmarried, and lived for a time on a commune. In the early seventies she found herself in Juneau, Alaska, "without a husband, without an education— but with a one-year-old and a two-yearold to raise." There was, she insists, "no dream, no vision, no ambition. I just needed the money to raise two kids.

"I'm not the typical woman on television," she says, "and I don't have the same ambitions"—a word which usually translates into anchoring nightly news. "I am less concerned with how often I'm on than what I'm doing when I am on."

Her Today segment is a wry week-inreview. When the World Court ruled that it would try the United States for possible crimes in Nicaragua, Linda showed clips from Sandinista television which portrayed the U.S. as though it had already been declared guilty. "And the opening to their newscast looked as if they'd hired Frank Magid as consultant"—the man who developed "happy talk" news—"all bouncy music and Minicams and happy Nicaraguans."

Linda has an attitude. On Overnight she won us over with comments like "Back to more depressing news..." Now she brings to our attention the Ann Landers survey which discovered that 72 percent of her female respondents preferred a hug to sex. Not fair, said Chicago columnist Mike Royko; no one asked men. Royko's own survey proposed that replies go to his "Sex or Bowling Clinic." Still not fair, Linda pointed out: "No one offered the women the option to go bowling."

Not that it's easy to be funny on network news. A friend, writer Roy Blount, Jr., likens it to being funny in church. And he wondered how she had that edge at 7:30 in the morning.

I asked her.

"Because I haven't just gotten up. I've been up," Linda explains. "Thursdays I come in at noon, and stay until noon on Friday."

She drags a tortilla chip through the chili con queso. "You know, every show of which I have been a regular part has been canceled—Weekend, Overnight. . .The Today show has been on the air thirty-three years"—she is laughing now—"I consider it my greatest challenge."

Another challenge is the book she's writing on TV news with her former partner from Weekend and Overnight, Lloyd Dobyns. "I was never a foreign correspondent, so Lloyd's writing about that; Lloyd was never a political reporter, so I'm doing that.

"I like to write about politics," Linda says, "but that's not the same thing as liking to cover politics. I think it's quite right to put a critical distance between yourself and the White House. On the campaign trail, there's not even time to research where the candidate's money is coming from."

A dish of jalapeno jelly beans is placed on the table. Linda lights what must be her tenth cigarette. "Like most people, I'm an absolute coward about making a big fool of myself in public. Which of course leads to the question of why do I work in television, where in the shake of a lamb's tail you can make a fool of yourself in front of millions of people— and we all have."

How does she cope with the tenuous nature of her business? What about the double standard whereby, as Linda recalls, in 1981 fifty-year-old Barbara Walters was considered the "grande dame of television news," while Dan Rather at fifty was "the brash kid who replaced Cronkite"? How has she retained her sense of herself?

"From the first day you go to work, you say, 'I will give in this much and no more.' It may not make you popular, but it's guaranteed not to make you part of the woodwork, and—

"I didn't order this," she says as the waiter, unbidden, sets a second margarita in front of her. She hesitates—the hours of work ahead at NBC—says, "Oh, all right," and lifts the glass. "So I won't use verbs this afternoon."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now