Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowGOING

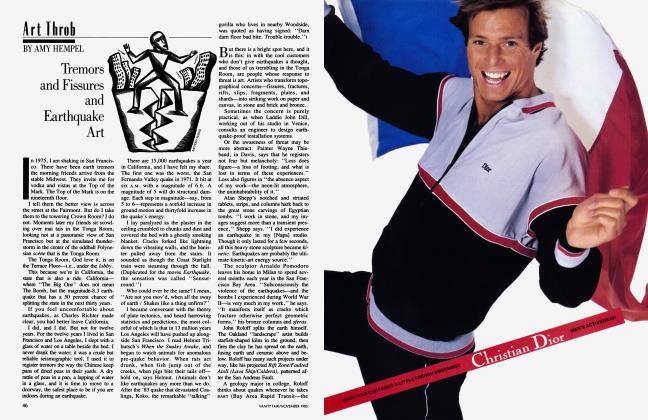

AMY HEMPEL

A short story by AMY HEMPEL, a bright new talent whose first collection will be published next year

There is a typo on the hospital menu this morning. They mean, I think, that the pot roast tonight will be served with buttered noodles. But what it says here on my breakfast tray is that the pot roast will be severed with buttered noodles. Severed is not a word you want to see after flipping your car twice at sixty miles per and then landing side up in a ditch.

I did not spin out on a stretch of highway called "Blood Alley" or "Hospital Curve." I lost it on flat, dry road with no other car in sight. Here's why: In the desert I like to drive through binoculars. What I like about it is that things are two ways at once. Things are far away and close at the same time.

In the ditch, things were also two ways at once. The air was hot and my skin was needling cold.

"Son," the doctor said, "you shouldn't be alive."

The impact knocked two days out of my head, but all you can see is the cut on my chin. I total a car and get twenty stitches that keep me from shaving.

It's a good thing, too, that that is all it was. This hospital place, this clinic—it is not your City of Hope. The instruments don't come from a first-aid kit, they come from a toolbox. It's the desert. The walls of this room are not rose beige or sanitation-plant green. The walls are the color of old chocolate going chalky at the edges. And there's a worm smell. Though I could be mistaken about the smell. I'm given to olfactory hallucinations. When my parents' house was burning to the ground, I smelled smoke three states away.

Now I smell worms.

The doctor wants to watch me because I knocked my head, so I get to miss a few days of school. It's okay with me. I believe that 99 percent of what anyone does can effectively be postponed. Anyway, the accident was a learning experience. You know—pain teaches?

One of the nurses picked it up from there. She was bending over my bed, picking pebbles of safety glass out of my hair. "What do we learn from this?" she asked.

It was like that class at school where the teacher talked about Realization, about how you could realize something big in a commonplace thing. The example he gave, and he said it really happened, was that once while drinking orange juice he realized he would someday be dead. He wondered if we, his students, had had a similar realization.

Are you kidding? I thought. Once I cashed a paycheck and I realized it wasn't enough. Once I had food poisoning and I realized I was trapped in my body—but not as much as I wanted to be.

What interests me now is this memory thing. Why two days? Why two days? The last I know is not getting carded in a two-shark bar near the Bonneville flats. The bartender served me tequila and he left the bottle out. He asked me where I was going, and I said I was just going. Then he brought out a jar with a scorpion in it. He showed me how a drop of tequila on its tail makes a scorpion sting itself to death.

What happened after that?

Maybe those days will come back and maybe they will not. In the meantime, how's this: I can't even remember all I've forgotten.

I do remember the accident, though. I remember it was like the binoculars. You know—two ways. It was fast and it was slow, and both at the same time.

The pot roast wasn't bad. I ate every bit of it. I finished the green vegetables and the citrus vegetables too.

Now I'm waiting for the night nurse. She takes a blood pressure about this time. You could call this the high point of my day. That's because this nurse makes Tina Turner look like a sex change. Unfortunately, she's in love with the Lord.

But she's a sport, this nurse. When I can't sleep she brings in the telephone book. She sits by my bed and we look up funny names. Calliope Ziss and Maurice Pancake live in this community.

I like a woman in my room at night.

The night nurse smells like a Christmas candle. After she leaves the room, for a short time the room is like when she was here. She is not here, but she is.

It's not the same, but it makes me think of the night my mother died. Three states away, the smell in my room was the smell of her powdered face when she kissed me good night—that night she wasn't there.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now