Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowHot Heirs

John Sedgwick records the life-styles of the rich and aimless

WHAT would life be like with a lot of money, a real flood of it?. . .Would it be lovely? Would it be different? Would it be fun?' ' Boston-based writer John Sedgwick wanted to know. In 1982 he'd just read Edie, the splashy best-seller depicting the short, shrill life of his first cousin. "It made me start to think about what money does to people," he says, "and I realized I had unique access to the world of the rich. "

Sedgwick made some phone calls and later traveled to seven cities, hooking up with fiftyseven young inheritors—Rockefellers, Mellons, and Grahams among them. Behind closed portals he listened to babble about exotic tours, racy cars, charity work, depression bouts, and spiritual scrambling. Or, as he writes in Rich Kids, out this month from William Morrow, their flights to "cleanse themselves of their original sin of coming into money."

The book seems tailor-made for Donahue. Take, for example, ex-stockbroker "Matt Trenton. ' ' Work stifled him, his wife kicked him out, and at twenty-four he'd become an alcoholic. Then he woke up one morning with "a more sweeping remedy to his plight," writes Sedgwick: "There was a voice screaming at him from inside his head. . . yelling two words. . . over and over: 'Go sailing! Go sailing!'

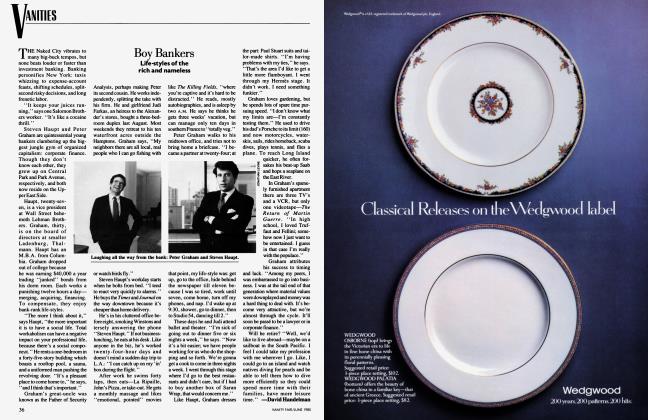

Why did these normally cagey, defensive heirs open up? Green-eyed, mild-mannered Sedgwick, thirty-one, explains while sipping coffee in his sunny row-house duplex.

"It was clear they were talking tooneoftheirown. " Like most Sedgwicks, he went to Groton and Harvard, and his family maintains a two-hundred-yearold mansion in the Bcrkshires, built by John's great-greatgreat-grandfather, the fifth speaker of the House of Representatives.

"They had a sympathetic listener, because 1 come from some money," Sedgwick says. "Not as much as they, but enough. I came across as being genuinely interested, with a very clear ulterior motive [i.e., the book]." He also ingratiated himself by offering to pick up the checks for meals. "I didn't want to make it seem I was freeloading. Most of the time they let me pay, because it was so rare for them."

He'd learned his interrogative skills from the subject of his first book. Night Vision, Boston private eye Gil Lewis. "Gil taught me how to listen to a mass murderer's confessions. The trick is to keep your eyes calm." So, during tales of bareback sexual congresson marble floors, "like a good psychiatrist," Sedgwick often found himself saying, "Mm-hmm, mm-hmm."

Though Rich Kids is more anecdotal than analytic, Sedgwick says he thinks a consistent theme emerges. "Money pushes you to extremes. In the case of generosity, it makes you really altruistic; in the case of minor nuttincss, it makes you a cataclysmic crackpot. With none of the normal constraints—answering to a boss, paying rent, even obeying laws—a lot of rich people just drift off into the ether. And, at the same time, you're a big sugar pile and all the ants come crawling. You spend a lot of time fending them off, clubbing them away. ' '

Sedgwick claims to have "mixed feelings" about wealth. "I'm a good Wasp; particularly in Boston, money is supposed to be hidden." But he also admits, "There's a lot to be said for the Grand Style. I like dash, confidence, being larger than life, and money can give you those. The pity is, instead of enlarging these rich kids, money beat them down."

His father, R. Minturn Sedgwick, aware of these destructive powers, kept John isolated from Edie's richer, wilder branch of the family. When Minturn died in 1976, John inherited $70,000, in $250-a-month doles, enough only to subsidize his writing career. "The hidden agenda of the book," he says, "was to come to terms with my own past and my own inheritance." Rich Kids seems ultimately a self-justification, affirming his father's method of endowment while depicting the traumas of being truly doughbound. Even those who devote their lives to charity are suspect, he writes: ' 'They attain a certain state of grace. And yet, living lives so removed from the gogetter capitalist mainstream, they are also a little. . .peculiar."

He later explains, "I don't think it's so much fun just to have it [money]. The pleasure is in earning it. That's the American way." Toward this end, Sedgwick has become a sort of armchair wealth watcher. His writing now includes a regular column on the social classes for Success! magazine.

"I delineate the ways the classes are different—mostly upper and middle, the only two that really count." Topics have included Ambition, How People Handle Bills, and The Idea of Harvard.

Sedgwick and his wife, Megan Marshall, have twin word processors (she's authoring a book about the Peabody sisters), and they stagger work schedules around their shared printer and eighteen-month-old daughter, Sara. This Sedgwick homestead has a cheerful, lived-in look, with baby toys strewn on the baby-grand piano. Today, Sedgwick's heading out for a game of basketball and a barbecue. "I'm just a regular guy," he says, and grins.

David Handelman

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now