Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTransAtlantic Ferri

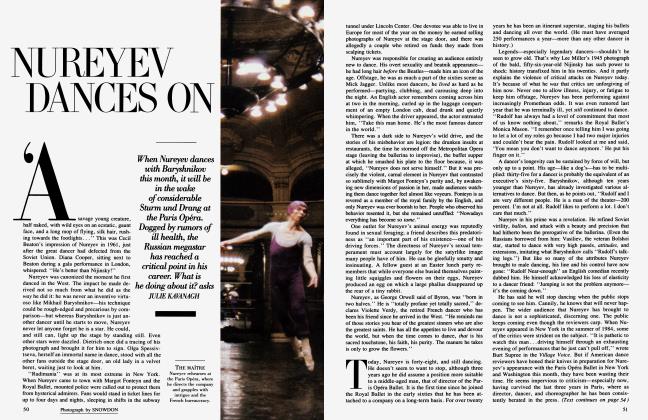

Julie Kavanagh

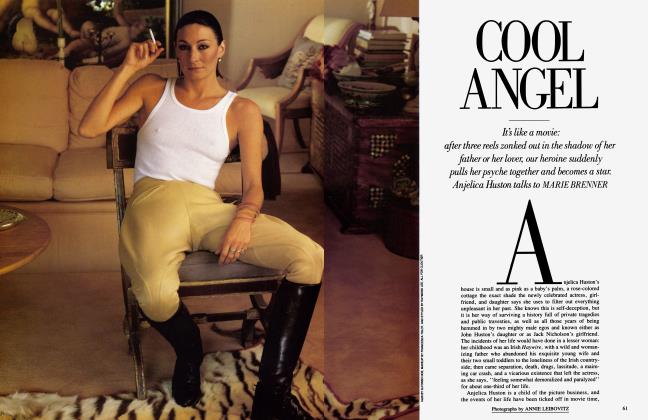

The most striking thing about Alessandra Ferri in the beginning—when she was seventeen and had just joined the corps of the Royal Ballet—was her extraordinary plasticity.

With sky-piercing arabesques and a back as supple as willow cane, she had a line so beautiful it would have made a choreographer out of a lumberjack. In 1982, when Ferri had been with the company for less than two years, she was cast as Mary Vetsera, the doomed mistress of Crown Prince Rudolf, in Kenneth MacMillan's Mayerling. And with her first performance in a principal role she became a star.

Last year MacMillan chose Ferri for the lead in the television version of his Romeo and Juliet, causing considerable pique among the Royal's senior ballerinas. But Ferri is young and Italian, and she was the earthy, modem Juliet that MacMillan wanted. His Romeo, created in 1965, had been inspired by Franco Zeffirelli's revolutionary production at the Old Vic in 1960, and Ferri shaped her performance after that of Olivia Hussey in Zeffirelli's film of the play. "Hers was the only Juliet I agreed with,'' Ferri says. Vivacious, sexually responsive, resourceful, willful—Fern's Juliet questions and fights back. "None of that would have happened to her if she'd been shy."

This month Ferri is performing Juliet for the first time in New York, and for the first time as a principal dancer with

American Ballet Theatre. Mikhail Baryshnikov, A.B.T.'s artistic director, invited her to join the company last February, on the night of her debut as Odette in Zeffirelli's production of Swan Lake at La Scala. "From my point of view, she's one of the few exciting dancers around," Baryshnikov says. "She has a dramatic sense that is natural and unforced." Ferri decided to leave the Royal Ballet, provisionally, for a season.

Ferri is MacMillan's protegee and the successor to Lynn Seymour as his muse, so when MacMillan went to New York last year to become A.B.T.'s artistic associate it was widely assumed that she would not be long in following him. Seymour was the prime inspiration for MacMillan's Juliet, both dramatically and choreographically. It was her body that shaped the dance: all those headlong dives and tumed-in retires were made in homage to her exquisitely expressive legs and feet. While physically very different from Seymour, Ferri has inherited the same slightly swaybacked legs and dramatic insteps that extend the arabesque line indefinitely by arching upward like a sickle blade. The steps made for Seyz mour twenty years ago seem S revivified every time Ferri per| forms the role.

Not unreasonably, Ferri reg sists the comparison to Sey^ mour, whom she never saw perform. "I'm not a second anyone, I'm me." But they both have been able to interpret MacMillan's wishes with uncanny intuition. "Lynn and I rarely spoke about what we were doing, and it's the same with Alex," he says. Although she has yet to develop Seymour's gift for playing with nuances within a phrase, Ferri is a remarkably musical dancer with a quality of enjambment to her phrasing that gives fluency and fervor to MacMillan's great dramatic duets. She seems fearless, never interrupting the musical impetus to anticipate a risky lift.

Ferri has the body of a gamine, yet with her black brows, flashing eyes, and Kinski-like lips there is a definite voluptuousness about her. Frederick Ashton recognized this Esmeralda quality when he cast her as the Gypsy girl in The Two Pigeons, and five of her roles in MacMillan's ballets present her as a temptress. (As Anna II in his television version of The Seven Deadly Sins she dances the sizzling "Lust" duet wearing stockings and suspenders.) But she also brings a childlike air to these roles; her seductiveness is offset with innocence. It is a combination that Zeffirelli prized when he worked with her in Milan. "I love those passionate Italian eyes that can suddenly open wide with purity." Fem danced Odette to Carla Fracci's Odile in Zeffirelli's controversial production of Swan Lake, the idea being to heighten the contrast between pure and profane love by having two ballerinas dance the lead. Her performance won her considerable acclaim and enormous admiration from Zeffirelli, who has become a friend. "She has the quality which for me is an alarm that goes ting! Talent at work here. I found it in Callas, Magnani, Hussey, Taylor. . .Each time I speak with her, I see the ghosts of all those ladies."

Ferri has been identified as a "MacMillan dancer," which in England means "unclassical," since his style distorts the academically pure, Fonteyn-derived English line, so she watched her young colleagues at the Royal cut their teeth on the classics while she wasn't given similar chances. Too late to prevent her from leaving, she was cast in the fourth act of La Bayadere in July, and even in early rehearsals was surprising herself with the ease with which she could tackle it. "I used to believe I couldn't do things, because everyone kept telling me that I lack technique."

One of her main reasons for going to A.B.T., she says, is to be thrown in front of an audience expecting technical tricks. Ferri feels she needs to be tougher and risk more. "Dancers in the Royal Ballet have become very complacent about technique—everyone is happy with just two pirouettes. I'm going because I'm not like that."

There are some who will say that Ferri is deserting a sinking ship. The Royal Ballet was criticized vehemently and unanimously this spring when a revival of Ballet Imperial mercilessly exposed the company's decline in standards. Her departure is a loss to them, but the chances are she will be back. In the meantime, Ferri's future looks rosy. After Romeo she will dance in a new ballet MacMillan is creating for her and Baryshnikov, and there is the prospect of Giselle in the spring.

"Time will tell how she will work out in the classics," says Baryshnikov. "Everything is in her hands." But as MacMillan notes optimistically, "Americans won't have seen anyone like her since Gelsey Kirkland."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now