Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowMOVIES

Wholehearted Hannah

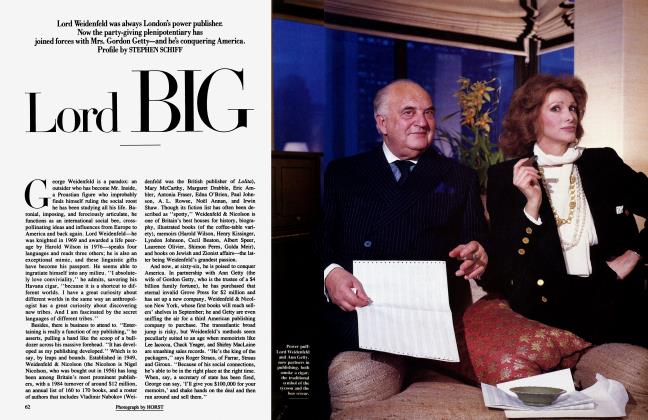

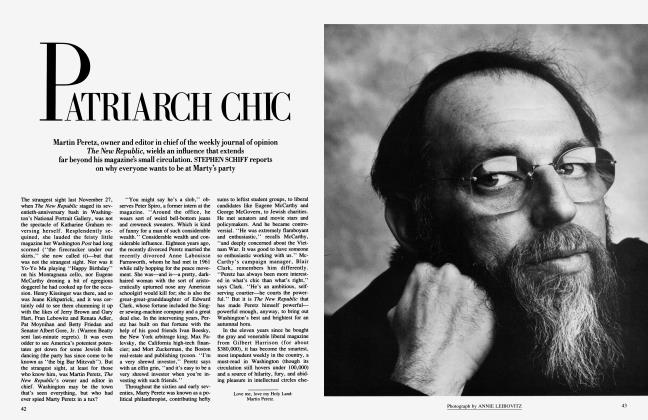

Stephen Schiff

The first laugh in Woody Allen's glorious new movie, Hannah and Her, Sisters, comes during the credits—and it's unintentional. There, in the usual somber white-on-black, is a name that always evokes somber shades of gray: Max von Sydow, the star of Bergman's sonorous dirges. Could this, I wondered, be Woody's ultimate paean to the master—his Wild Gooseberries? And what would von Sydow do in a Woody Allen movie? Play mah-jongg , with Death?

Actually, von Sydow plays Frederick, a terribly downtown artist whose elephantine penstes are squeezing the life out of his beautiful girlfriend, Lee (Barbara Hershey). Day after day, Frederick fogs the loft with pronouncements on the Holocaust and human suffering. There's not a simple, pleasure-loving bone in his body, and though Allen respects his broody sensitivity, he also recognizes that this guy is no romp around the punch bowl. So when Lee kisses him off, the movie does too— Allen seems to be saying good-bye to his Bergmanesque hankerings, and hence to the tortured Strindbergian tradition behind them. In fact, Hannah feels more like Chekhov: it's breezy, light-headed, poignant, and very, very funny. Allen has created a richly polyphonic comedy that proves its seriousness not by pondering the great imponderables but by letting its characters dance their private dances—and then by choreographing them so they jingle together like the shards of a mobile.

This is his best movie since Annie Hall, and part of what makes it hum is the setting. Allen's last several films have bogged down in never-never lands of the past—or, worse, in Jersey—and they've all felt strained, miniaturized, drab. But Hannah beams contemporary New Yorkness—the parties, the restaurants, the jitters—and if Allen has a tin ear for period dialogue, he can still conjure entire symphonies from Manhattan's clatter. The still center of the movie is an actress-tumed-housewife named Hannah (Mia Farrow), who is so perfect and sweet and beautiful and loving that she drives everyone crazy— her staid husband, Elliot (Michael Caine); her hypochondriac ex, Mickey (Allen); and her two sisters: Holly (Dianne Wiest), a lovable ne'er-dowell, and Lee, whose fervid affair with Elliot is the film's live wire, jangling the atmosphere and spitting sparks at passersby.

As the movie zigzags among the characters, it also layers mood upon mood; Hannah and Her Sisters is by turns tender, bitchy, exalted, and completely bananas. Instead of trying to make a single figure—the one he portrays—contain all his disparate humors, Allen sprinkles odd bits of his sensibility throughout the film. If Frederick's peeks into the abyss are dreadfully solemn, Mickey's are nuts, and the one never clashes with the other. Ripping apart his personality and examining the pieces one by one, Allen has achieved a kind of reintegration (it sounds awful to say this, but the years of psychoanalysis may have paid off). Hannah and Her Sisters is about people reassembling themselves, about healing, and when the ex-neurotic Mickey nuzzles his exneurotic new wife in the triumphant final scene, Allen gives off a grown-up sensuality we've never felt from him before. He's found a way to create warmth without meltdown.

But the movie isn't perfect. Despite its crisp visual sheen, there are stretches of clunky staging, and scenes in which people unaccountably disappear behind posts while they're talking to us. And there's something cheesy about the way Allen slings show-offy references around; in this movie, we get everything from Ibsen to Richard Yates, not to mention between-scene titles that quote Tolstoy. Yet the references no longer seem tacked on just to impress us, the way they sometimes did in Manhattan. Here they emerge from the characters, who are so fully realized that we instantly grasp what place a Bach concerto holds in their lives, or e. e. Cummings, or The Easter Parade. And most of the performances are splendid—Mia Farrow burrows deep under the skin of a woman whose talent and glowy contentment send lesser mortals into envious frenzies, and Dianne Wiest's Holly, who doses up on optimism the way she does on coffee and cocaine, should make her a star.

As for Allen, he's cast himself as a comedy writer whose cancer scare sends him questing for Answers. In the end, he finds peace much the way Joel McCrea did in Sullivan's Travels: he watches Duck Soup and, despite the Meaninglessness of it all, has a pretty good time. "I should stop ruining my life searching for answers I'm never gonna get," he decides. Which is precisely the sort of trendy, shrugging response that usually makes my blood boil; it smacks of the hip philistinism that lulls otherwise serious people into regarding any metaphysical inquiry as hopelessly pass6. Yet the rest of the movie belies that attitude; the comic tone has itself become searching and sage. ''Maybe comedy can sit at the grown-ups' table," Allen seems to be admitting. High time, too—the maturity this film radiates was plainly hard won. Indeed, if squirming through Interiors and all the other awkward experiments was the price we had to pay for Hannah and Her Sisters, it was worth it. Surely this is the movie of the year.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now