Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowLOW DEEDS ON THE HIGH SEAS

STEPHEN SCHIFF finds the fourth cinematic sailing of The Bounty fresh and vigorous

Film

THE last place anyone would have expected to find a penetrating study of British class and colonialism was in The Bounty, the fourth screen account of the familiar 1789 mutiny. But the new film is remarkably thoughtful and balanced. Directed by the Australian Roger Donaldson (whose first two features, Sleeping Dogs and Smash Palace, were made in New Zealand), The Bounty isn’t a rousing swashbuckler, for all its flashing swords and limpid seas and dusky lasses doing the bunga-wunga. It’s a stately, slightly poky film with an oddly menacing atmosphere; the usual tall-ship-against-flaming-sunset shots are tempered with charcoal streaks, and Vangelis’s electronic score is full of ominous booms and snaky, slithering noises—the sounds of something fearful approaching from a great distance. It’san ambiguous movie, with a fated, Wagnerian air. And its subject is the chemistry of Empire, the rise of the repressed—civilization and its murky discontents.

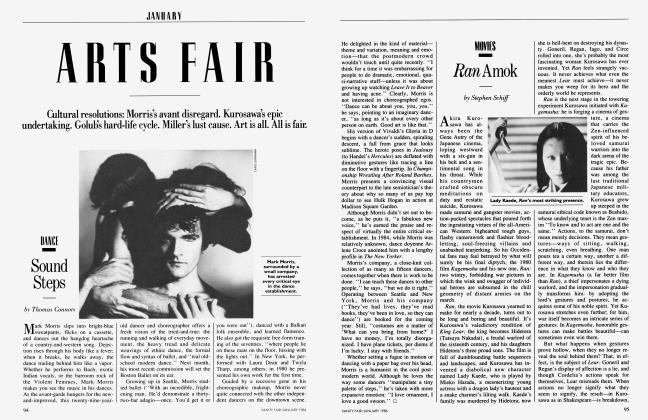

The 1935 (Clark GableCharles Laughton) and 1962 (Marlon Brando-Trevor Howard) versions of Mutiny on the Bounty were based on the famous Nordhoff and Hall book about how Fletcher Christian, second-in-command aboard a vessel charged with bringing breadfruit from Tahiti to Jamaica, wrested control of the Bounty from its fiendish commander, William Bligh, and set him adrift in the South Pacific. These were American films, and in their way they perfectly embodied American views of the British—as demons of repression, as antediluvian schoolmarms , or, in the case of Marlon Brando’s Christian, as epicene fops. The new movie, however, appears to be an English view. Robert Bolt wrote it (he also wrote Lawrence of Arabia and A Man for All Seasons), and you can feel the intensity of British self-examination burning beneath its surface. Based on Richard Hough’s factual study, Captain Bligh & Mr Christian, the story is set up less as a drama than as an investigation; it’s told in flashbacks from Bligh’s trial, and much of its strength lies in the way it topples expectations. We discover, for instance, that the blue-blooded Christian (Mel Gibson) and the middle-class Bligh (Anthony Hopkins) were good friends, and that, far from being the sadistic miscreant of legend, Bligh was a deft and reasonable sea officer, a center of reassuring calm on rough seas, an indulgent overseer during the crew’s raffish rituals (including a dangerous-looking drag show), and a sensitive diplomat on Tahiti, where the barebreasted welcoming parties and fertility rites shimmer before us like a Margaret Mead fever dream.

I was worried when I heard that the new Bligh was to be portrayed by Anthony Hopkins, because Hopkins can curl his lips and pop his eyes like a little Charles Laughton doll, and anyone who watched him in Magic or Audrey Rose has already seen everything that can be done with the human jowl. But Hopkins is a surprise. He sketches Bligh’s coarse nobility alongside his repression; you can see the way venom, envy, and rage roil his features and then sink beneath them, as if his pores were drinking them in. With his closecropped hair and his cowed eyes, Hopkins’s Bligh resembles a seething penitent. And one understands what makes him seethe whenever he’s around Mel Gibson’s Christian or the supercilious young officer Fryer (Daniel Day Lewis). It’s class jealousy. These seagoing playboys have none of the hardness and discipline Bligh has so carefully cultivated, but they don’t appear to need it, either. They’re beautiful and rich; they glow. When Bligh and Christian go ashore at Tahiti, Bligh squints at the maidens, the palm trees, the splendid crags beyond, and visibly tucks himself in. But Christian is agog; his expensive education has prepared him to embrace exotica in a way Bligh can’t. And as Christian succumbs to Tahiti ’ s sensuality, lolling about in grass huts with the king’s lissome daughter, even letting himself be ornately tattooed, we can see how the seeds of mutiny are sown. Their blossoming will not be so much an outcry against tyranny as a clash of values, a clash made inevitable by the jolting apprehension of another culture, another world.

The Bounty isn’t melodrama, but it isn’t a dry historical essay either—Donaldson’s direction is marvelously vigorous and detailed. There are two violent scenes—the mutiny and an episode among Tofuan islanders— which are so shocking that you forget how well you know the story. Donaldson captures the way brutality spirals out of edgy uncertainty; he gets at the crazy acceleration of anger and fear. And though Mel Gibson’s Fletcher Christian never quite gels, Donaldson brings out something mercurial and jumpy in Gibson, something no one has exposed before. During the mutiny, you can see Christian’s terror stoking his rage: he hates Bligh for forcing him to revolt and hates him even more for being dignified and tough, and for having been his friend. What we are watching isn’t a declaration of independence; it’sthe volatile alchemy of class and Empire at work.

The mutiny scene is so freshly observed that it seems a demonstration of principle. If one believed (as I did) that there was nothing left to say about the boring old Bounty, Donaldson proves that no legend is so hoary that its original vividness cannot be rediscovered. In the end, when Christian and his gang are left on the beach at Pitcairn Island, never to return to civilization, you may feel haunted by their fate in a completely new way. Donaldson has reawakened the Bounty story’s mythic vibrancy, and no myth is complete until the hero returns home—or, like Brando’s Christian, dies trying. It is a measure of the filmmakers’ rigor that they’ve left their tale so queasily unresolved: what Fletcher Christian has undergone has ruined him, as it ruined a great many colonials, who, having stumbled upon a world of balmy breezes and sensual voodoo, could never quite go home again. And yet he cannot erase, cannot repudiate what he has seen and felt. Like England itself, he longs for a past he has willingly destroyed —for reasons his countrymen are still fervidly struggling to grasp.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now