Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowRan Amok

MOVIES

Stephen Schiff

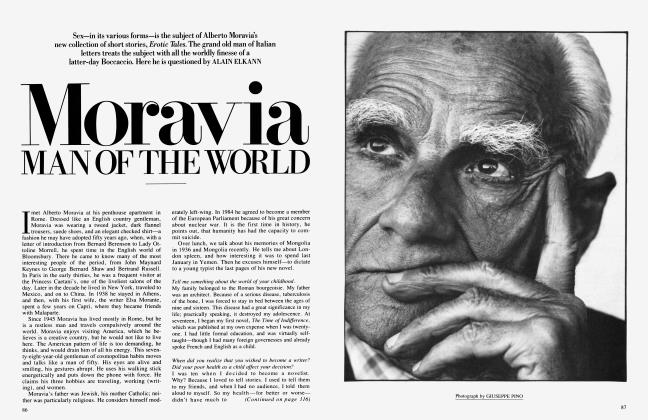

Akira Kurosawa has always been the Gene Autry of the Japanese cinema, loping westward with a six-gun in his belt and a sentimental song in his throat. While his countrymen crafted obscure meditations on duty and ecstatic suicide, Kurosawa made samurai and gangster movies, action-packed spectacles that poured forth the ingratiating virtues of the all-American Western: bighearted tough guys, flashy camerawork and flashier bloodletting, soul-freezing villains and unabashed tearjerking. So his Occidental fans may feel betrayed by what will surely be his final diptych, the 1980 film Kagemusha and his new one, Ran: two wintry, forbidding war pictures in which the wink and swagger of individual heroes are subsumed in the chill geometry of distant armies on the march.

Ran, the movie Kurosawa yearned to make for nearly a decade, turns out to be long and boring and beautiful. It's Kurosawa's valedictory rendition of King Lear; the king becomes Hidetora (Tatsuya Nakadai), a feudal warlord of the sixteenth century, and his daughters Hidetora's three proud sons. The film is full of dumbfounding battle sequences and landscapes, and Kurosawa has invented a diabolical new character named Lady Kaede, who is played by Mieko Harada, a mesmerizing young actress with a dragon lady's hauteur and a snake charmer's lilting walk. Kaede's family was murdered by Hidetora; now she is hell-bent on destroying his dynasty. Goneril, Regan, Iago, and Circe rolled into one, she's probably the most fascinating woman Kurosawa has ever invented. Yet Ran feels strangely vacuous. It never achieves what even the meanest Lear must achieve—it never makes you weep for its hero and the orderly world he represents.

Ran is the next stage in the towering experiment Kurosawa initiated with Kagemusha: he is forging a cinema of gesture, a cinema that carries the Zen-influenced spirit of his beloved samurai warriors into the dark arena of the tragic epic. Because his father was among the last traditional Japanese military educators, Kurosawa grew up steeped in the samurai ethical code known as Bushido, whose underlying tenet is the Zen maxim "To know and to act are one and the same." Actions, to the samurai, don't mean merely decisions. They mean gestures—ways of sitting, walking, scratching, even breathing. One man pours tea a certain way, another a different way, and therein lies the difference in what they know and who they are. In Kagemusha (a far better film than Ran), a thief impersonates a dying warlord, and the impersonation gradually transforms him: by adopting the lord's gestures and postures, he acquires some of his noble spirit. Yet Kurosawa stretches even further; for him, war itself becomes an intricate series of gestures. In Kagemusha, honorable gestures can make battles beautiful—can sometimes even win them.

But what happens when gestures prove hollow, when they no longer reveal the soul behind them? That, in effect, is the subject of Lear: Goneril and Regan's display of affection is a lie, and though Cordelia's actions speak for themselves, Lear misreads them. When actions no longer signify what they seem to signify, the result—in Kurosawa as in Shakespeare—is breakdown, disorder; in Japanese, the word ran means chaos. And for Kurosawa, chaos is the ultimate evil. Ran's smoky, exorbitant battle scenes are as magnificently staged as the ones in Kagemusha, but this time there is no glory in them; they're all blood and brimstone. As the troops course down muddy hillsides, their color-keyed flags flapping, thunderclouds signal them forward, turning the light now yellow, now brown, now an unearthly, gruesome purple; horses squeal and crumple; soldiers stare in Kabuki anguish at their own severed limbs. Kurosawa has shot these scenes from an icy remove, a gods'-eye view that admits no heroism. In Ran, war is a distant folly, awesome only in its squalor.

But here Kurosawa's usual mastery of narrative rhythm fails him. When we return from these plangent war sequences to his stark, staring Lear, the movie feels listless, even trivial. That's partly because as Hidetora becomes unhinged, so does Nakadai's acting; it gets shriekier by the second. Then, too, the Lear story seems ragged without Shakespeare's language. When the Fool (played by a human commotion known only as Peter) is reduced to lines like "Man is born crying; when he cries enough, he dies," we might as well be reading T-shirts.

And there's another, larger flaw. Despite appearances, Ran isn't about chaos at all. It's really about a woman's revenge. Lady Kaede's arsenal of threats, seductions, and poison pouts makes Lady Macbeth look like a sulky cheerleader, and whenever she's weaving her immaculate deceptions, Ran suddenly whirs and shimmies. In stories of grand deceits, the deceiver is bound to be more intriguing than the victims. So Kurosawa has bamboozled himself: the moral universe Kaede inhabits is far more sophisticated than anything else in the film. After all, we in this century have learned to recognize that chaos, however grim, is not the ultimate evil. Order can be more monstrous still. By adding Kaede's perfectly calculated schemes, Kurosawa has upset Shakespeare's delicate balance. He's doomed his Lear to be a supporting player, less a fallen king than a pawn in the dark queen's game.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now